As a new wave of Gen Z fans flock to Steely Dan after songs like “Dirty Work” (featured on HBO’s Euphoria) go viral, the ’70s dad rock band is becoming hip with the kids.

by Henry Luzzatto from the Chartmetric Blog

Steely Dan was always terminally uncool.

This isn’t really an opinion on their music so much as their existential condition. Before they were Steely Dan, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker were old-school nerds writing “nutty little tunes” together at Bard College, bonding over their love of weird, wild reference points from “jazz, W.C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, science fiction, Nabokov, Kurt Vonnegut, Thomas Berger and Robert Altman films” to “traditional soul music and Chicago blues.”

While the late ‘60s saw rock music test the boundaries of subject matter, gender presentation, and tonality, Fagen and Becker instead aspired to become corporate songwriters in the Brill Building style, where they found mixed success. They composed “I Mean to Shine” for Barbra Streisand’s 1971 album Barbara Joan Streisand, but the song didn’t catch on. In fact, it currently has the fewest streams on the album, with just over 50k on Spotify.

https://open.spotify.com/track/352h5Y2jwHoG9luLBpiK1A

The pair realized their compositions were too complex for their setting and relocated to the West Coast, forming Steely Dan with a rotating cast of expert session musicians. Under Fagen and Becker’s obsessive, stimulant-fueled perfectionism, Steely Dan evolved from an oddball pop-rock band into an impeccably engineered studio project.

To someone steeped in proto-punk and indie of the same era, Steely Dan represented everything unappealing about the excess of the ‘70s studio sound — a band so into cocaine and cleverness that they engineered all the passion and energy out of their music. Their overtly literate lyricism was clever but self-conscious, a far cry from the visceral howl emerging from the heart of punk rock, while their musical inspirations — show tunes, easy listening, jazz, funk, and lounge music — were always handled with a sense of fundamental irony and distance, subverted with strange chords and quirky lines to distract from the music’s foundations in kitsch. No matter how complex the songs were, they always felt too clean to stand out. Like particularly high-end elevator music.

So why, I wondered, is Steely Dan showing up all over my TikTok For You Page, my news feed, and the pages of music blogs?

In part, you can blame John Mulaney and Nick Kroll. Their brilliant 2017 show, Oh, Hello on Broadway, is replete with Steely Dan references, including a spot-on parody of the song “FM” that even garnered praise from Donald Fagen himself. Because of the show’s 2017 release date, it is difficult to gauge its direct impact on growing the band’s streaming numbers. However, Oh, Hello clearly demonstrated the way demographics were shifting around the band’s audience. Kroll and Mulaney, two millennial comedians, shined a spotlight on a traditional bastion of dad-rock, but did so with equal amounts of reverence and mockery.

