Chris Castle explains why he beleives you should fight big tech companies and demand your contracts and royalty earnings.

Op-Ed by CHRIS CASTLE of Music Tech Policy

As I posted recently (“Google’s Shameful Bullying Tactics on Display Again in CRB“), Google has once again turned its lawyers loose to run roughshod over songwriters in their latest theater of lawfare, this time the Copyright Royalty Board in the rate setting for streaming mechanicals. They are using their bottomless litigation budget to treat the government’s rate-setting agency as though it was a Federal court hearing a copyright case where Google was hell-bent on stealing someone else’s work product (like the widely criticized decision in Google v. Oracle). It’s all the same to Google and their grotesquely maniacal legal crew. File this under News from the Goolag.

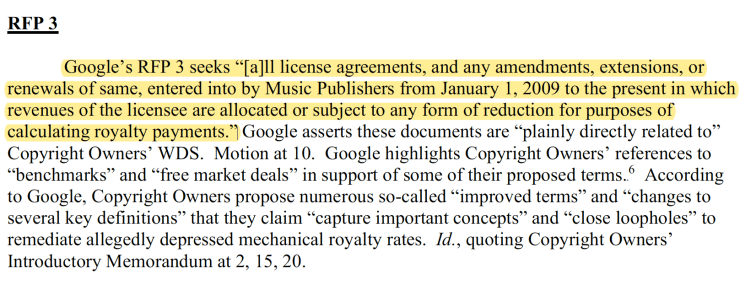

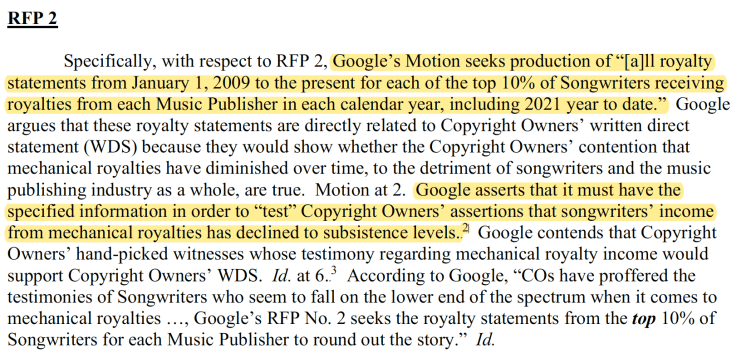

The latest attack by the Google bullies is to force participating publishers to hand over copies of royalty statements and licenses so Google can prove what we all know–songwriters have gotten hosed by digital services like YouTube since Google decided to litigate their way to a “DMCA license”. That’s right–after the government took away songwriters’ rights to set their own prices with the compulsory license, Google is now using the government’s own rate court to prove that songwriters are paid too much.

Read that again: Google is now using the government’s own rate court to prove that songwriters are paid too much.

That’s right–the sick puppies are running the kennel. And there is an endless supply of sick puppies on display at the Copyright Royalty Board.

So this is the world we live in now. The government takes–there’s that word again–away your rights and freedom to contract and consequently the government forces you to submit to the decisions of their “rate court” that sets perpetual wage and price controls. Why? Because at the turn of the century something happened that looked like a market failure under some standard in effect at the time. And oh, right–“turn of the century” is the turn of the 20th Century, not the 21st. So we currently have to live by rules set in 1909 when the proverbial playing field was a lot more level than it has been in a very long time and nobody can remember what the original sin was that required generational punishment. We are way beyond “sins of the father” now.

Today we have to go into the same process in the Copyright Royalty Board (which had many predecessors and different titles, but all did essentially the same thing on a high level–tell you what you could charge for a song). The difference is the sick puppies. The difference is that before streaming, the users of the license were mostly record companies who had a vested interest in songwriters being sustained if not successful and surviving to create new works. The record companies were (and are) tough negotiators, make no mistake. But they weren’t like the services and their obsession with commoditizing everything their networks touch, which is everything.

Radiohead’s Thom Yorke has a striking interview in the Guardian in which he sums up the band’s realizations about what David Lowery calls the “New Boss” reality:

“[Big Tech] have to keep commodifying things to keep the share price up, but in doing so they have made all content, including music and newspapers, worthless, in order to make their billions. And this is what we want? I still think it will be undermined in some way. It doesn’t make sense to me. Anyway, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. The commodification of human relationships through social networks. Amazing!”

