5 Lessons From Rick Rubin’s “The Creative Act: A Way of Being”

By Jeff “H” Harrington of Release Your Song

Rick Rubin is one of the most successful music producers in history. He has produced albums for Run-D.M.C., LL Cool J, Public Enemy, Slayer, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Adele, Ed Sheeran, Lady Gaga, Johnny Cash, Tom Petty, System of a Down, Rage Against the Machine, the Chicks, and many more. Whew!

A lesser-known album, but a personal favorite, is Krishna Das’s Breath of the Heart.

His first success came in the early days of hip-hop, when he was still living in his college dorm. As one example, it was his genius vision that brought Run-D.M.C. and Aerosmith together for their 1986 version of “Walk This Way.” He instinctively knew that that was a way of making hip-hop understandable to the masses.

The book I’m discussing here, The Creative Act: A Way of Being, has been quite successful, as has his podcast, Tetragrammaton. Clearly, he’s a brilliant guy who can seemingly do no wrong.

And he has a Substack!

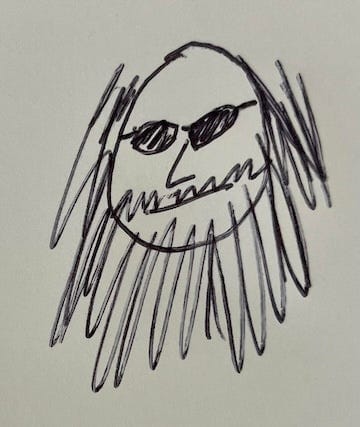

Rubin has always been a mystical figure, in part due to his expansive beard and his frequent donning of sunglasses. However, if you read his book or interviews with him, you will see that he is, indeed, a deep, mystical human being, and you will get glimpses of the foundations of his almost continuous success.

When asked what he does as a music producer, Rubin told 60 Minutes, “I have no technical ability and I know nothing about music… I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like… [I’m paid for] the confidence that I have in my taste and my ability to express what I feel.”

So, he’s not the type of producer who focuses on technical details, such as adjusting microphones and preamps. He’s something a bit more metaphysical. Here are 5 lessons from The Creative Act.

(*Note: all quotes are taken from The Creative Act, unless noted otherwise.)

Make It for Yourself

“Measurement of greatness is subjective, like art itself. There is no hard metric. We are performing for an audience of one.”

And that audience of one is you. Try as we might, we really have no idea what our audience will like, so we might as well make the art just for ourselves. We might as well be authentic.

And anyway, leading an authentic life is a reward in itself. When we’re elderly and looking back on our lives, wouldn’t it be horrifying to realize that all the art we made was a lie? To realize that we never fulfilled our artistic potential?

This mindset also removes the pressure of “perfection” and “success.” If you’re only making the art for yourself, then you don’t have to worry about anyone else liking it.

However, as a bonus, this is your most likely path to success. As Rick Rubin once said on the School of Greatness podcast, “It turns out that when you make something truly for yourself, you’re doing the best thing you possibly can for the audience.”

Getting back to his book, Rubin puts it another way: “If you think, ‘I don’t like it but someone else will,’ you are not making art for yourself. You’ve found yourself in the business of commerce, which is fine; it just may not be art. There’s no bright line between the two. The more formulaic your creation is, the more it hugs the shore of what’s been popular, the less like art it’s likely to be.”

Distill Your Work to Its Essence

“Distilling a work to get it as close to its essence as possible is a useful and informative practice. Notice how many pieces you can remove before the work you’re making ceases to be the work you’re making.”

Thus, Rick Rubin prefers to describe himself as a “reducer,” not a producer.

He’s famous for helping artists strip away anything nonessential from their music.

His work with Johnny Cash is a good example of this. Many of the arrangements are sparse, which leaves space for Johnny Cash’s voice to be huge. Here’s an example of one of his Johnny Cash productions:

In music, the fewer instruments there are in an arrangement, the more huge each can sound.

Generally speaking, the hugeness is a result of each instrument being able to retain more of its low frequencies. Low frequencies require a lot of energy from the speakers, and so when mixing a song, it gets tricky to include low-frequency information from each instrument. Choices must be made.

Typically, the kick drum and bass guitar are allowed to retain most of their low-frequency information, while the low frequencies of most other instruments are carved away and discarded.

However, if an arrangement only includes, say, vocal, guitar, and piano, then each instrument will be able to retain most of its low frequencies, and each can remain huge-sounding.

