Moral Panics and Music Journalism

Kyle Bylin (@kbylin), Associate Editor

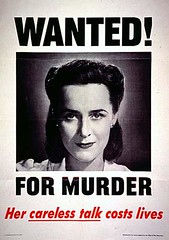

I am not a murderer. Therefore, to be accused of such an atrocity does elicit a certain degree of animosity within me. Yet, Nathan Harden has done just that.

In an essay that recently appeared on The Huffington Post titled The Generation That Killed Rock 'n Roll, he outright blames my entire generation for the killing of rock 'n' roll. First, let us take into consideration exactly what Mr. Harden has done here, intentionally or not.

With the wording of his title, he evokes moral panic and folk devils. In case you’re not familiar, a moral panic is a false appeal. It is when a group of persons has been in recent times been defined as a "threat to societal values and interests."1 Those blamed for posing such imminent threats on society are called folk devils.

In Moral Panics and the Copyright Wars, William Patry writes, “Conjuring up moral panics and folk devils occurs through metaphors casting the other side in an unfavorable light, in the case of copyright, by painting those who use works without permission as thieves, trespassers, pirates, or parasites.”

Thanks to Mr. Harden, we can now comfortably add murderer to the list.

To be sure, in the titling of his essay, what he’s doing there is not simply using words to make a provocative title, but to frame the discussion in your mind.

He’s blatantly using moral panics, folk devils, and metaphors as tactical weapons that are designed to cast Digital Natives in a negative light and as a threat to something of societal value and interest, like rock 'n' roll. In effect, what he has attempted to position, and quite falsely, is the notion that Digital Natives should associated with and thought of as “murders” that “killed” rock 'n' roll.

Now, why might Mr. Harden choose such powerful metaphors?

Patry explains, “[The] use of metaphors in the Copyright Wars is almost entirely negative, the result of calculated political strategies to psychologically demonize opponents to make them appear to be bad people. Because these bad people are doing bad things, they must be punished the way bad people are: by being sued, by paying exorbitant damages, and in some cases by going to jail.”

Hence, murder he implies, for that very reason, because of how effectively it taps into our emotions and not our instincts. Murderers are bad people.

He, of course, explains himself further in the comment section by saying that he does not mean to imply the death of the genre, but of “global rock brands like the Stones or U2.” Going onto say that, “If all we have twenty years from now are regional indie acts – no one capable of selling out the Rose Bowl two nights in a row — we do lose something. The fact that music will carry on is a given. But will you and I be able to share, from across the country, a common musical culture?”

In the words of author and American urban studies theorist Richard Florida, “Not so fast.” With regards to Michael Jackson’s passing and many news outlets proposing the end of celebrity in our culture, he had this to say:

There’s good reason to suspect that, sooner or later, new technology will spawn an even bigger mega-star with even more global reach. That’s been the pattern in the past actually and there’s little reason to think it will end now… With every new technology – from the rise of film, recorded music, talking pictures, transistor radios, FM radio, cable TV, and now the digital revolution – experts have predicted the death of celebrity. But each advance has generated celebrities bigger than the past. New technologies, as the work of German economist Peter Tschmuck has shown, open up new distribution channels and new markets that give birth to ever bigger stars.

Florida’s hunch is that, “we will see a new mega-star on a truly global scale. Not arising in one country like Elvis from the U.S., or the Beatles coming from the U.K. to “invade” America, or Jackson, an American conquering the world. This will be a celebrity who emerges simultaneously on a global scale – a person less tied to one country of origin who will be seen from the outset as a world mega-star.” So, it’s possible to say that one day we may see a rock band that also emerges on a truly global scale and as Andrew Dubber likes to point out, who’s to say that they or anybody else, won’t have the highest selling record of all time too.

But, could they sell out the Rose Bowl two nights in a row?

It’s entirely possible. But, whether or not this “global rock brand” could sell out this venue doesn’t seem to serve as an accurate model of success that we should use to determine how valuable someone’s art has been to society. Nor does what Mr. Harden proposes, address, in any meaningful way, the numerous and more complex issues at hand other than just file-sharing. No doubt these have been some difficult times for most, but they’ve also brought forth many fantastic things that he simply chooses not to mention in his rather pessimistic view of the record and music industries.

