Learn how to mix live music and the essential gear and techniques every live engineer needs to know – straight from live veteran Toby Francis.

How To Mix Live Music: A Guide To Live Sound Engineering

by Toby Francis via Berlkee Online Take Note

The following information on live sound engineering is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Live Event Sound Engineering and Concert Production 101, written by Toby Francis, and currently enrolling.

A common saying in the field of live sound engineering is that sound reinforcement is a series of compromises: the fewer you make, the better the result. Learning how to create a great-sounding event involves eliminating as many obstacles and compromises as possible. Let’s take a look at some of the equipment that will bring out the sounds that enable you to make fewer compromises!

Power Amplifiers

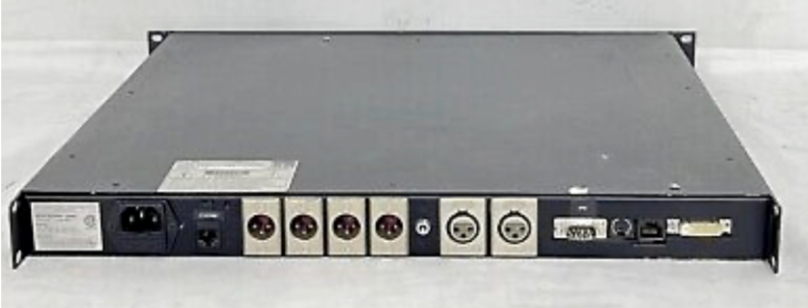

Power amps supply the speaker system with the power it needs to perform. They come in many sizes, in regard to output power. A power amp has an input which can be analog or digital, and sometimes they offer both for each channel as well as an output.

The input connector is usually a socket XLR and they accept line level. Sometimes they offer a plug XLR next to the input, which acts as a pass-through to be used in daisy chaining more than one amp together. This allows you to use the same signal to power more than one speaker.

The output of a power amp uses binding posts to connect the speaker wire to the amp. Since various types of connectors are used on speaker cabinets, panels with panel-mounted connectors are often mounted on the backs of amp racks with the bare wire leads connected to the binding posts on the amp.

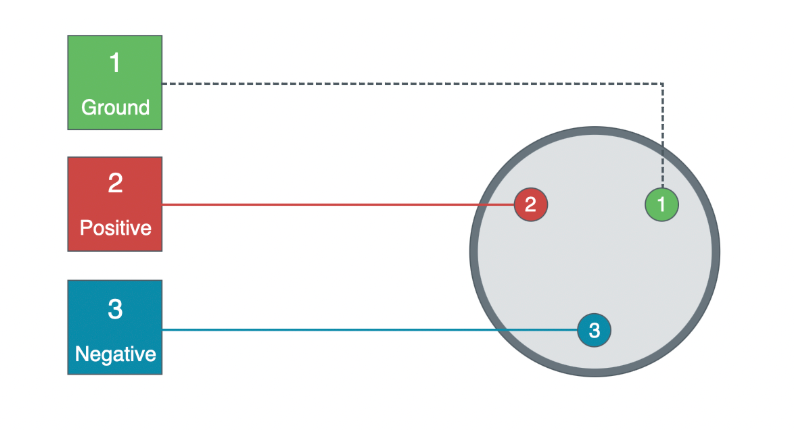

Power amps output both a positive (red) and negative (black) output. The positive leads go to the positive input to the speaker and the negative goes to the negative speaker input, ensuring that the phase is maintained. We discuss phase throughout the 12-week Live Event Sound Engineering course, but what you need to know first and foremost about it is that keeping the system phase correct and all the speakers working together is very important.

If you place two speakers next to each other and power them with the same signal, both in phase with each other, they produce the same sound. Disconnect one of the speakers and you will hear a slight reduction in level. Now reverse the phase to the second speaker and reconnect it and you will hear a great reduction in level, which is very noticeable when you listen from between the speakers. As you move your head from side to side you will hear a big change in both the level and frequency response. This happens because if the sound level is equal and the two speakers are out of phase, they are canceling each other out. A big part of sound engineering is identifying and eliminating as many phase issues as possible.

The power rating of power amps is listed in different impedances. Most amps will function with an impedance between 2 ohms and 16 ohms. The lower the impedance, the higher the wattage.

Crossover Systems

Speaker systems are generally composed of components that reproduce the different frequency ranges. Cone speakers come in various sizes: some reproduce low frequencies better than others but they don’t reproduce high frequencies efficiently. In this case compression drivers—mounted on horns which reproduce high frequencies, but not low frequencies—are used to complete the frequency spectrum. A crossover network divides the signal between the cone speaker and the compression driver. There are both passive and active crossovers.

