Where Did All the Halloween Music Go? 🎃

What is the relationship of music to Halloween, and why don’t we have an established oeuvre of Halloween music like at Christmas?

Why Is Halloween Music So Much Harder to Find Than Christmas Music?

By Ian Temple of Soundfly Weekly

When an established artist wants to make a quick buck, they release a holiday album. Mariah Carey, Ariana Grande, John Legend, Justin Bieber, Frank Sinatra — I bet you can think of 10 others without much effort.

Actually, they do it even without the money. Snoop Dogg has a Christmas album (Christmas in Tha Dogg House). Masked hip-hop legend MF Doom has a Christmas mixtape. Prog rockers Jethro Tull and hair metal crossdressers Twisted Sister. Enya, Chris Cornell, Sting, Steve Winwood, the Ramones, and DMX have all thrown their hat in the ring. Reclusive indie artist Sufjan Stevens is practically the modern day Bing Crosby, with more than 100 Christmas songs. I just stumbled upon a chiptune holiday album called 8-bit Jesus by Doctor Octoroc.

Basically, Christmas albums are the potluck dinners of music. Everyone’s expected to bring a dish, and it’s impossible to have too many. I’ve got a friend who plays no instrument, has never made music before, and yet produces an annual Christmas album with his brother. My favorite carol of theirs is called “Here Comes Manta Ray” about a destructive sea monster that burns down your village and salts the earth on Christmas night.

Given all that, you’d think that the 2nd biggest holiday of the year might have a similar thing going on, but no. Where is all the Halloween music?

If you’re first reaction is “What about the Monster Mash?” you’re making my point for me. When it comes to Christmas music, I can easily rattle off about 50+ Holiday classics without much thought. The oeuvre is towering. When it comes to Halloween, the first thing that pops to mind is a gimmick, a 1962 novelty song by an out-of-work actor recorded alongside the sound of someone blowing bubbles with a straw.

Americans are traditionally very good at finding ways to make money. If there were money to be made on Halloween music, they’d have done it. So why is Halloween music not really a thing, beyond a few obvious exceptions?

Here are a couple theories:

Theory #1: Halloween’s history is much more fragmented than that of Christmas.

Halloween evolved from an amalgam of traditions, most famously the Celtic harvest festival of samhain that was practiced across much of Ireland and Britain before the large scale conversion to Catholicism in the 8th Century C.E. The Celts believed that the last day of October was a transitional time, and that after sundown the barrier between the world and the afterlife was at its thinnest. People dressed up to keep spirits at bay, held a big bonfire, feasted, offered tribute to their druidic spiritual leaders, played sports and games, sought predictions and romance, re-kindled their hearth fires, and otherwise partied it up.

It feels obvious that there would have been music at samhain — whether chanting, singing, drumming, etc. — but whatever it was hasn’t survived. The best we have are modern interpretations of what people imagined it might have sounded like, usually based on Celtic folk traditions: Modal folk tunes about dead spirits. Check out Lisa Thiel’s “Samhain” or druid artist Damn the Bard’s track “The Cauldron Born” for example.

By the 8th Century, Catholicism had moved in, usurping and absorbing the older festivals, and by the 13th Century, Catholics observed a three day celebration for the dead called Hallowtide encompassing All Hallows’ Eve (Oct 31), All Saints’ Day (Nov 1), and All Souls’ Day (Nov 2). In Ireland and Scotland, All Hallows Eve still retained some of the games and costumes and superstitions of samhain, just in a more christianized form, while the other days involved mass and prayers for the souls of the dead.

Another tradition started around this time was called “going a-souling,” where children would go door to door asking for treats. People were expected to give to the needy on Catholic holidays, and this was basically an extension of that.

And so the music of Halloween evolved from chanting around a bonfire to requiems for the dead sung at mass. Mozart’s famous “Requiem in D Minor” wasn’t written for All Souls Day, but it is frequently performed then. There’s a way in which this is the original Halloween music, and I’m here for it. It’s dramatic, morbid, epic, gothic, and calls forth the darkness. Imagine listening in a towering gothic cathedral, bats in the rafters, demons beneath the floorboards. It fits the bill.

