More than 30 years after Kathleen Hanna and company revolutionized the concept of women in rock, a new breed of loud and proud feminists from across the pond are determined to once again shake things up.

by Jon O’Brien of Chartmetric

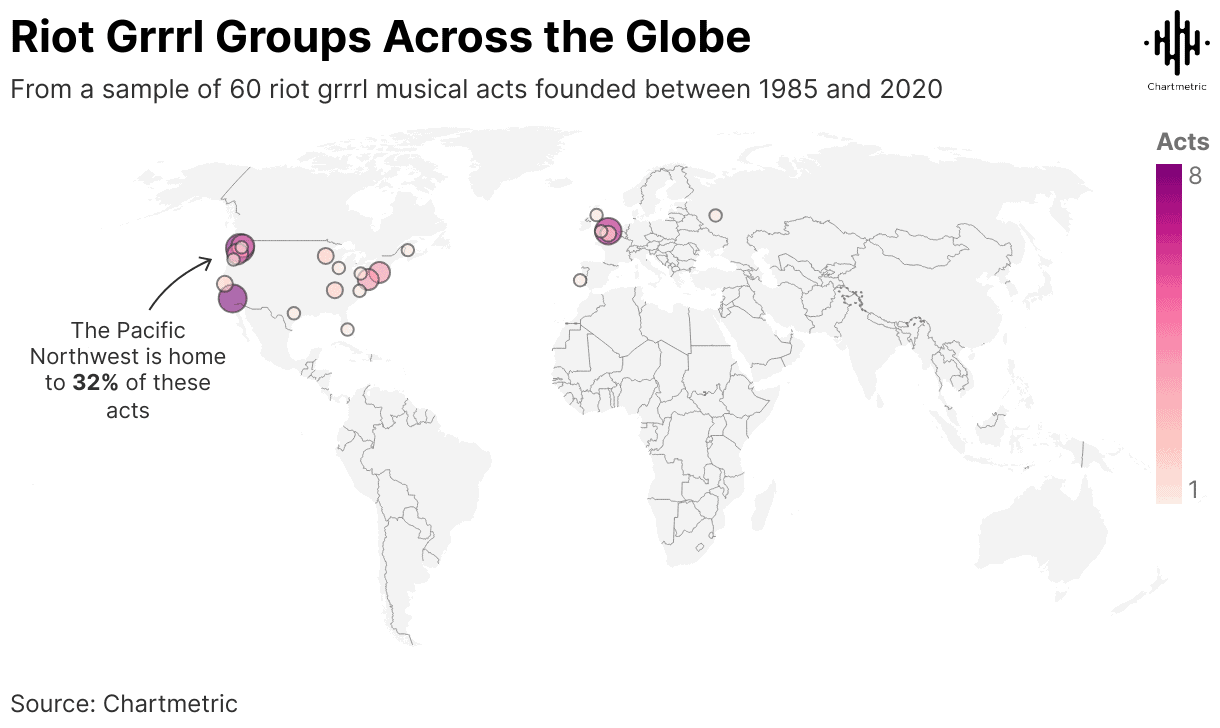

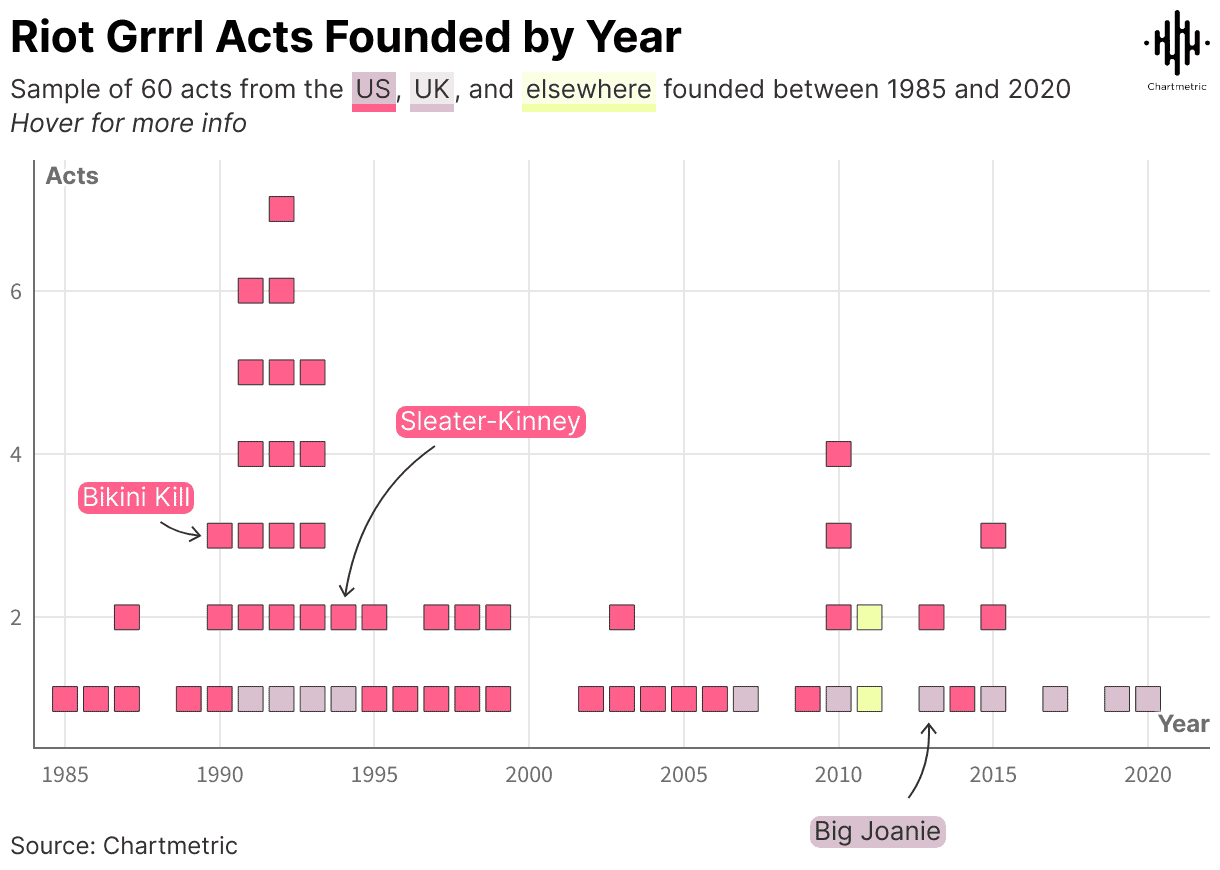

The riot grrrl subculture is as synonymous with the city of Olympia, Washington as it is ear-shattering decibel levels, provocative underground fanzines, and pure unadulterated rage against the patriarchal machine. After all, it was there where Kathleen Hanna delivered the manifesto that defined the scene’s zine subculture, where the likes of Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, and Bratmobile galvanized a generation of guitar-wielding third-wave feminists at the seminal International Pop Underground Convention, and where the deliberately misspelled term itself — designed to reclaim the patronizing way the hyper-masculine rock world referred to women — was first coined. Yet, more than 30 years on, it’s on the other side of the Atlantic where “all girls to the front” is being shouted the loudest.

However, this British-led revival isn’t as incongruous as it may initially seem. Homegrown acts such as X-Ray Spex, The Slits, and The Raincoats were all pivotal influences on the original riot grrrls, while Huggy Bear, the camera-shy “boy-girl revolutionaries” who released a split album with Bikini Kill, hailed from Brighton. Fittingly, this English seaside resort has also birthed the band most hellbent on bringing the early ‘90s movement kicking (and literally) screaming into the 2020s.

Formed during lockdown in response to the misogyny they believe is still rife within the music industry, Lambrini Girls is the brainchild of guitarist Phoebe Lunny, bassist Lilly Macieira, and a masked drummer purporting to be art world disruptor Banksy. Their unapologetically brash sound undeniably shares the same DNA as riot grrrl’s pioneers — the trio essentially told Sleater-Kinney “We’re not worthy!” in a recent joint interview with Kerrang. But while their bone-crunching riffs and pulverizing beats possess an air of familiarity, their lyrical themes are a little more transgressive.

