Controlled Compositions Clauses, Frozen Mechanicals Explained

BMG recently made headlines with the announcement that they would be rolling back at least some aspects of the “controlled composition” in their record deals, which would be good news for artists, particularly if other organizations follow suit.

Guest post from Music Technology Policy

BMG announced they will be rolling back at least some aspects of what’s called “controlled compositions” clauses in (presumably) their record deals. This is good, and is another example of how BMG is setting the gold standard for courageously defending their writers.

Don’t forget, BMG sued Cox Communications for failing to maintain a repeat infringer policy that voided Cox’s safe harbor under DMCA. Nobody else joined in until after BMG won big. Now everyone wants to get into the act. BMG’s early solo move to bring justice took real guts and confidence and we all owe them a huge debt of gratitude. So this is not about them.

Let’s understand what “controlled compositions” clauses actually mean and don’t mean. The basic concept is that an artist signing to a label grants a mechanical license to the label for the songs they record that the label exploits.

So stop right there–this only covers records exploited by the label. It does not cover any streaming service, like Spotify or Apple, both of which have to obtain mechanical licenses under an NOI or soon under the blanket in the Music Modernization Act giveaway. And trust me, the blanket will be extraordinarily screwed up, but that’s a topic for another day.

Mechanical licenses and mechanical royalty payments by record companies are actually much less prone to error than those made by streaming services. Mechanical royalty payments are much more likely to get paid timely for a very simple reason–the label needs the artist/songwriter to cooperate. Screwing them on their mechanicals is not likely to win any friends. The same cannot be said of Spotify which proves every day how little they care about artists, much less songwriters. While the label may take an edge, the label’s royalty department knows that the quickest desktop audit is to compare the units on the record royalty statement to the units on the mechanical royalty statement–if they don’t match….

Plus, the metadata is much more likely to be correct at the labels–remember, the streaming services base almost all their song data off of the metadata they receive from the labels for sound recordings. Is it perfect? Probably not, but it could be. At A&M, I forced each producer delivering masters to deliver us all the song metadata and splits so that our mechanical royalty department had a place to start from. That dropped our “pending and unmatched” pool down so low that on audit the Harry Fox Agency was convinced we were hiding money. (The pending and unmatched is also called the “black box” or the McLaren & Tuition Slush Fund for SVPs and Above. Yet somehow we struggled through.) However, in the contemporary pop single with 30 writers, this won’t help you because the records get released before the splits are tied down.

Even so, the services also routinely change the name of the songs to suit whatever they think the user experience might be, among other reasons. For example, they might change “For What It’s Worth” to “What’s That Sound”. That means you can have the metadata perfect at the label, but by the time it gets to the service’s mechanical royalty statement it very likely will be screwed up. Why the trade associations and songwriter groups allow them to get away with this is anyone’s guess, but they do.

However, labels have to actually write a check for the mechanical royalties they pay out, often to the same artists who are unrecouped on the recording side of their deals. Therefore, this controlled comp thing becomes a touchy subject as the artist/songwriter is going to turn around and make a publishing deal that is not recoupable from their record royalties, but the publishing deal earns out against the mechanical royalty stream paid by the label.