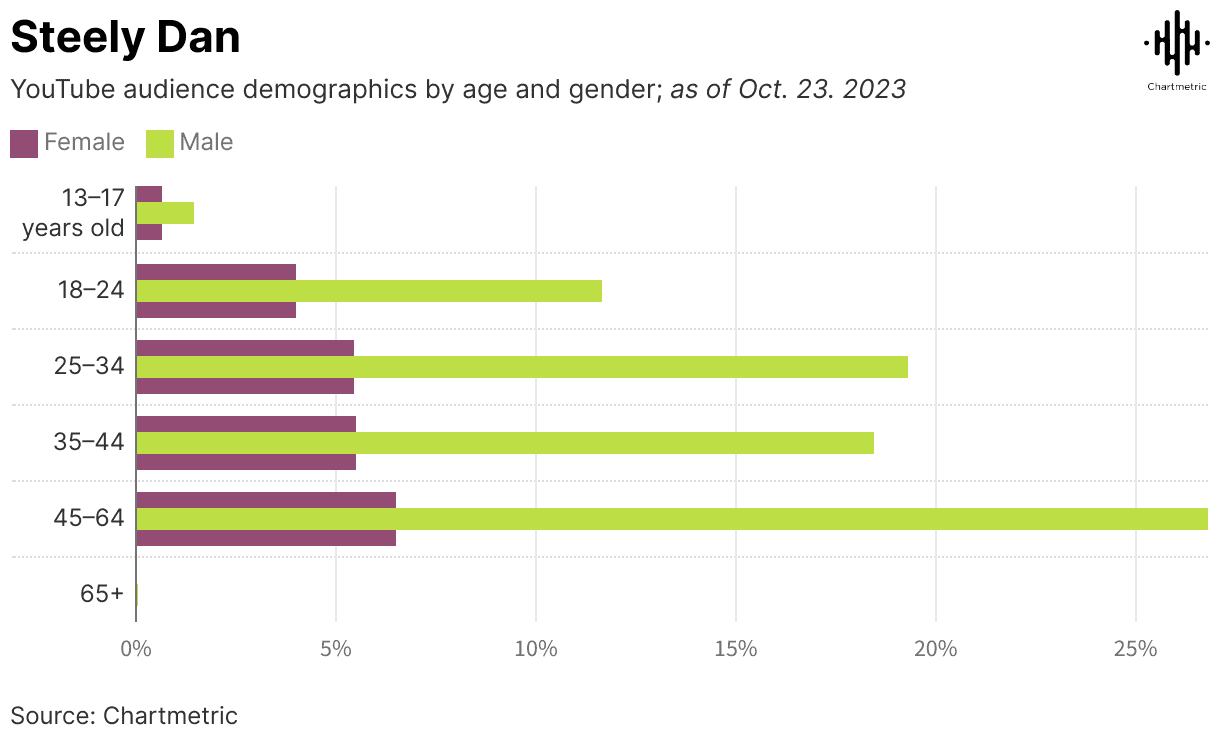

Millennial fascination with Steely Dan straddles the line between the ironic and the sincere. Derek Robinson’s 2021 article in The Ringer pointed to the band’s synthesis with absurd, modern social media meme formats, as Steely Dan-specific accounts run by jaded Brooklynites — from “good Steely Dan takes” to “people dancing to Steely Dan” — post about the band with a mix of mockery and appreciation. These accounts make a joke out of “stanning” a 50-year-old band, but they come from a clear place of care for the music. The increased attention on the group isn’t just ironic, but has translated to legitimate cultural impact. YouTube demographics show that millennial men are the second biggest viewing block for Steely Dan’s content, second only to baby boomers who were around for the band’s original run. In perhaps the most revealing shift in millennial opinion, the millennial music tastemakers at Pitchfork gave the band’s 1979 album Aja a rare 10.0 rating in their 2019 re-review.

It makes sense. In part, the re-adoption of the Dan is a refutation of the “authentic” slacker/punk aesthetic that dominated Gen X — a perspective best represented by infamous alt-rock production maven Steve Albini, who declared on Twitter “I will always be the kind of punk who shits on Steely Dan.” For millennials, it’s no longer punk to shit on Steely Dan. In a musical context where modern indie artists from Black Midi to Arctic Monkeys have increasingly embraced influences from jazz, world music, show tunes, and lounge music, suddenly Steely Dan’s synthesis of different genres becomes appealing and ahead of its time instead of feeling like a dated cocktail of cheesy reference points. As St. Vincent, one of the most essentially millennial of all millennial artists, said in response to the above Albini tweet, “For the record — I FUCKING LOVE STEELY DAN.”

But, while Steely Dan has seen their image rehabilitated among millennials, this trend did not immediately translate to attention from Gen-Z on new media platforms like TikTok. Instead, that took a little “Dirty Work.”