“Help Me, I’m Gay,” for example, is a brilliantly subversive riposte to the modern media’s tendency to fetishize queer women. Meanwhile, “Terf Wars,” an amusing smackdown of gender-critical (aka trans-exclusionary radical feminist) keyboard warriors (“There’s a reason your kids aren’t returning your calls, Carol/It’s because you’re being transphobic on Facebook again”), saw them become a new nemesis of arguably the most obsessive, Irish comedy writer Graham Linehan.

Of course, the riot grrrl scene itself is no stranger to such anti-trans rhetoric. Tribe 8, The Butchies, and Hanna’s other pioneering feminist outfit Le Tigre repeatedly played at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival across the ‘90s and ‘00s. This event excluded any attendees who weren’t marked as female on their birth certificate, though Hanna has since expressed her support for trans rights. It’s this questionable past that has made the Lambrini Girls reluctant to fully embrace the riot grrrl tag, arguing to Rolling Stonethat much of the genre’s core audience still aligns with such regressive ideals.

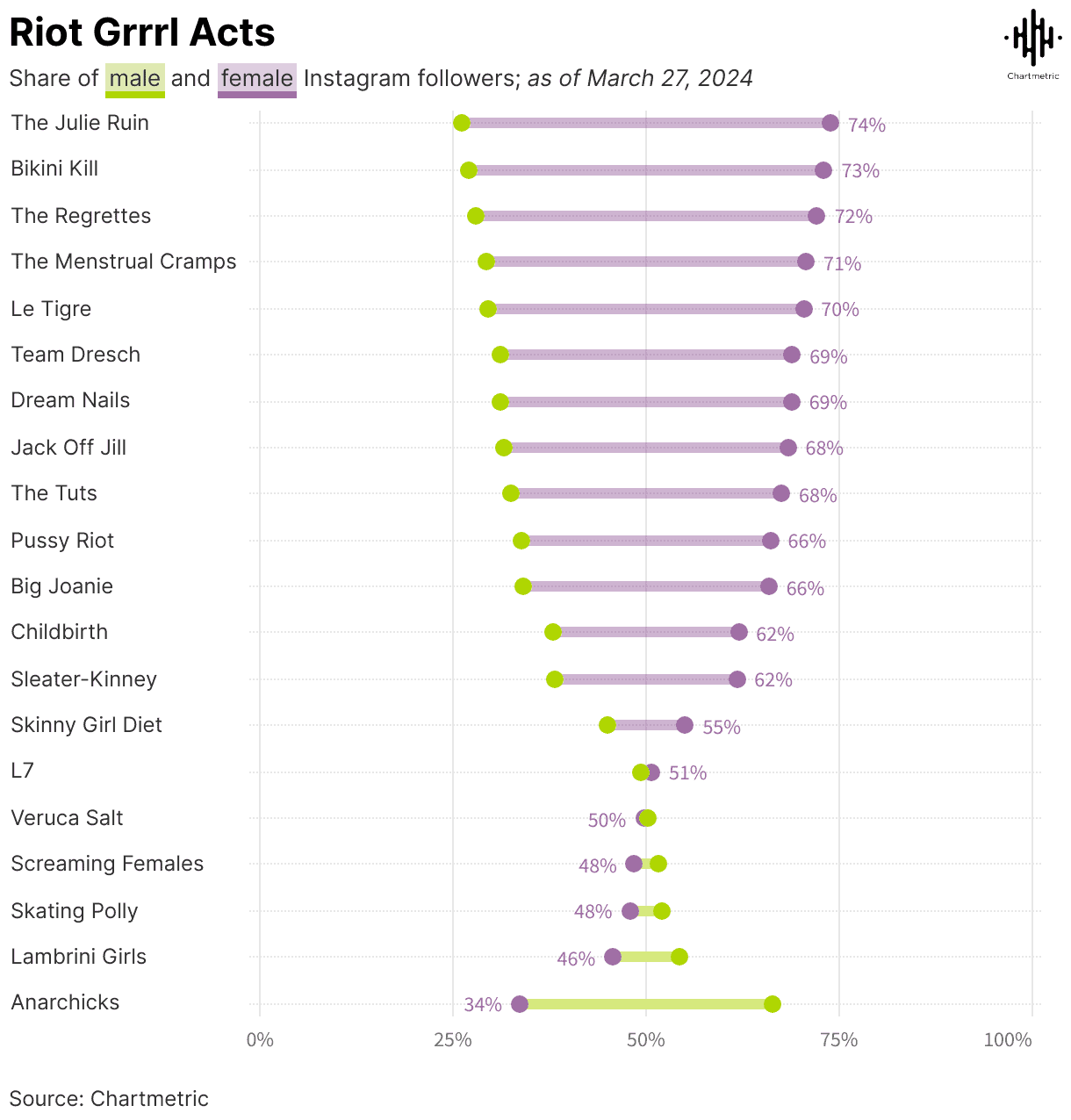

Lambrini Girls, whose Instagram followers unexpectedly skew slightly towards men, aren’t the only part of this new wave to express such concerns. Although she paid tribute to Hanna’s influence, bassist Mimi Jasson of Dream Nails – then working on their debut album – also acknowledged to The Skinny in 2018 that “the scene was not entirely inclusive.” That’s perhaps indicative of today’s breed, who seem determined to change the narrative while still recognizing how the old guard pushed things forward.

And let’s not forget just how radical the original riot grrrls were, musically, aesthetically (no one else was wearing their combat boots, fishnet stockings, and pinafore dress combo), and thematically. The early ’90s scene sprouted from a desire to validate the kind of women’s experiences largely ignored by the mainstream, and neither sexuality nor race was ever a barrier to its loud and proud brand of feminism. In fact, it was particularly committed to gay rights and fighting for them in a non-heteronormative manner, too. But as with any movement, it’s had to learn to adapt.