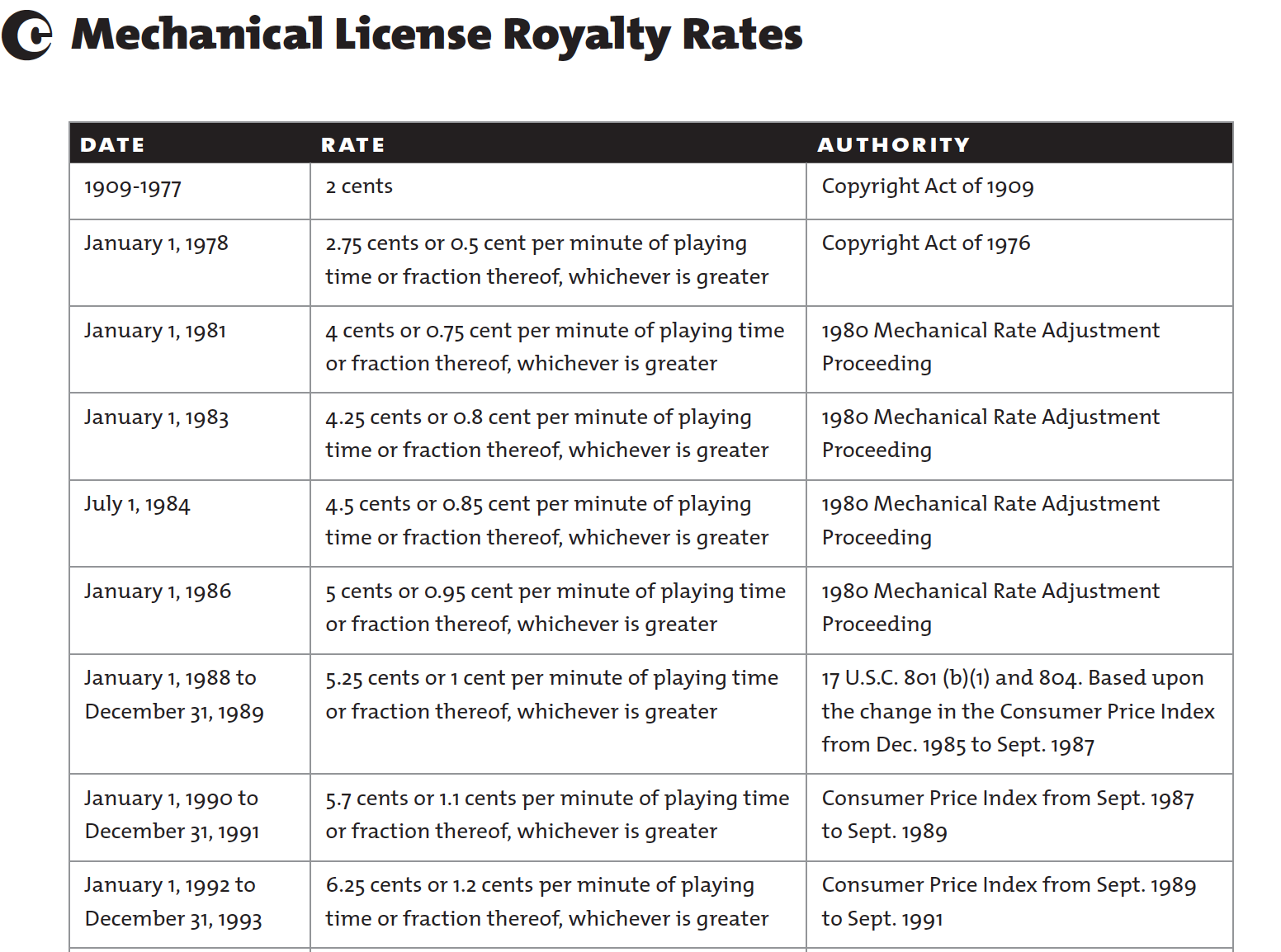

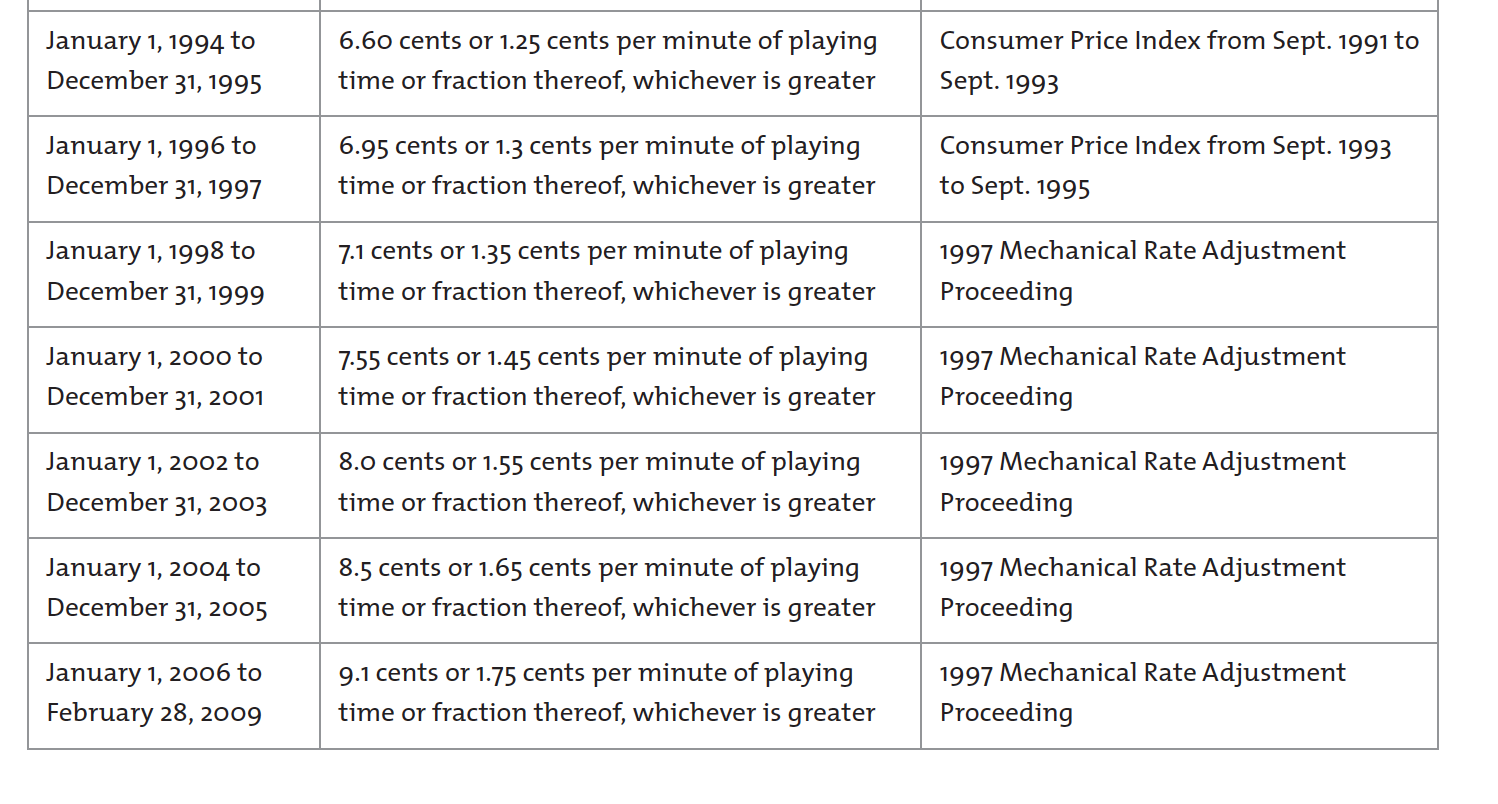

And this is where a page of history is worth a volume of logic. When the 1976 revision of the Copyright Act came into effect, the mechanical royalty rate began to increase on the effective date of 1/1/78. It had been frozen at 2¢ since 1909. That’s right–songwriters had been getting hosed for 68 years.

After 1/1/78, the mechanical rate began to increase very gradually, but that increase began to challenge the label P&L projections. It looked like this:

Note that the increases stopped in 2006–that’s not a typo. We’ll come back to that issue.

Also bear in mind that the average artist royalty in pennies for signed artists is somewhere in the vicinity of $1.50 to $2 per compact disc and that the average running time of a CD is about 70 minutes comfortably using red book audio and you can push it to about 75 minutes. If songs have a running time of about five minutes on average that’s a maximum of about 14 songs. At 9.1¢ per song, that’s $1.27ish per disc. (Let’s leave aside long song formulas.) That’s getting very close to the average new artist per-CD royalty rate. Under the pre-1978 rate, 14 songs would have been a 28¢ mechanical.

It became very apparent that mechanical royalties were about to start catching up very soon. The rate doubled in 1981 and quadrupled in 2002. So just like labels negotiated a cap on CD rates in the 80s (“same pennies as black vinyl”), around the same time they also started negotiating what was called the controlled compositions terms for the songs on the CD.