Hallowtide did not survive the Protestant Reformation, and the puritans who founded the American Colonies forbade its practice, at least in the Northern Colonies. Ironically, there were no Halloween celebrations allowed in colonial New England, despite all the witches they had.

That all started to change in the mid-19th Century when more Catholics and Irish immigrated to the US and brought their celebrations with them, including parties, costumes, pranks, and a legend about a guy named Stingy Jack who tricked the Devil and was thus condemned to wander the world with nothing but a lantern in a carved out turnip. And that’s why we still carve Jack O’Turnips to this day.

Halloween began to take on more of its modern form in the US at the end of the 19th Century and into the 20th, especially among immigrant communities. At first, it was a night of mischief, ghost stories, and autumnal parties — but one not uniformly celebrated across the country. Vandalism was a big part of it. Apparently, people loved leaving smoking cabbage stalks in doorways or letting livestock out, and some places considered banning it.

Read more: Get a new musical essay delivered to your inbox every Friday when you subscribe to Soundfly Weekly on Substack.

Over time, it gradually became more of a civic gathering, as civic leaders tried to stem the violence and companies saw an opportunity. In the ‘20s and ‘30s, companies started producing black cats and witches for window displays, and towns started hosting parades and costume contests. Denison’s Bogie Book offered you everything you need to learn about decorating and hosting a Halloween event.

With the growth of the suburbs in the ‘50s, the pop-culture idea of Halloween started to take off, and trick-or-treating in purchased costumes became the norm. Slowly but surely, it evolved closer to where we are today: A de-centralized celebration focused on local gatherings that offer a slightly bombastic mix of traditions, from Celtic bobbing for apples to Catholic “souling” (trick-or-treating) to American sexy Darth Vader costumes.

Through it all, there wasn’t ever really a clear mainstream musical tradition to accompany it. When “Monster Mash” hit number 1 in 1962, people might have thought that was about to change — but it didn’t. Not even with Bobby Pickett’s slightly desperate-sounding follow up tune “Werewolf Watusi.”

Christmas, on the other hand, has a much more stable musical history. Christmas hymns date back to the 4th Century C.E.. And whereas the Protestant Reformation killed many Halloween celebrations, it supercharged Christmas music, encouraging the development of more secular carols and bringing the music into taverns and homes. The Victorians developed this further, and the Tin Pan Alley songwriters of the early 20th Century went nuts with it. Christmas music was codified every step of the way, and each new era layered seamlessly on top of the previous one.

Halloween as a holiday, on the other hand, has developed ad-hoc, and never had the linear, canonical curation Christmas has had. As author Nicholas Rogers puts it:

“As a holiday without an official patron, Halloween has never been securely anchored in national narratives. It has always operated on the margins of mainstream commemorative practices, retaining some of the topsy-turvy features of early modern festivals—parody, transgression, catharsis, the bodily excesses of the carnivalesque—and recharging them in new social and political contexts. That is part of the secret of its resilience and vibrancy.”

— Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night

Theory #2: Halloween lives more on film than in song.

Despite its lack of popular tunes, Halloween does have a popular cultural canon: horror films. That’s probably why much of the most recognizable Halloween music is actually film score music.

The Victorians loved ghost stories, stuff like Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the invention of movie making at the end of the 19th Century offered the perfect excuse for artists to experiment with putting those ghosts on film. Almost as soon as film was invented, artists were using it for horror, such as the pioneering filmmaker George Méliès’s “Le Manoir du Diable” from 1896:

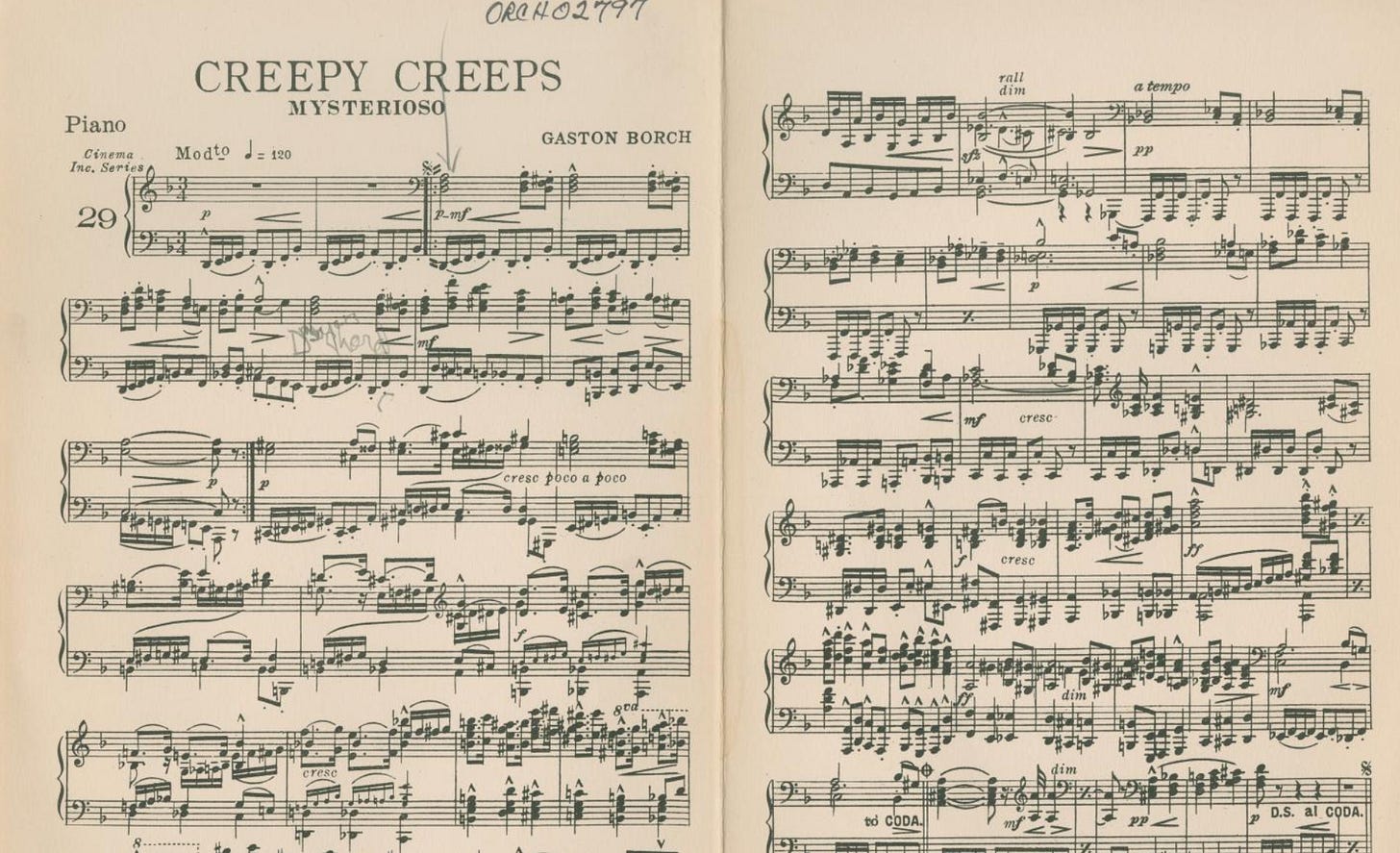

This silent film would have had live music performed to it, probably a collection of minor scale motifs and diminished chords, like this:

During the Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1930s, the studios were churning out films, and looking for stories wherever they could find them. It’s no surprise that Dracula and Frankenstein and the Wolf Man other monsters got swept up in it.

Over time film makers moved on from the cheesiness of monsters into psychological thrillers, like Hitchcock’s Psycho, and in the ‘70s and especially ‘80s toward the slasher and zombie flics of today.

But these horror films initially weren’t necessarily associated with Halloween. The early monster films and thrillers were an all year round thing. It seems to be a combination of a few factors that helped associate horror films with Halloween:

- The existing relationship between death / ghosts and samhain / Hallowtide / Halloween sets the table.