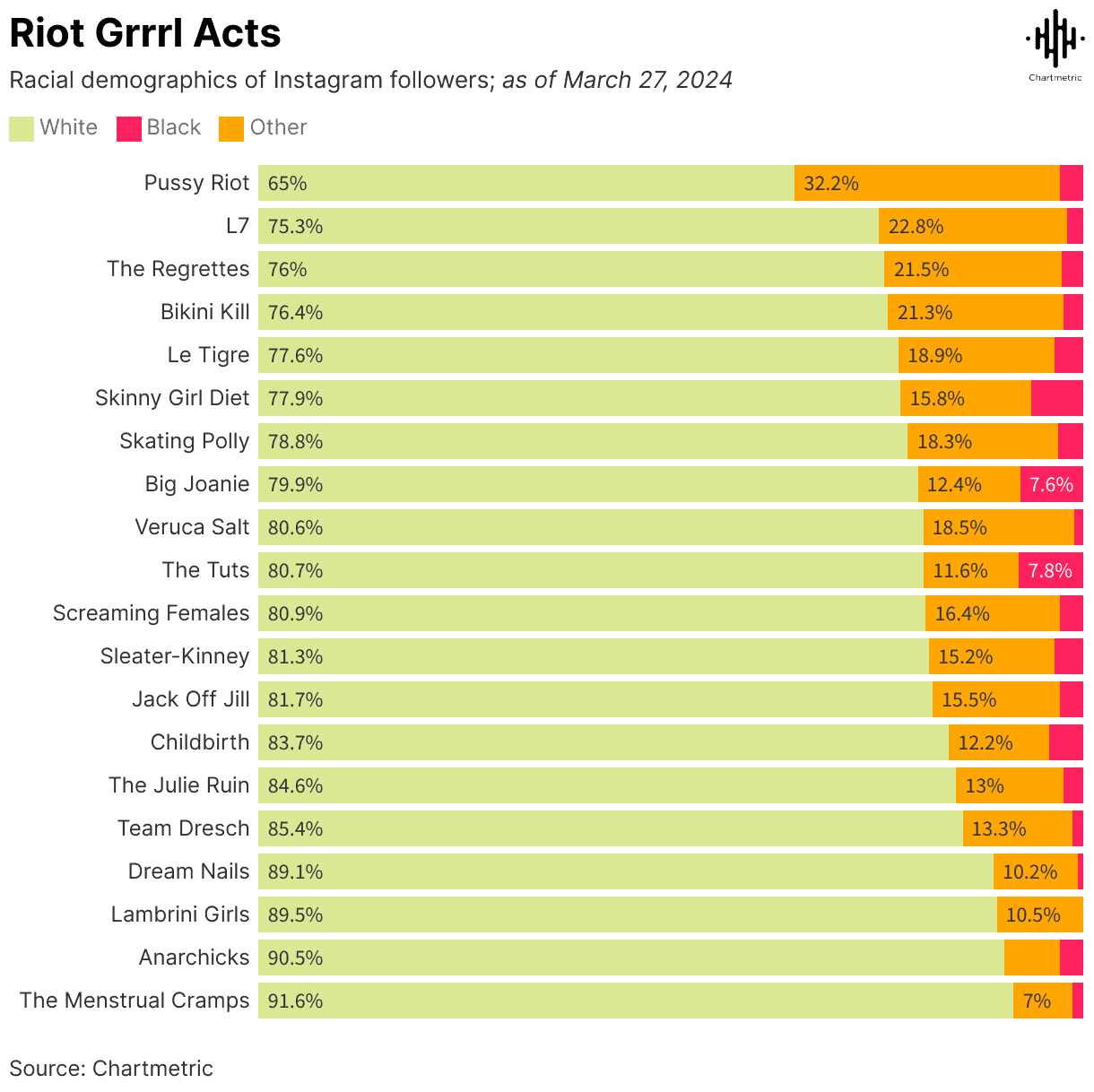

“Riot grrrl calls for change, but I question who it’s including,” Gunk zine writer Ramdasha Bikceem queried in 1993. “I see riot grrrl growing very closed to a very few i.e. white middle class punk girls.” Big Joanie are one such act who are helping to change this, opening up spaces previously deemed out of bounds for feminist rockers of color. The London-based trio have supported Sleater-Kinney, signed to Thurston Moore’s label, and earned rave reviews for their debut album Sistahs since forming in response to the rock scene’s lack of intersectionality in 2013.

Still, by describing themselves as “The Ronettes filtered through 80s DIY and 90s riot grrrl,” they seem more than happy to be mentioned in the same breath as the latter scene’s almost exclusively Caucasian lineage. Unsurprisingly, their audience is slightly more diverse than the norm, too, with 7.6% identifying as Black, a fairly higher share than most of their peers.

Also signed with the label are Shooting Daggers, a London-based queercore (a punk offshoot largely focused on issues faced by the LGBTQ community) band whose Spanish, Italian, and French heritage is giving the renaissance a pan-European flavor. “Reading books/watching movies about riot grrrl and the US Punk, HxC scene in the late ‘80s/’90s just showed me that you can go far and huge and be heard – starting from literally nothing but your ideas,” lead singer Sal Salgado Pellegrin, who co-founded the group in 2019, explained in a chat with KNM Presents.

Funnily enough, the newest perception-challenging band that is most resonating with riot grrrl fans is an entirely fictional one. We Are Lady Parts, the acclaimed British sitcom about Lady Parts, a loud and proud, all-Muslim, all-female group, has spawned an original EP in which all six tracks have racked up over 100k Spotify streams each, with the most popular track, “Fish and Chips”, recently hitting 400k. In comparison, Lambrini Girls’ most streamed tune, “Boys in the Band,” has 377k streams, still more than the 317k of “Happier Still,” the most popular song from Big Joanie’s 2022 sophomore album, Back Home.