Of course, denying something to any good artist lawyer is just postponing capitulation. It was only a matter of time before controlled comp clauses started getting weaker and weaker. Realize that it is very often the case that a label has an affiliated publisher. If you sign with the affiliated publisher, you essentially should ask for no or very limited controlled comp terms. You can see that if they give you a better deal when you sign with their publisher and a worse deal if you don’t, they are using the controlled comp terms to drive you to their publishers.

The basic controlled comp terms are:

75% of the statutory rate in the US and Canada the dreaded 3/4 rate. (Realize that there really are no controlled comp terms outside the US and Canada and even in Canada the CMRRA has long negotiated away certain parts of the typical controlled comp clause as far as sales in Canada are concerned). Remember, this is for physical and permanent downloads–but permanent downloads usually get paid at full rate for the asking. What you also have to watch out for is the “3/4 of 3/4” clause which can include a variety of configurations. Too little attention is paid to the 3/4 of 3/4. When record clubs were the rage they got this 3/4 of 3/4 rate. So requiring full statutory for record clubs was a good way to stay out of the clubs as they often refused to pay the full statutory mechanical rate. You can usually get the 75% increased up to full based on sales levels, often with an interim tier at 87-1/2%. You can also ask for the next LP to start at the highest rate the last LP achieved, so if you were able to punch through to full rate on LP1, LP2 would start at full rate, but if you failed to punch through your sales levels on LP2, then LP3 would start over at 75%.