https://open.spotify.com/track/3IvTwPCCjfZczCN2k4qPiH

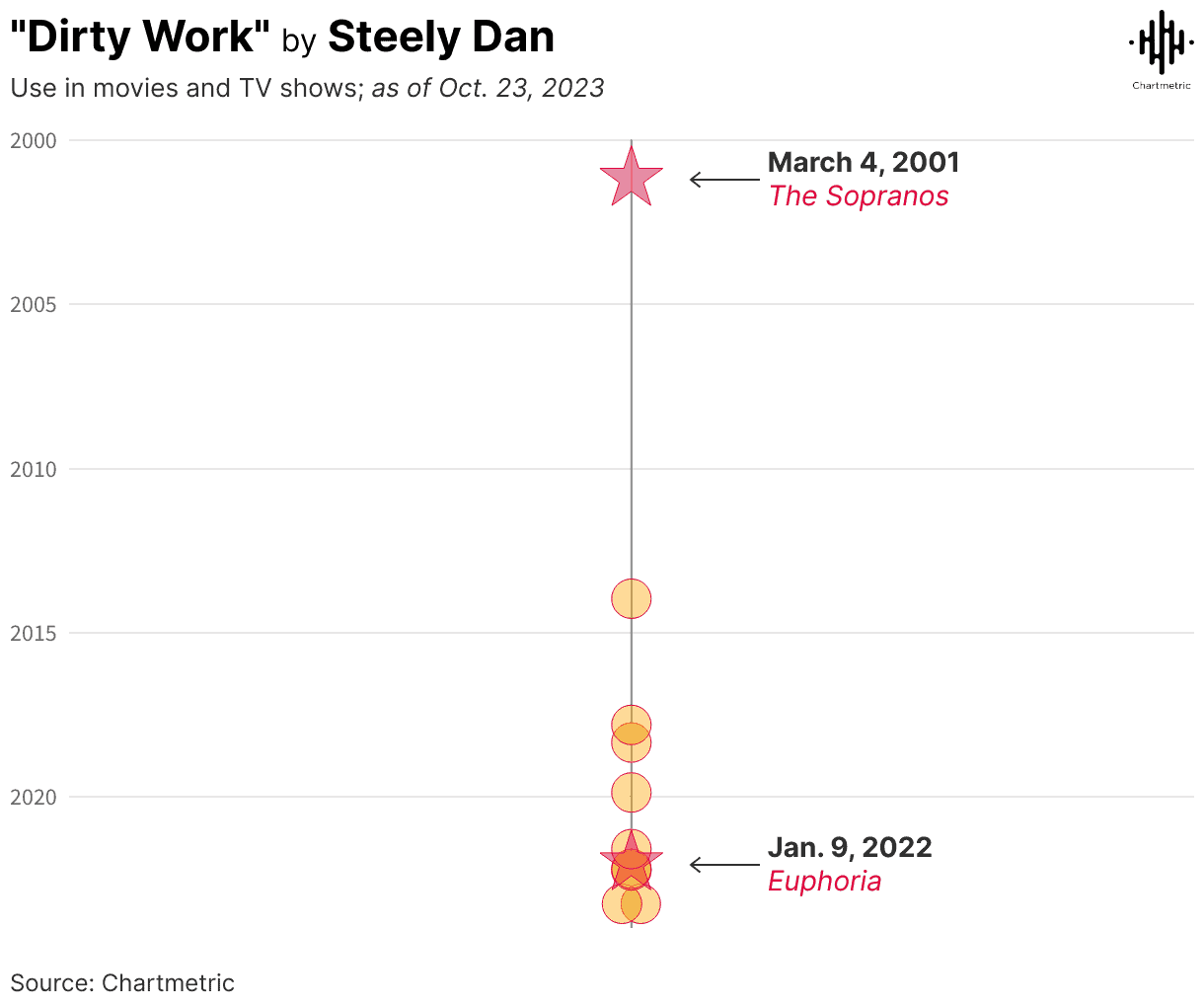

“Dirty Work,” from Steely Dan’s 1972 debut album Can’t Buy a Thrill is maybe the band’s most ubiquitous song online. Its staying power is thanks in part to some amazing guest vocals from Tony Soprano in a now-iconic scene from the HBO series, The Sopranos. The video circulates on Twitter every now and again, but while it has a definite cultural impact in the millennial meme-space, it took an appearance on a different HBO show for the band to trend on TikTok.

“Dirty Work” featured heavily in the season 2 premiere of HBO’s Euphoria, the drug-fueled high school drama that has become a cultural juggernaut for Gen-Z. It’s used as a sort of musical punchline in the episode itself. The song’s catchy, upbeat chorus line, “I’m a fool to do your dirty work (oh yeah),” kicks in immediately after an intense, harrowing strip search sequence in a trap house. The song stands out in the moment, as the cheery, anachronistic 1970s chords provide a comic juxtaposition to the show’s distinctly defined 2020s aesthetic, all while the layered vocal harmonies describe the same “dirty work” happening onscreen.