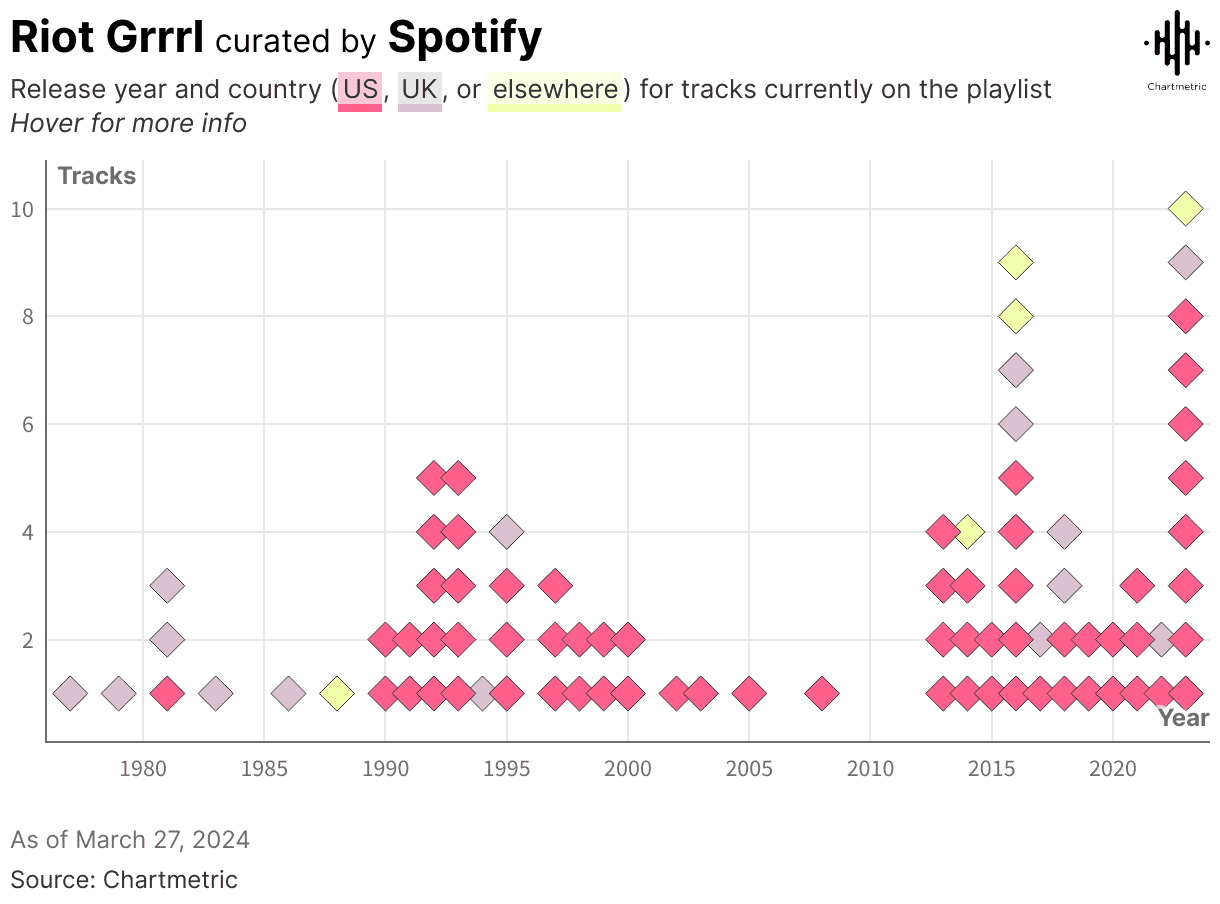

Of course, the very real riot grrrl revivalists don’t have a Rose d’Or-winning, internationally aired TV show to promote their wares. In a genre that is still very much a niche concern – Spotify’s official Riot Grrrl playlist has a respectable yet hardly earth-shattering 146k followers – anything that even approaches the six-figure mark should be classed as a win (even though a majority of the tracks on this playlist have over a million streams, these are the standout tracks from over three decades of the genre and are outliers from the norm). Interestingly, the UK is the second best-represented country on the aforementioned and predominantly American-based playlist, with 15 inclusions compared to the one-a-piece for Canada, New Zealand, and Russia, or the two tracks from Australia.

Other burgeoning acts who have already joined this 100k stream club include Problem Patterns (“Big Shouty,” 208k Spotify streams), the Hanna-championed Irish four-piece renowned for their merry-go-round approach to both lead vocals and instrumentation, PUSSYLIQOUR (“Pretty Good for a Girl,” 124k), the queercore favorites whose song titles alone are enough to make even Megan Thee Stallion blush, and M(h)aol (“Gender Studies,” 228k), the Dublin outfit whose feminist credentials start with the fact they named themselves after a 16th-century Irish pirate queen.