He is, of course, exactly correct. What does this “commodification” or the Americanized, “commoditization” mean exactly?

In a prescient 2008 book review of Nicholas Carr’s The Google Enigma (entitled “Google the Destroyer“), antitrust scholar Jim DeLong gives an elegant explanation:

Carr’s Google Enigma made a familiar business strategy point: companies that provide one component of a system love to commoditize the other components, the complements to their own products, because that leaves more of the value of the total stack available for the commoditizer….Carr noted that Google is unusual because of the large number of products and services that can be complements to the search function, including basic production of content and its distribution, along with anything else that can be used to gather eyeballs for advertising. Google’s incentives to reduce the costs of complements so as to harvest more eyeballs to view advertising are immense….This point is indeed true, and so is an additional point. In most circumstances, the commoditizer’s goal is restrained by knowledge that enough money must be left in the system to support the creation of the complements [in our case, the writing of songs]….

Google is in a different position. Its major complements already exist [called “catalog” or “evergreens”], and it need not worry in the short term about continuing the flow. For content, we have decades of music and movies that can be digitized and then distributed, with advertising attached. A wealth of other works await digitizing – books, maps, visual arts, and so on. If these run out, Google and other Internet companies have hit on the concept of user-generated content [under the “DMCA license”] and social networks, in which the users are sold to each other, with yet more advertising attached.

So, on the whole, Google can continue to do well even if leaves providers of is complements gasping like fish on a beach.

Are you surprised that Google over-lawyers the Copyright Royalty Board using lawfare to crush songwriters in an economic pile-driver and leave them “gasping like fish on a beach”? You shouldn’t be, because this is what monopoly looks like. But what can we do to stop it?

Aside from a Congressional campaign to overhaul the entire system to stop CRB abuse, there may be direct action that songwriters can take. First, you can write to the Copyright Royalty Judges and tell them you don’t want Google rifling through your statements under the protection of a court order. But there may also be some contractual protection you can seek from publishers.

First, understand the issue in its simplest form: The government takes–ahem–away your rights, tasks the CRB with divining what a free market rate would be when there has never been a free market rate for mechanical royalties (since 1909 but let’s call that “never” for our purposes). This unenviable task requires the judges to guess at what that rate would be. A common way for the Judges to guess is for the lobbyists representing the publishers to give them “benchmarks” or examples of other deals that were negotiated outside of the statutory license. This usually comes with an argument that the statutory rate needs to increase to free market rates given the benchmarks. (Which inevitably gets into an argument about whether the publishers’ lobbyists are cherrypicking the bench marks and on and on and on.). This allows everyone to pretend they are not guessing at a rate, which of course they are.

What Google is doing rifling through your statements is trying to disprove the benchmarks to harm you. The assumption is that all the songwriters at all the publishers were included in the benchmark references which is probably true.

Let us accept as a given that the entire process is stupid and is an extraordinarily half-hearted (or something) way to get to go. Since nobody ever asked if you wanted to be included, how can you opt out and maintain some shred of privacy in the face of the largest privacy victimizer in the history of mankind represented by unchained rabid lawyers who intend to lay waste to any possible shred of your sense of self just so you understand who’s really the boss here? Or at least who’s way richer than you thanks to the government’s failure to protect you from the DMCA notice and income transfer. (MTP readers will recognize what I call the ennui of learned helplessness.)

The first thing you can do is try to prevent your publisher from including your deals and statements in any benchmarking exercise at the CRB. Because all these particular and offending CRB subpoenas are based off of benchmarking, if you do not allow your publisher to include your deal in their benchmark, there’s at least an argument at that point that your statements and licenses should not be produced because they are irrelevant to the entire benchmark exercise. Your statements should be excluded from either side of the proof because they were not included in any side of the proof in the first place.

In any event, if for any reason your publisher is required to produce your licenses and statements, they should agree to notify you before they do so and give you an opportunity to try to stop that production, which usually takes the form of a motion to stop (or “quash”) the subpoena at least as to you.

Publishers are clearly not asking their writers (past or present) what they think or want by the look of it. But there’s got to be something songwriters can do to #StopCRBAbuse by Google and its henchmen.