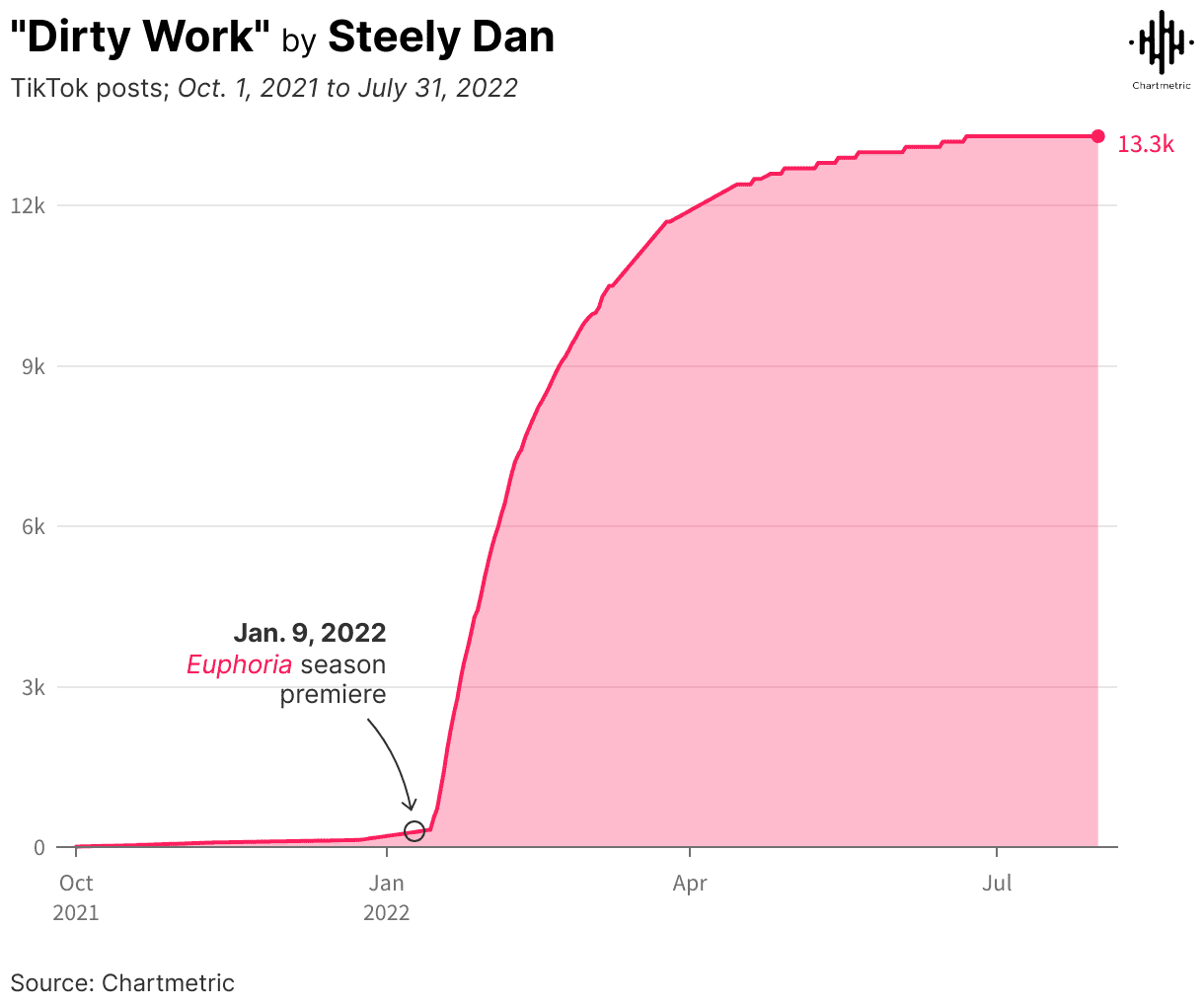

While “Dirty Work” had existed as a TikTok sound for months prior to this premiere, it exploded in usage after appearing in Euphoria. Before the episode’s premiere on January 9, 2022, the song had featured in just under 300 videos on the website, but one month after the episode’s release, it had featured in more than 7.3k videos, ultimately leveling out at around 13.3k posts.

In the nearly two years since, the song has consistently featured in viral videos that range from Euphoria references to earnest 70s fashion inspo to ironic memes about crapping your pants. That’s the thing that “Dirty Work” represents best about Steely Dan’s particular style: its sound is cheery and bright enough to be used for the background music of a “yacht rock” themed video, while there’s enough sardonic irony in its lyrics that it can function as a punchline in not one, but two, HBO series.

The boom of “Dirty Work” saw a consistent increase in the use of other Steely Dan songs on TikTok, as well. Before the Euphoria premiere, “Peg,” off Steely Dan’s 1979 opus Aja, had been used in just under 100 videos, but after the premiere, it saw an upsurge in growth. Now more than 1.8k posts have used the official sound. “Do It Again” saw similar growth in TikTok numbers as a response to Euphoria’s premiere, with relatively static TikTok engagement before “Dirty Work” began blowing up on Tiktok, where it has since been used in 4.5k posts. It seems that the use of “Dirty Work” in Euphoria didn’t just introduce on specific song to the younger TikTok audience, but instead led to increased visibility for the band as a whole.