Fixation Date: More of a US issue, the controlled comp rate takes the statutory rate in effect at the time of recording, but you can negotiate time of release (which will be later). See the chart above to understand this better–up until the rate was frozen in 2006 it mattered. Now it doesn’t but they won’t change the language in case it gets increased later. The fully negotiated version of this is a floating rate so it’s the rate in effect when the record is sold. You should also ask for fixation date of release for greatest hits, best ofs, or compilations.

Maximum Aggregate Mechanical Royalty: This is the “10 song cap.” The label wants to protect their downside so they say they will only pay mechanicals on 10 songs. You can usually get 11 song cap for the asking and sometimes you can get higher than that if the label asks for an 11th or 12th song or adds a bonus track. You can also get “protection” for “outside songs” or fractions thereof at full rate, particularly if the label asks the artist to write with an outside writer or a producer who writes (or writes themselves in which is becoming a common battle). This also can include samples. “Protection” covers these outside songs because if you start deducting full rate to outside writers from the cap rate, the mechanical pool (sometimes called the “controlled pool”) that’s left can decrease very quickly.

So at a 9.1¢ full rate, the aggregate mechanical would be 10 x 9.1¢ or $0.91 x .75 or $0.6825. This is the “cap rate”. If you have the equivalent of 1 full rate outside song with no protection plus 10 songs subject to the cap, that leaves $0.5915 as the “mechanical pool” or “controlled pool” (meaning the aggregate mechanical available to be divided among the artist/songwriters). Each song then gets 5.915¢ instead of 9.1¢ or even 6.825¢ with protection. See why you want protection? (See also Carefully Co-Writing without Creative Commons.)

Also realize that if there are a lot of samples when publishers of the samples take big splits of the new song, it’s possible to go negative on the mechanical cap. In that case, the amount in excess of the mechanical cap becomes a deduction from the artist record royalty. That’s right, it is possible to earn less than zero on a record with heavy samples or even have the overage treated as an additional advance that reduces future contractual advances to the artist.

Realize that if you have a successful artist with some co-writes with outside writers, each album release is its own mechanical royalty negotiation so whatever the contract says it’s a starting place. In renegotiations, the cap is always raised, but usually not beyond 12. If you can get more than 12x cap, you know who you are.

And of course the controlled mechanical is only payable on one version of the song (so if you put out a remix album with multiple versions pay attention to this clause).

Payment on Royalty Bearing Sales: There is a long history of non-royalty bearing “sales” which are sometimes called “free goods” or “breakage”. The typical controlled comp clause only pays mechanicals on royalty bearing sales, so naturally that gets negotiated. You should be able to get paid on 50% of standard sales plan LP (or all) free goods for the asking. Remember–free goods are another form of discount. A label can sell a retailer 10 CDs for $100 with a 10% discount or a $90 net payment. Or the label can sell the retailer 10 CDs for $100 but give an additional 1 “clean” for free which the retailer can sell (and possibly return). And when the retailer sells the 11 units, they will likely all get picked up on SoundScan and counted as a sale, even if they weren’t all “sold” by the label to the retailer who reports to SoundScan. This is why labels get calls from publishers saying I see my #1 single scanned X units but I got paid on 80% of X so where’s my mechanical royalty for the other 20% of units? This is because of a 20% discount in free units that got sold and scanned. At which point the label may say, great, I’ll invoice you for 20% of the indie bills, tour support and marketing costs and you can get your mechanical on the frees, deal?

Let’s also discuss the most recent frozen mechanical royalty. For all the arm waiving, chest beating and credit taking for the Music Modernization Act giveaway, one of the many things that nobody fixed is the frozen mechanical for physical. Remember–nobody fixed the frozen mechanical for physical from 1909 to 1977, either.

The mechanical has been frozen since 2006 and does not look like it’s going to change any time soon. In fact, I’ve had people say to me that they were so clever for getting the labels to “agree” to freeze the mechanical for physical and permanent downloads. (This is more like a gift than a give.) Why? So the labels would not oppose going after the services for a higher streaming mechanical which the labels don’t have to pay anyway and that starts several decimal places to the right, while physical still accounts for a huge chunk of sales. And they say this like they’ve said something clever. When you hear this, you think, oh, this is a strategy, I see. Silly me, I thought it was just stupidity.

Remember, by freezing the mechanical rate for 14 years, the 9.1¢ mechanical is essentially worth about 30% less just due to inflation. So even if you get rid of the 3/4 rate but you don’t increase the mechanical for inflation, you haven’t gained much. And remember, an increase for inflation just maintains buying power, it’s not really an increase.

So we appreciate BMG getting rid of controlled comp clauses or at least the 3/4 rate if that’s what they are doing. Any activity in that direction is welcome.