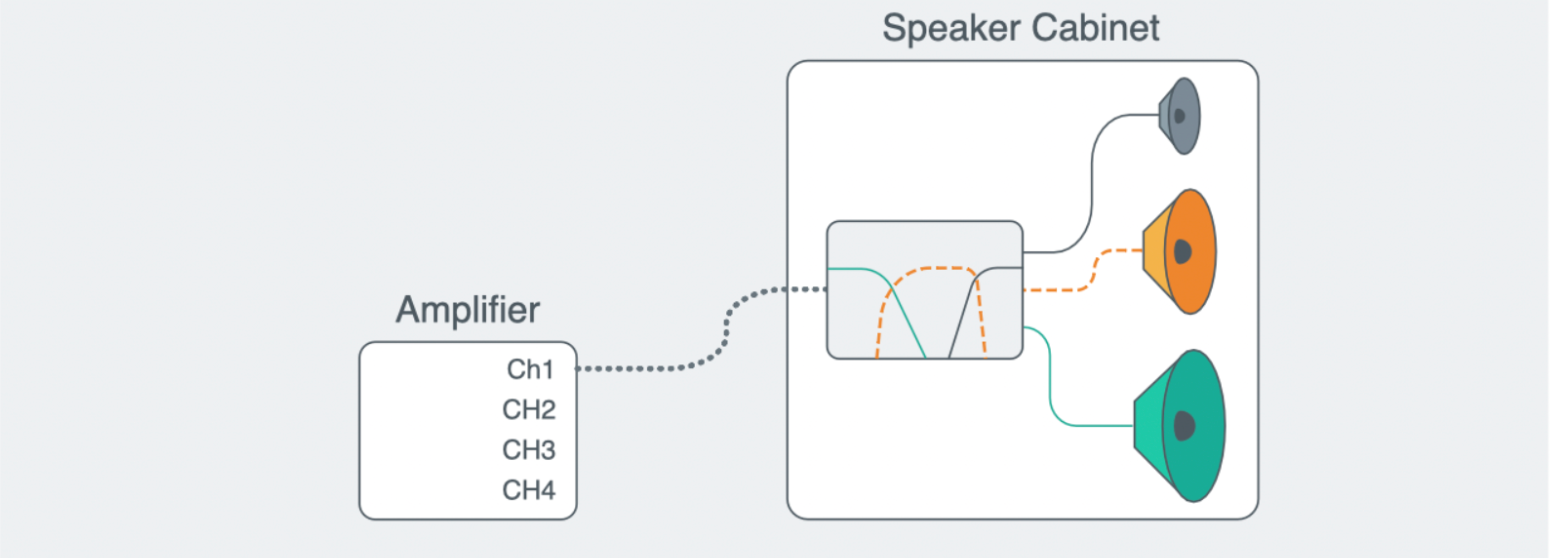

A passive crossover is placed after the amplifier output and divides the signal between two or more speakers, each outputting a different frequency range.

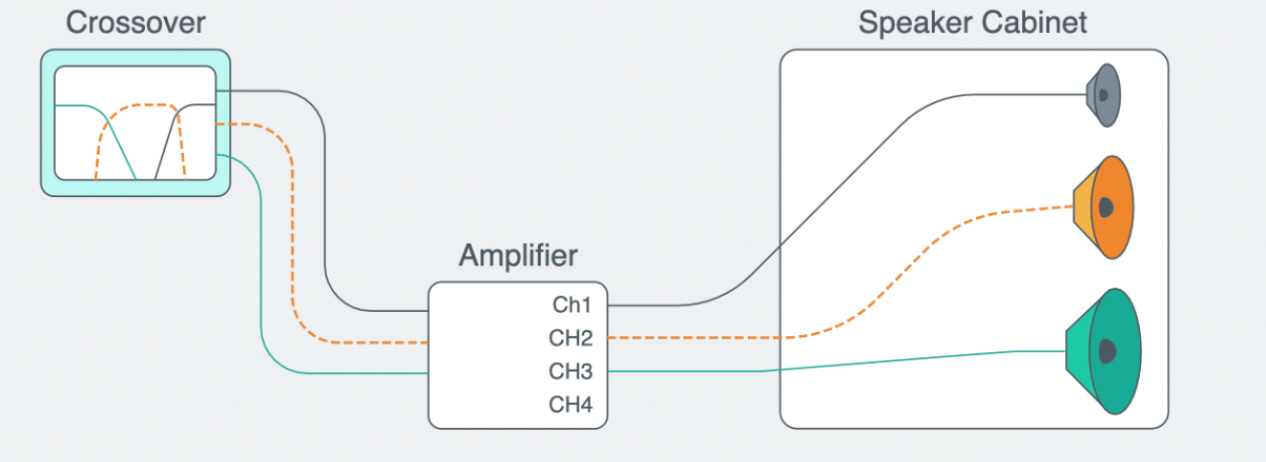

Active crossovers are placed before the power amplifier. Therefore, active crossovers deal with line level signals. When using an active crossover network, separate amplifier channels are required for each driver or set of drivers.