- When TV ownership took off in the 1950s (around the same time neighborhood trick-or-treating became popular), TV stations in need of content started broadcasting old horror films around Halloween, sometimes called “Creature Features” or “Shock Features.”

- In the 1970s and 1980s, the success of the movie Halloween and the subsequent slashers (Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, etc.) permanently tied the genre to Halloween, as studios began planning horror releases around this time of year. It may also be why Halloween permanently has a bit of an ‘80s feel to it, and the best Halloween music is arguably ‘80s soundtracks.

Because so many Halloween themes are brought to life on film, the music we most associate with Halloween is often film scores. When you enter a Haunted House, the most likely soundtrack will be horror movie themes, like John Carpenter’s self-composed theme for the film Halloween or the shrieking violins of Bernard Hermann’s score to Psycho.

While Halloween the holiday doesn’t really have a clear liturgy to it, there is a canonical “vibe” to it — the darkness, spookiness, mischief, fear, drama, witchcraft, etc. — and the best music for developing a vibe like that is film score music.

Theory #3: Halloween musical tropes don’t lend themselves very well to popular music.

The history is interesting, but I’m arguably over-thinking this.

Halloween music isn’t a thing because lots of the musical motifs we associate with Halloween are vaguely comical and don’t work very well with pop music. Big diminished chords. Saw orchestras and wailing violins. Dramatic dissonance. It’s all either too cartoonish or too intense and uncomfortable to fit easily with pop music.

Christmas-y musical motifs, like jazzy chords, uplifting choirs, and crooner voices, make you want to come together, hold hands, and sing over a crackling hearth. They emphasize warmth, comfort, and togetherness. Halloween musical motifs make you either roll your eyes or coil up all tense like a snake on the defensive. This is music for gouging your eyes out. Which would you choose? People might simply not want to binge music that makes them feel scared and alone.

Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” is the exception that proves the rule. It’s full of cinematic Halloween-y cheesiness, from the wolf howls to famed horror villain Vincent Price’s cackle at the end. And yet, it’s also one of the most successful pop songs of all-time, proving that it is possible to have a Halloween hit.

To be fair, it was not initially meant to be a spooky song — it started as an upbeat dance tune called “Starlight.” You can hear it in the main hook, which has very little of the horror trope about it (try replacing the line “thriller” with “starlight” and it’s a totally different vibe). The Halloween-ish elements are mostly ornamentation and layering, like the intro, the gothic-sounding organ, and the creepy theremin-sounding synth. The zombie dance music video definitely helped. If you want a Halloween hit, it helps to put it to film.

But there aren’t a lot of tracks that were able to replicate that. For an example of an artist that fell flat on their face in the attempt, enjoy Aqua’s 1998 jam “Halloween.”

That’s not to say there aren’t other great pop songs that fit well on a Halloween playlist — but most of them weren’t written for Halloween specifically. There’s Rockwell’s paranoid “Somebody’s Watching Me,” for example (with a cheat code: Michael Jackson singing the chorus). It was released in January, but has become a staple of the horror-pop genre at this time of year.

Someone else I asked mentioned Blue Öyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear the Reaper” — another one not written for Halloween specifically, but that tends to spike in terms of streaming numbers around now. I don’t think I’ve ever thought of it as a Halloween song before, but it makes sense.

Basically, songs with any sort of creepy lyrical element in a minor key and a dance-y beat are fair game a Halloween party. ‘80s vibes fit particularly well, I’d argue. But unlike Christmas songs, most of these songs can also be listened to at other parts of the year without it being weird.

Because of that, the lists of what comprises this sort of Halloween music are still very much in flux. The Halloween Party playlists on Spotify and Apple Music share the same first five songs, most of which we’ve already discussed, but after that differ fairly broadly. Spotify has Taylor Swift, “Phantom of the Opera,” and “Total Eclipse of the Heart” (?) while Apple Music has “I Want Candy” and Rob Zombie. The connections to Halloween are fairly loose on some of these, to be honest, although I’m not mad about it.

If wails, dissonance, and horror stabs don’t make for great pop music, it makes sense that the best music to listen to at Halloween parties doesn’t have any of that stuff. We can always pretend, especially if the lyrics mention monsters or something.

