Big Tech Files Mass NOIs To Avoid Paying Statutory Royalties In Latest Artist Relations Debacle [Chris Castle]

In an ongoing saga of failures to ingratiate themselves with music business creatives, it seem big tech companies such as Google have recently been exploiting a loophole in the Copyright Act relating to compulsory licenses in order to avoid paying proper royalties to songwriters, writes Chris Castle.

__________________________

Guest Post by Chris Castle on Music Tech Solutions

As we saw in parts 1 and 2 of this post, New Boss companies like Google are playing on a loophole in the Copyright Act’s compulsory license for songs to shirk responsibility for song licensing from the songwriters or other copyright owners, get out of paying royalties and stop songwriters from auditing.

Not only have Google targeted long tail titles, but also new releases and songs by ex-US songwriters who are protected by international treaties. This is exactly the kind of rent seeking behavior by crony capitalists that gives Big Tech a bad name in the music community.

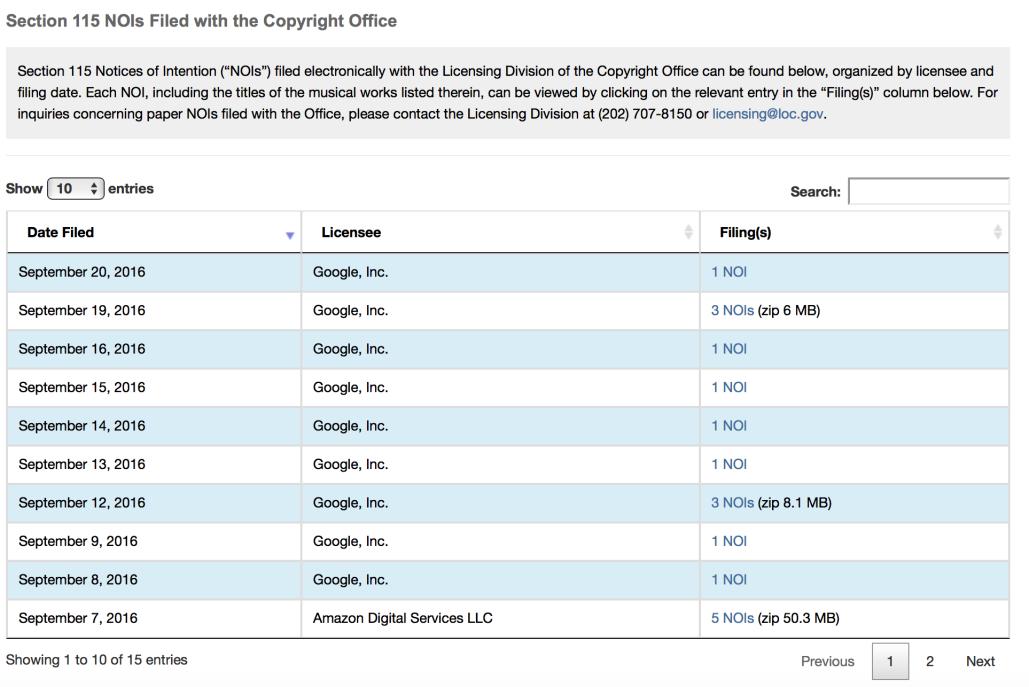

Google are doing this on a grand scale and at great expense, reportedly using “millions” of “address unknown” NOI filings with the Copyright Office that are supposed to be reserved for bona fide situations where the copyright owner cannot be found after a reasonably diligent search. Amazon is doing the same.

Through a quirk in the law (which needs to be fixed pronto) Google and Amazon are paying astonishing sums in filing fees to send the “address unknown” NOIs to the Copyright Office for songs that have not been registered for U.S. copyright or otherwise recorded with the Copyright Office. “Address unknown” NOIs are intended to be used when you really can’t find the address of the copyright owner after a diligent search of relevant records, although the Copyright Act limits the search to the public records of the Copyright Office. That limitation on records to be searched is a legacy echo from the 1909 revision of the Copyright Act which required registration and renewal for copyright to attach in the U.S.

So far, the overwhelming majority of “address unknown” NOIs are filed by Google. Spot checking the Amazon filings shows that Amazon filed a handful of titles.

Google apparently accomplishes this by manipulating a data dump from the Library of Congress that was never designed for filing mass NOIs and comparing the metadata in the data dump song title to their own list of sound recording titles that they want to exploit on their services.

Moral Hazard Revisited, DMCA Style

If you have a recording you want to use, you need to clear the song. You take that song title from the recording and look it up in the Library of Congress data dump. If it’s not there, you file the “address unknown” NOI. Wash, rinse, repeat 1,000,000 times or more. See how that works?

As if by magic, you don’t have to pay mechanical royalties until the songwriter figures out what you have done by checking the NOI submissions page at the Copyright Office (assuming anyone knows it’s there or knows their song might be listed) and then…does what?

Note that “1 NOI” means “1 NOI with tens of thousands of songs attached in an Excel file”

Note that “1 NOI” means “1 NOI with tens of thousands of songs attached in an Excel file”

This approach is fraught with moral hazard for largely the same reasons that plague the DMCA safe harbor–the party who benefits from avoiding both royalties and copyright infringement liability by sending the “address unknown” NOI is also the party who decides whether they qualify for the “address unknown” NOI. The Copyright Office clearly lacks the resources to cross check. Sounds kind of like DMCA notices, right?

The excuse the services give for this approach is that they can’t find the copyright owner for “long tail” and new releases.