The crossover has an input and an output for each section you are trying to create. The input signal is full range; it is then divided at whatever the desired frequency or frequencies.

- A two-way crossover splits the input signal into two outputs, high and low.

- A three-way crossover divides the input signal into high, mid, and low.

- A four-way does high, high-mid, low-mid, and low.

By dividing the signal and sending each frequency band to a speaker component that is designed for that range, you increase the fidelity and efficiency of the speaker system.

Crossovers give you level control over the input into the crossover and the output level of each output band. This helps you balance the levels of each section of the speaker system.

Many of the new power amps have DSP internally so they can function as the crossover as well as the power amplification. This is common on the multichannel amps that are used in most of the newer systems.

In larger modern PA systems, the drive system, which is usually software-based, acts as your crossover. The multi-channel power amplifiers have onboard DSP, which gives them the ability to internally divide the signal into high, high-mid, low-mid, and low. All the amplifiers are networked together and a laptop or tablet is used to control the entire system. Once you are at a stage where you are using larger systems, networking skills using both cable and WiFi networks become very important. With really advanced systems like d&b’s GSL/KSL system, each speaker cabinet is powered by a separate power amp. This gives us the ability to control every part of the system independently as well as together. That coupled with their Array Processing software package gives you the ability to allow for room characteristics, which greatly affects how the room responds to the sound system. It tailors each section of the system to optimize coverage while avoiding unnecessary reflections and areas where the system is underperforming or overperforming.

Cables: Input Cables

We use many types of cables and connectors in live audio. Cables have both plug and socket ends, making it possible to connect them together to add length. Let us break them down into different types:

- input cables

- speaker cables

- multi cables

- power cables

- computer cables

- digital audio cables

Input cables can be analog or digital. Let us start with analog input cables and all the different connectors used. The standard microphone cable is the most common input cable. It has a three-pin XLR connector and is used to connect microphones to the mixing console. Analog signals can be MIC level or LINE level. MIC level is used for microphones or direct boxes, which are used to connect instruments to a mixing console. MIC level requires a preamp to amplify the signal. LINE level is a stronger signal, the output of a mixing console is LINE level.

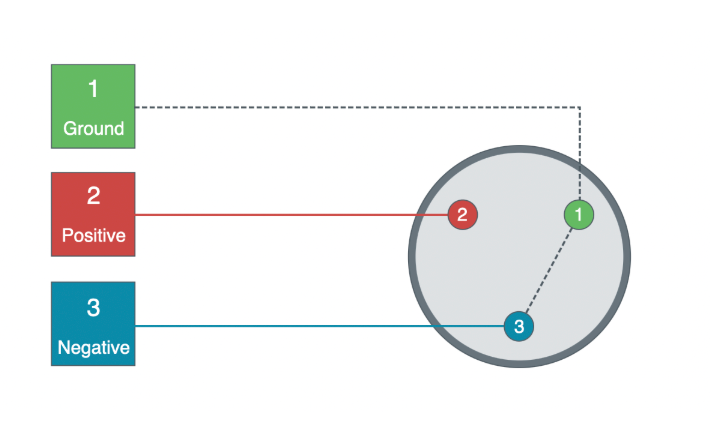

Here’s a diagram for a balanced XLR connector as seen from the rear (plug). There is a positive and negative, which must be maintained to avoid phase issues. If the positive and negative were reversed and the cable was not marked as a phase reverse, you would be potentially causing phasing issues.

Here’s a diagram of an unbalanced XLR plug from the rear. The ground and pin number three are tied together.

Microphone cables come in different lengths and should never exceed 300 feet, because the signal will diminish and the noise level will increase at long distances.

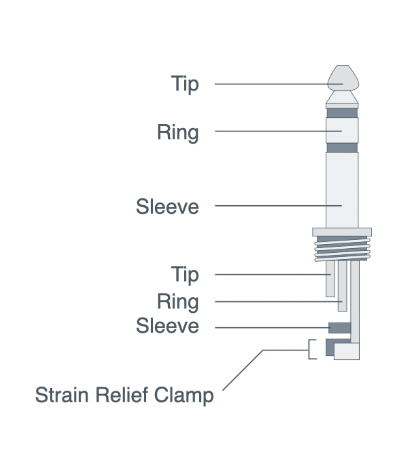

Mic cables can also be used for LINE level signal as well. LINE level is a stronger signal, so it will travel long distances without any reinforcement. Often a quarter inch, with a ring, tip, and sleeve, it is also used as a line level cable. A common guitar cable is sometimes used in pro audio situations. A guitar cable is a two-conductor cable and is unbalanced. A TRS or tip, ring, and sleeve cable is similar but has three conductors and is balanced. The polarity or phase must be maintained to avoid any unwanted phase issues.