However, I refuse to accept the badge of a murderer. I was thirteen once and I’m well aware that what was considered revolutionary then has since become a commonplace fixture in our culture. That file-sharing has had a negative effect on the record industry isn’t a secret nor is it a myth. But, exclaiming outright that this population of Digital Natives ought to be looked at as morally bankrupt murderers who — through their everyday interaction with technology and culture — should be held accountable for killing the very music that they love doesn’t sit right with me.

Not simply for the reason that I was once a part of those in question either, but because such accusations don’t move the conversation forward. They don’t seek an understanding fueled by imagination and curiosity, but that of a pinhole perspective. Nowhere in Mr. Harden’s essay does he attempt to speak of the rise of the networked audience, the fall of mass marketing, the fracturing of the media landscape into niches, the end of the format replacement cycle, the explosion of alternate and immersive entertainment options, the converging of top-down corporate media and bottom-up participatory culture, or even the evolution of social music.

Why? Maybe, because none of these are sound bite explanations that can be easily packaged and shipped off as catchy headlines that can make their way to Digg. As to whether or not we will continue to share a “common musical culture,” I have asked myself this same question. Except, after having thought about this for quite some time, what I came to realize is that music will always be the sociocultural superglue of the masses. But, with one big difference: that we will no longer be the masses at all. Instead, going forward and for a several years now, we have been a networked audience and have indeed shared a common musical culture.

There happens to be more issues that I have with his thoughts than I want to brother wrapping my head around at the moment. Not for the reason that I can’t argue against them properly, but because I’ve come to conclusion that from reading this blog a large number of you probably don’t need me to spell it out for you. As so many of the topics that he brings up happen to be of the things that I naively thought weren’t points people bothered to argue anymore.

What’s important though is that we shouldn’t oversimplify the causes of these complex events nor focus solely on one cause while ignoring the other factors that are engaged in this process, because doing so only serves to stupefy the general public's understanding more than it enlightens.

Plus, Mike over at TechDirt has already done a great job at debunking this.

I’m so tired of baby boomers. We are all servants to the Jay Leno ruling class.

you fuckin hippies

bbb

wheatus.com

File sharing, combined with social networking, could still be the best thing that ever happened to rock and roll, if it were only legal.

Music used to have to filter up to a label, then back thru press, radio, and retail, before anyone heard it. Even if you got signed, even if millions were spent promoting an act, there were limited channels of exposure. IF someone heard you on the radio, IF they read about you in a magazine, IF they saw you live, then MAYBE they’d find your record in a store, and there was a chance they’d buy it.

File sharing removes all those obstacles, and becomes a staggeringly powerful distribution method once it comes out of the shadows, particularly in the context of social networking. All the people reliving memories on Facebook could be doing so with a soundtrack, if it were legal.

Take the 1999 Napster, layer it into Facebook for $10 a month, and you’ve saved rock and roll.

Paul Begala wrote an excellent essay about the Baby Boomers: The Worst Generation. http://www.superseventies.com/worstgen.html

Who cares if there won’t be another Stones to fill the Rose Bowl. Miley Cyrus, or the Jonas Brothers will fill that gap because Disney is even better than the Stones at playing the monetizing/merchandising game. Andrew Loog Oldham describes the Stones playing a very hostile Dallas TX in 1966 and then recounts how amazing it is that just 11 years later, the Sex Pistols received an even more hostile reception in the same city. Rose Bowl status is not a mark of relevance, but of irrelevance.

This particular controversy tends to always end up rather heated. I do not subscride to the idea that the rock n roll is dead, however, I am willing to hear the argument as part of a conversation. I personally tend to agree with all of the points in this post. It is obviously scary to some, to have the metophorical rug be pulled out from under the music industry as we knew it. I hear a lot of complaining from musicians and music industry professionals alike about not being able to make any money in this industry anymore. Is it though…? Was it so easy in the old model? I mean you had to first get noticed and then picked up by a major record label if you wanted to have a shot at it. The odds of that happening (no matter how good your music was) weren’t in your favor. But even if you were fortunate enough to get the record deal. What if the label never released your album? What if they did and it didn’t reach the right ears and nobody bought it?

Basically, it is my opinion that, whatever the troubles of today’s music industry, there are far more opportunities to reach a niche market that will appreciate and support your music career. Thus giving musicians the possibility of being able to make a living in music. Yeah you have to do it yourself to a much higher degree. But what profession do you not need to become an expert in in order to make a living?

Sorry to rant.

Tom Siegel

http://www.indieleap.com

Does anyone else find it more than a little depressing that 99% of the actual music journalism since 2008 has come from tech blogs?