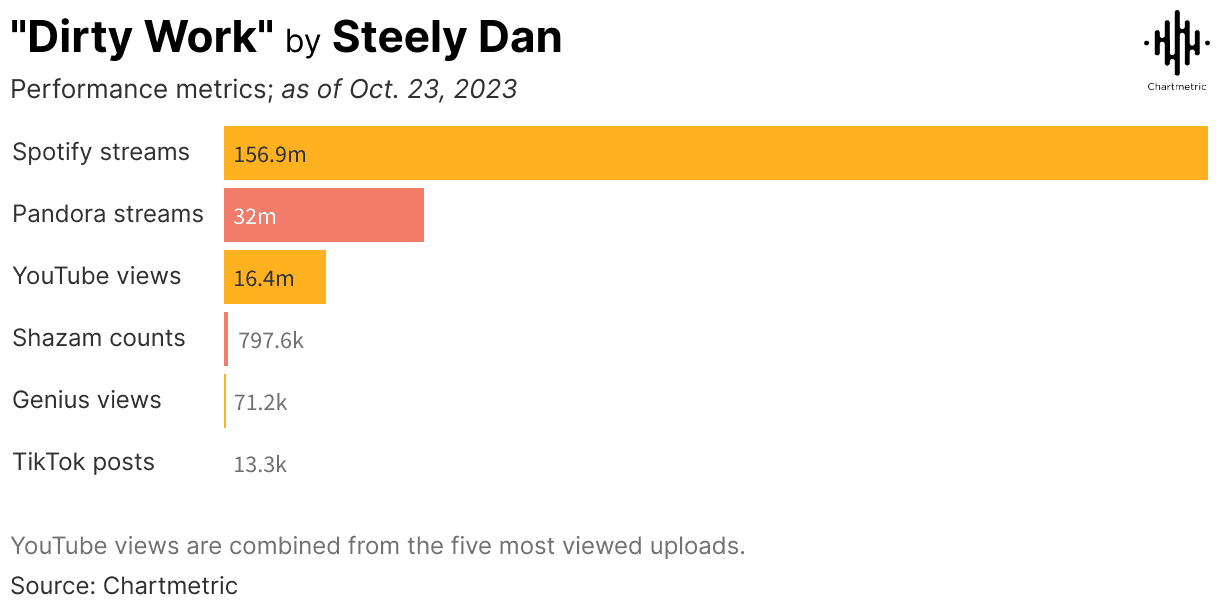

Despite not originally featuring as a single and never officially charting in its 50 years of chart history, “Dirty Work” has proven to be one of the band’s most consistently popular songs on streaming, with a Spotify popularity score of 73 out of 100 and total streams over 157 million. Comparatively, “China Grove,” the 1973 number-one single by soft-rock contemporaries The Doobie Brothers that is featured on several of the same editorial playlists, only has 138.7 million streams on Spotify. This demonstrates the increased streams that can come as a result of a song’s cross-platform and cross-meme cultural resonance.

Steely Dan isn’t the first ‘70s band to have a cultural resurgence among Gen Z. Fleetwood Macexperienced a major revival over the last few years, with the song “Dreams” re-entering the charts in 2020, largely thanks to a viral TikTok of Nathan Apodaca riding a skateboard while listening to the song. The song became a huge trend on the platform, where it has been used over 644k times. But, while Fleetwood Mac had an iconic viral video that launched their resurgence, there’s no one singular Steely Dan trend that has taken over TikTok, been turned into an Amazon Prime series, or become a point of everyday conversation.

Instead, as Chelsea Leu wrote in a New Yorker essay about her experience with the band, “The way that people get into Steely Dan is usually fuzzy, a gradual awakening rather than a bolt of pure feeling.” The band’s small but steady increase in social media interaction, from Twitter to Spotify to TikTok, shows that this gradual awakening has every chance of continuing into Gen Z and beyond.

Steely Dan’s music always felt like a bit of a contradiction. The mannered, perfectly engineered music seemed discordant with the acerbic lyrics, like it was designed to keep the audience at a distance. However, Steely Dan’s dual appreciation among millennials and Gen Z shows the way these contradictory elements can resonate across generations. Songs like “Deacon Blues,” “Peg,” or “Dirty Work” can fit just as well in an ironic meme or a Sopranos reference as they can in a “get ready with me” video featuring thrifted bell-bottoms. They’re serious enough that they can be parodied, but funny enough that Donald Fagen would perform that parody song.

Sure, they might be uncool to people like me or aging punks like Steve Albini. But, I’m sure at this point, our opinions are just as irrelevant to young, Steely Dan-inspired musicians as Steely Dan’s perspective felt to us.

Two months ago, Steely Dan announced a re-pressing of their 1979 masterpiece, Aja. And while I personally won’t be waiting in line to purchase it, there’s something exciting about knowing that that line could contain everyone, from cool to uncool, from boomers to millennials to Gen Z, from those who love Steely Dan ironically to those who just crave the sounds (and perhaps substances) of 1970s California.

Graphics by Nicki Camberg and cover image by Crasianne Tirado; data as of Oct. 24, 2023.