Here’s a diagram of a TRS cable.

The tip is the positive, the ring is the neutral, and the sleeve is the ground.

Cables: Speaker Cables

Speaker cables come in several types ranging from single-channel cables (one positive and one negative) and can use any type of connector from a quarter-inch (guitar connector) to terminal connector.

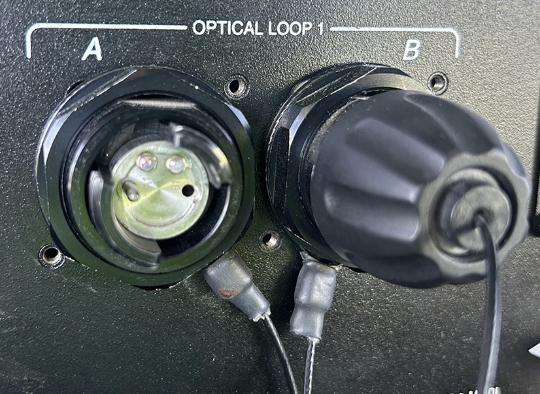

Many of the newer speaker systems use multi connectors like the EP4 or 6 or one of the Neutrik connectors.

These multi-pin connectors are preferred as they are easier and make the high, mid, and low connections more accurate. If you connect the amp from the low end of the system to the high-end component, it can cause damage to the compression as they are not suited to reproduce low frequencies.

Cables: Multi Cables/Snakes

Multi cables are cables that provide several cables within one jacket. They are sometimes referred to as snakes or multicores. A snake is used to feed the stage inputs to the mixing console, which is often in the audience area far from the stage. A 32-pair snake will give you 32 microphone lines within one cable. A 48-pair would do 48 mic lines.

Sometimes these snakes are outfitted with multi-pin connectors, which allows you to make one connection to connect several lines. This saves time and reduces mispatches.

Cables: Digital Audio Cables

There are several standard digital formats, such as Dante, which uses standard CAT5 cables, and MADI, which can use Coax cable. Many of these formats offer the ability to convert to fiber optic cable which can carry the digital signal very long distances through a very small piece of fiber optic cable. One Dante cable can carry 256 channels of audio through one CAT5 cable.

Digital audio has become the preferred media to work in as it is the most versatile and can travel long distances without signal loss.

AES is a digital format which also uses the same XLR connectors but requires a different type of cable. They are often marked or a different color than standard mic cables. AES will travel more than 300 feet and is one of the most common digital formats.

Other digital formats include MADI, which uses either coax cable or optical MADI, which uses a fiber optics cable. Dante is another digital format that uses either CAT5 cable or fiber optic cable for long cable runs. There are also S/PDIF and light pipes, but these are generally used in consumer-level audio devices.

These are just a few examples of the equipment you’ll need to make a room sound good, and it’s really only the beginning. In the full 12-week version of Live Event Sound Engineering you’ll learn all the basics needed to run a live sound event in 100- to 1,000-capacity venues. We’ll get into details such as mic placement for singers and musicians, and the different types of speakers and monitors that are out there, and which ones are best for the size of the room you’re working as well as how to mix a live show. Now that you have a bit of an understanding of what equipment you need, let’s conclude with a few of the important rules for how you work with that equipment.

Understand that electricity is very dangerous to deal with: Safety first! Alway check the power with your voltage meter, confirm you have an earth ground, and that the voltage is in the acceptable range (110–125 volts).

Understand that you must have enough power for your PA system: To avoid show-stopping power issues, it’s best to confirm during sound check that you indeed have enough power for your needs.

Understand power amps and crossover systems: You have to fully understand how your crossover functions and is set properly. The same goes for your power amps. It’s very difficult to troubleshoot what you are not familiar with. So it’s good to know as much as possible about what amps are powering what speaker cabinets. Labeling is also a big help when trying to trace a problem to its source.

Understand that you can’t be overprepared: There are so many different cables and adapters used in live sound, so making sure you have everything you need for a show requires you to think and plan ahead.

Live sound engineering is a complex craft that demands a deep understanding of equipment, systems, and safety. Every venue, every show, and every audience presents a new challenge, but by mastering the tools and principles of this field, you’re equipped to rise above compromises and deliver an unforgettable sonic experience. Keep learning, stay vigilant, and trust in your preparation—it’s the key to bringing your vision to life, one show at a time.