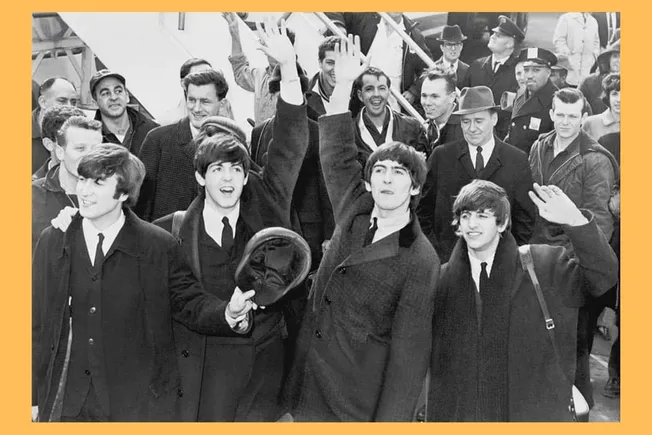

More than fifty years after The Beatles broke out into still unparalleled success, we look at five key songwriting techniques imparted onto us by the fab four.

___________________________________

Guest post by Dre DiMura of Soundfly’s Flypaper

The Beatles showed the world that you could write and perform your own songs. Fifty-six years after “Love Me Do” was released, there is still so much to learn from The Beatles and their innate sense of songcraft, which is both timeless and arguably unrivaled, even to this day.

So here is our list of five things The Beatles taught us about songwriting, in reverse order of randomness.

5. Write the BGVs.

Background vocals can often feel like an afterthought; I’d normally associate background vocals with the arranging stage of songwriting, well into the production process. This is not the case with the Fab Four. In The Beatles’ case, the background vocals were an integral storytelling tool and likely part of the writing process itself.

Take “She’s Leaving Home” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

She (We never thought of ourselves)

Is leaving (Never a thought for ourselves)

Home (We struggled hard all our lives to get by)

She’s leaving home, after living alone for so many years.

The background vocals here provide even more information than the melodic top line that denotes this section as the chorus. It’s also a clever way to incorporate a secondary Point of View (POV) into a song (SHE is leaving home / WE never thought of ourselves), which is normally considered a major songwriting faux pas.

Here’s another example from the same album, “Getting Better.” Both the verse and chorus use this technique to pontificate on the lyrics carried by the lead vocal.

I used to get mad at my school (No, I can’t complain)

The teachers who taught me weren’t cool (No, I can’t complain)

You’re holding me down

Turning me round

Filling me up with your rules.

I’ve got to admit it’s getting better (Better)

A little better all the time (It can’t get no worse)

I have to admit it’s getting better (Better)

It’s getting better

Since you’ve been mine.

Also, a nod here to bending the rules of grammar in the name of art! “It can’t get NO worse.”

One final example is in “Help!.” Although the background vocals in “Help!” don’t provide additional text, they are used to both anticipate and recapitulate what John is singing.

(When) When I was younger (when I was young), so much younger than today

(I never need) I never needed anybody’s help in any way

(Now) But now these days are gone (these days are gone), I’m not so self assured

(And now I find) Now I find I’ve changed my mind and opened up the doors.

Given the technological limits of the time, it’s hard to imagine The Beatles writing these parts in post. Many early Beatles songs had the entire band singing into a single microphone, often live, together, with the harmonies and melody on a single track.

4. The First Verse Was So Good We’re Going to Use it Again.

In a song with three verses, The Beatles often repeate the first verse as the last verse. This can be heard again in “Help!” and “I’ve Just Seen a Face.” You could chalk it up to laziness, but when used with intention, this is actually a powerful tool that can really drive home the message of a song. Especially if the verse is providing important information that can be even more powerful when reiterated after we’ve absorbed the content in the choruses.