The latter are one of the more vocal fans of riot grrrl’s first wave, with co-founder Constance Keane telling Chartmetric:

“In my late teens, I was particularly inspired by Tobi Vail, drummer of Bikini Kill, among many other things. I found her approach to DIY culture really empowering and inspiring, and it’s something that I definitely considered during the beginnings of M(h)aol.”

Vail’s bandmate Hanna also had quite the impact, too. After watching Hanna’s documentary biopic The Punk Singer, Keane and singer Róisín Nic Ghearailt even shaved their heads in tribute. And, drawing upon their degrees in Gender & International Relations and Cinematography, the members of M(h)aol (ironically pronounced male) are addressing everything from rape culture and period sex to the legacy of the Magdalene laundries in similarly confrontational style.

However, it’s Hastings trio HotWax (“Rip It Out,” 462k Spotify streams) who are looking most likely to join the big leagues of British rock. Indeed, they have already broken out of rather scary-sounding playlists such as The Pit and screaming and onto more mainstream efforts such as The New Alt (1.1 million followers) and All New Punk (305k followers), and were also invited by Louis Tomlinson to perform at his Away From Home Festival in 2023. Who knows what the crowd of Directioners made of the act’s rage-fueled songs about contraceptive implants inspired by Hole’s Live Through This (“the thing that changed everything” remarked frontwoman Tallulah Sim-Savage about the post-riot grrrl classic she grew up listening to). But having graced many Ones to Watch in 2024 lists, the wider world certainly appears to be listening.

It could be argued that Dream Wife have already achieved such a feat. In 2018, the Brighton trio stole the show at Lollapalooza, while two years later they reached the UK Top 20 with sophomore So When You Gonna…, an album which — in still something of a rarity — was made with an all-female recording team. “The sense of community in the riot grrrl movement is something that we take to heart,” frontwoman Rakel Mjöll told Buzzlast year. “If you have a platform, you have to share it, however big or small it is.”

And Dream Wife’s social platform appears to be growing substantially, with the band amassing over 5.2 million YouTube views and 47k Instagram followers, and no fewer than five tracks with over a million Spotify streams, numbers which significantly dwarf those of their peers. In further proof of how riot grrrl is now being sold back to its country of origin, their Spotify audience’s has equal shares in the UK and US. What’s also interesting is the majority of their listeners, as is the case with those of most of their contemporaries, weren’t even born when the movement first started taking shape.

So why exactly does this sense of community appear to have significantly grown in Britain over the last few years? Could it be a response to the divisive political climate spearheaded by Brexit, the Tory government, and the media’s obsession with stoking the culture wars? Perhaps the #MeToo movement, which also opened up all kinds of conversations across the pond, has emboldened some to speak more freely about misogyny, abuse, and inequality? Might it also be a byproduct of initiatives like Girls Rock, the all-female summer camp which since 2016 has been teaching kids from eight to 18 the power of music?

Whatever the reasoning, it’s having a wide-reaching impact. Staged at London’s Southwark Playhouse in 2023, coming-of-age play Sugar Coat won rave reviews for its millennial spin on riot grrrl nostalgia. The Raincoats bassist Gina Birch felt compelled to release her solo debut that same year at the age of 67. Even Corinne Bailey Rae, the singer-songwriter best-known for the summery soul of “Put Your Records On,” was inspired to throw things back to her roots in riot grrrl band Helen on Black Rainbows, one of the more startling musical about-turns in recent memory.

“Don’t revive it, make something better,” Hanna once told the New Yorker, laying down the gauntlet to the new generation of bands hoping to follow in her riot grrrl footsteps. By channeling their anger, activism, and abrasive walls of noise toward more inclusive Gen Z themes, Britain’s latest musical invasion has undoubtedly fulfilled this feminist brief.

Visualizations by Nicki Camberg and cover image by Crasianne Tirado. Data as of March 27, 2024.