Theory #4: Halloween is actually great for music.

One reason there’s no established canon for Halloween is because as much as its a commercial holiday with candy and costumes, Halloween is also a time for celebrating the non-mainstream, for transgression and weirdness, for liminality and embracing the margins. It wouldn’t really make sense to have a monocultural musical tradition around it. It’s no coincidence that the main characters in horror movies are often misfits or nerds, like the kids in Stranger Things.

But that’s also the reason that many musicians love Halloween. Musicians have always loved to occupy and explore the spaces on the margins.

There’s actually a ton of great Halloween music out there in subcultures for whom its relationship to Halloween is only tangentially related to its importance, even though it does get played a lot at this time of year. Bauhaus’ “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” about the actor who starred as Dracula arguably spawned the goth rock genre in 1979. The industrial rock band Ministry has a song called “(Every Day Is) Halloween” from 1985 that’s popular enough 40 years later that the band just put out a music video for it this year. The lyrics are:

Well, I live with snakes and lizards

And other things that go bump in the night

‘Cause to me every day is Halloween

I have given up hiding and started to fightWell anytime, any place, anywhere that I go

All the people seem to stop and stare

They say, “Why are you dressed like it’s Halloween?”

“You look so absurd, you look so obscene!”Oh, why can’t I live a life for me?

Why should I take the abuse that’s served?

Why can’t they see they’re just like me?

It’s the same, it’s the same in the whole wide world

The horrorcore hip-hop band clipping. is another that comes to mind. They’re not making Halloween music specifically, but one of their most popular songs “Nothing is safe” is built on a John Carpenter-esque beat, and many of their others are self-consciously about horror-related topics. They even have a song called “‘96 Neve Campbell.” Amazing.

Today, Florence & the Machine have a new album out called Everybody Scream. Clearly the release was planned for Halloween, but the subtext of the album is much darker than a holiday about getting candy. The album cover is gothic, and witchcraft provides lots of the thematic content. According to an interview she did on Apple Music, the concept for the album was inspired by an ectopic miscarriage Florence had on stage, the surgery that saved her life, and all the physical and emotional agony that went with it.

This is Halloween music, but it’s music for introspection. It’s music for screaming while spinning alone in the forest.

Basically, like the holiday itself, Halloween music isn’t easily packaged for a single use case, which is why it hasn’t been I suppose. Yes, you can look at the holiday and see the commercialism in it, but that’s always existed alongside a series of tensions. It’s fun for kids but also often the first time kids get to go out alone at night, a step toward adulthood. There’s fear and autonomy but also safety in numbers. There’s mischief and deviance but also community and neighborliness. There’s cheap, packaged costumes but tons of DIY creativity as well. There are drunken parties but also whispered gatherings and games in graveyards.

In some ways, Halloween is a great time for music simply because it’s a time for hanging out with people and listening to music.

That’s why to me, Prince is the all-time best Halloween artist. He’s always in costume. He’s unabashedly weird and mischievous. His clothing often has some gothic flare to it. He’s at home in the darkness. His music makes you want to dance, and I often listen to it at Halloween. What’s not Halloween about that?

So maybe that’s the big takeaway for musicians from all this. Maybe Halloween for musicians is less about trying to make spooky-sounding songs, which often can be kind of cliché and ridiculous (except on film), and more about letting loose the weird, liminal side of yourself, the side that wants to converse with the spirits and embrace mystery and ambiguity. Maybe it’s finding a bit of inspiration in the non-linear development of Halloween, and all the traditions associated with it — or just taking a creative impulse from death, darkness, and deviance.

What’s clear is that Halloween’s musical tradition is much more fragmented and idiosyncratic than Christmas, but maybe I prefer that anyway.

Happy Halloween,

Ian

PS. Thank you very much to Ewa Łączkowska, Hildur, Timo, Anja, Stan, SYL, and Aayati for the conversation that sparked this essay and some of the song suggestions.

Ian Temple is the Founder and CEO of Soundfly. Follow his Substack, Soundfly Weekly, or join the growing community of musicians and educators on Soundfly for free today.