I was on tour with Three Days Grace this summer. Their 2003 smash “I Hate Everything About You” uses the same verse twice, and it’s a bop, not to mention very singalongable. Many other artists have used this technique, such as: John Denver, Heart, INXS, Fleetwood Mac, and Celine Dion, to name a few.

3. The “60 Second” Rule.

Look out Nicholas Cage, The Beatles were gone in 60 seconds too. They had an amazing ability to pack a serious amount of fire into the first 60 seconds of a song. Many early Beatles songs introduce all of the core musical elements in the first minute, and by that I mean the verse, chorus, and yes, even the bridge.

Talk about efficiency.

In “A Hard Day’s Night,” The Beatles were able to squeeze two verses, two choruses, and a bridge into the first minute. This was a feat of olympic proportions. Different songs call for different arrangements, but it’s important to be aware of the listeners’ journey during that first impressionable minute. The Beatles were adept.

Mega producer Max Martin’s “Melodic Math” says for a song to be a hit, the chorus has to enter before 0:50 in a song; in other words, just under a minute. The Beatles made this look like an epoch — the refrain in “A Hard Days Night” drops at just 0:17.

2. Don’t Bore Us, Start with the Chorus.

The Beatles would have been an incredible streaming band (they actually still are, with over 20.6 million Spotify listeners). Their songs were built for the platforms that we are using today. Not only was the average length of a Beatles song 2:45, many of those songs began with the chorus, a common device that is increasingly popular in the streaming era.

Some examples of that would be: “Eleanor Rigby,” “It Won’t Be Long,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Lovely Rita,” “Cry Baby Cry,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and “She Loves You.” Get my drift?

Hear this in full effect in 2019 with songs like “Nothing Breaks Like the Heart” by Mark Ronson and Miley Cyrus, and “Tempo” by Lizzo (feat. Missy Elliot).

1. Don’t Forget the Bridge.

Do you remember what a bridge is? It’s 2019. The poor bridge has become a whole lot of nothing. The status quo is to copy-paste a verse or chorus, mute a couple of tracks, and add some sound design ear candy before a reverse cymbal swell takes us back into the chorus. Blah blah blah.

The Beatles wrote bridges that were so good they played them not once, but twice (“I Saw Her Standing There,” “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” “Eight Days A Week”). They were so good they could have been a smash chorus for a lesser band. The Beatles’ bridges were solid departures from the rest of the song, and helped to offset the inevitable monotony of the pop format.

Not only were the bridges distinct and unique, the band was clever in their arrangements to create added textures. Take a listen to “Ticket to Ride.”

The entire song is driven by the tambourine. Tell me I’m crazy. The verses and choruses feature a tambourine slap on beats 2 and 4, but during the bridge, it shifts to a 16th note rhythm. The transition to the bridge is even anticipated by the 16th note pattern beginning on beat 2 of the previous bar. Again, the bridge is featured twice.

Sometimes the bridge was so strong, The Beatles seemingly skipped an entire formal chorus altogether. This comes from primordial pop songwriting, when pop was largely comprised of or influenced by show tunes and big band jazz. Using a “deceptive AABA” structure, as was traditional in pre-Beatles pop music:

- The “A” section contained a verse and a refrain (chorus) over the last several bars,

- The “B” section was considered the bridge.

These days, when we talk about song structure, we normally have a clear distinction between the verse and chorus, as choruses are usually more drawn out. And would use the labels A, B, and C (for the bridge).

The point is, the bridge was really important and considered an integral part of the arrangement, because the verse and chorus were viewed as a compound phrase, thus making the bridge or traditional “B” section the only and most crucial element in keeping the listener engaged and entertained. We could continue to debate the nomenclature regarding labels and song structure, but we’ll cross that bridge when we get there…

Dre DiMura is a professional guitarist, songwriter, and author. While his friends were studying for the SATs, Dre was already touring the world with Gloria Gaynor, Dee Snider, Palaye Royale and Evol Walks. He’s a musician and he’s played one on TV too. You may see him at your local enormo-dome on tour with Diamanté.