The long tail part you can understand, but of course you have to ask yourself if a title is so obscure that you can’t find the song copyright owner, then why use it at all? Holding a track off of a service is far more likely to get the songwriter to come forward than sneaking around through the back door.

The New Release Scam Illustrated

It’s with new releases that Google runs the true arbitrage play. This is the part that makes no sense, particularly for songs written or owned by people with whom Google does repeat business. By relying on the “address unknown” NOI filings for new releases, even for songs that may be subject to a direct license, Google is using a loophole to appropriate value to themselves that should rightly go to the songwriters.

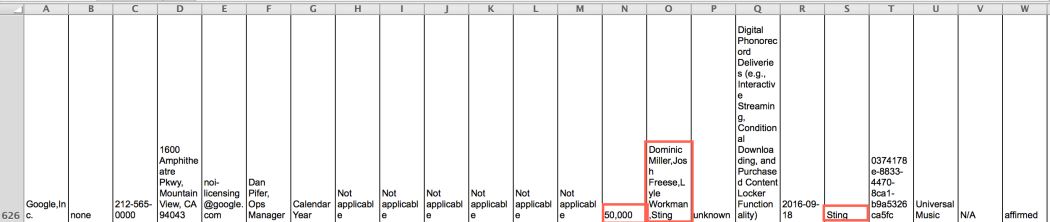

Let’s take another Sting example.

Sting released the song “50,000”, apparently as a single from his new 57th & 9thLP. “50,000” is an introspective Sting-style tribute to David Bowie and Prince. The album release date was September 23, 2016 and the single debuted around September 17. Google must have gotten the track around the same time as it is listed in Google’s September 16, 2016 mass NOI filing on line 626.

“50,000” is a particularly good example of how bogus Google’s approach is to “address unknown” NOIs. Google’s basis for filing the NOI on “50,000” apparently is that “50,000” is not included in either a copyright registration or other recording in the public records of the Copyright Office at the moment that Google looked for it. What this evidently means is that “50,000” wasn’t in the Library of Congress data dump sometime prior to September 16 when Google filed its mass NOI.

It is important to remember that there is no requirement for anyone to register their works or otherwise record their works in order to enjoy the rights of a copyright owner–such as mechanical royalties. This is true under international copyright law, not just in the U.S., so this quirk in U.S. copyright law is probably illegal and possibly unenforceable (which is why the “address unknown” NOI filing needs to be amended or eliminated–more about that below).

So simply put–how can you take away rights from a copyright owner based on a registration requirement that the copyright owner is not required to comply with because it is a formality that is actually prohibited by law? Sound Kafka-esque to you? It does to me.

In Sting’s case, Google knows who Sting is. They have other songs by Sting for which they probably sent an NOI. They may even have a direct license with Sting’s publisher that may actually supersede or be in lieu of a statutory license. In other words–they very well may have actual knowledge of Sting’s publisher. Wouldn’t that be a good place to start?

Yet because a new release has not yet shown up in the Copyright Office records, Google sends an NOI and will not be required to pay royalties until–if ever–the song is included in the Library of Congress data dump. Even though Sting is not required to register the song, Sting’s publisher may decide to register the copyright in order to take advantage of statutory damages and attorneys fees for infringement actions.

Getting a conformed copy of a copyright registration can take months–so for a single or an album, any mechanical royalties from Google under a statutory license during the new release window will never be paid. And if any direct license does not expressly prohibit including titles in mass NOIs, there’s a good chance no new release will get mechanical royalties from Google.

What Is To Be Done?

So now we know what the problem is, how to stop it? Not so easy to do.

1. Anticompetitive: It should not be lost on anyone that the government has created an opportunity for companies with market power to use their leverage to the disadvantage of their competitors as well as songwriters. It takes considerable capital to pay the filing fees to the Copyright Office and purchase data from the Library of Congress in order to arbitrage this loophole.

2. Take Down the Recordings: There are any one of a number of ways that the terms of a typical interactive music service license can be interpreted to allow the sound recording owner to pull recordings by at least current roster artists, especially new releases written by artist/songwriters (including co-writes) who complain to their labels.

3. Take Down the Songs: Direct licenses from music publishers presumably have some clause that will allow the publishers to stop mass NOI filings for their catalog, particularly of the type that creates a nonexistent distinction between versions of a song that have been retititled–not by the songwriter or publisher but by the artist or record company because the versions of the recording are different even though the song remains the same.

4. Counterfeits or Bootlegs (including stream rips): Statutory licenses are only available for sound recordings distributed under the authority of the copyright owner. There are a number of NOIs that look suspiciously like bootlegs or counterfeits, some of which may have been stream ripped. As Google is presumably sending NOIs for YouTube Red or other on-demand service.

5. Congressional Investigation to Stop the Library of Congress Selling Data for NOIs: The LOC has no business selling what is obviously incomplete data or misleading data to a user who so obviously is using it for a harmful purpose. The LOC could stop that immediately if they were so instructed by the Congress, and in any event the Congress should investigate.

6. Use Webform to Update or File Your Address Including Excel File Link: The Copyright Office has a webform for email contact by the public available here. You can use this to file your address and link to your catalog in an Excel file (hosted on your website or blog). Such correspondence is likely subject to FOIA (and therefore part of the public records of the Copyright Office), but you can also state in your webform that you are submitting the information with the intention that it become public and demand that your information be provided to anyone submitting a mass NOI as part of the LOC data dump.

The point that seems to have escaped Google and Amazon is that this loophole will surely be stopped, but what won’t be stopped is the complete lack of moral compass that would drive megacorporations to run roughshod over songwriters that they so aptly demonstrate.