This also applies to Rick Rubin’s aversion to reverb. Reverb is what adds space around instruments. Whether the reverb is inherent due to how the instrument was recorded (for instance, if the instrument was recorded in a large room with a more distant mic), or whether it is added in post-production, reverb can make an instrument sound like it’s in a specific space, such as a room, a cathedral, or a concert hall.

Here are some examples, for anyone not familiar with the concept of reverb. The first vocal phrase you’ll hear is without reverb (ie “dry”), the second is how it would sound if it was recorded in a large room with the microphone set back about 15’ from the singer (ie: a natural reverb), and the final vocal phrase has a large, digital hall-type reverb on it (added in post-production / mixing):

Rick Rubin is famous for using very little reverb in his productions, and this makes the instruments sound like they’re just inches from your face, and, once again… huge.

Additionally, a minimalist arrangement allows the most important instruments to be experienced clearly by the listener, in the same way that you don’t want to drown a nice piece of fish in an overly rich sauce.

And perhaps most importantly — a minimalist arrangement amplifies intimacy.

Minimalism exists in other art forms, of course — the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, the haikus of Matsuo Basho, and the architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe are a few notable examples.

Of course, minimalism is not always the way to go, but I would suggest that it’s always a good practice to try to remove as much as you can. This can be very difficult and painful, though!

Learn How to Assess Your Own Work

“Distraction is a strategy in service of the work.”

Let’s stay with the example of removing anything extraneous from your work. How can you decide what’s extraneous? You might have already been working on this piece of art for years. How could you possibly still retain any useful, objective perspective? How can you experience your work with the detachment of a random, normal person?

This right here — this seems to be one of an artist or producer’s ultimate skills.

This is the skill of constructive distraction.

“When meditating, as soon as the mind quiets, the sense of space can be overtaken by a worry or a random thought. This is why many mediation schools teach students to use a mantra. An automatic, repeated phrase leaves little room in the mind for thoughts that pull us out of the moment.”

“The mantra, then, is a distraction. And while certain distractions can take you out of the present moment, others can keep the conscious part of yourself busy so that the unconscious is freed up to work for you.”

And different activities can be used in a way similar to a mantra: “We might hold a problem to be solved lightly in the back of our consciousness instead of the front of our mind. This way, we can remain present with it over time while engaging in a simple, unrelated task. Examples include driving, walking, swimming, showering, washing dishes, dancing, or performing any activity we can accomplish on autopilot.”

This is an example from my life: a couple of years ago, I discovered an approach that works well for me. When I’m nearing the end of mixing a song (so, to be clear, the song has already been written and recorded, and it’s in the final polishing stage), I create a short playlist.

The playlist starts with one or two songs that somehow vaguely remind me of the song I’m working on. These are my reference songs, and they can be similar to the song I’m working on in any, or all, of these ways — overall sound, emotional feel, rhythmic feel, instrumentation, or any number of other aspects. (I don’t use reference songs until I’m close to being finished with a song, by the way.)

Then, I put on the playlist and do something to distract my mind lightly while I’m listening. I’m trying to be better about cleaning, so that’s almost always what I do. Sometimes I cook.

When I use this approach, I feel like I can finally listen “like a normal person.” I don’t get lost in detail. Only the important things stick out. When I’m done listening, I take a few notes for my next mix session. It’s a perfect level of distraction for my mind.

This is one of the most important skills I’ve learned as a musical artist.

Be Present and Open

“We are all antennae for creative thought… If your antenna isn’t sensitively tuned, you’re likely to lose the data in the noise. Particularly since signals coming through are often more subtle than the content we collect through sensory awareness. They are energetic more than tactile, intuitively received more than consciously recorded.”

Rick Rubin has been practicing transcendental meditation since he was 14 years old.

Transcendental meditation involves repeating a mantra and is typically practiced for 20 minutes, twice a day.

From a Rolling Stone interview: “I realized that the person I am was shaped by the experience of the years of meditation. I feel like I can see deeply into things in a way that many of the people around me don’t, or can’t… It allows me to be very present with the artists I’m with. I think TM has trained me to be a very good listener. It’s a big part of the job.”

So, if we become more present and more aware, our art will benefit. Meditation is perhaps the ultimate way to become more present, but other activities, such as walking, can also be helpful.

And there are various types of meditation, as you may be aware. Not all involve a mantra.

Being more present makes us more connected to our intuition. I wrote about intuition in my post about The Artist’s Way.

When I started meditating about 15 years ago, whole songs — lyrics and music — suddenly began coming to me, whereas in the past, writing lyrics was the final, often arduous task.

Meditation has also improved every other aspect of my life.

Submerge Yourself in Great Works

“… consider submerging yourself in the canon of great works. Read the finest literature, watch the masterpieces of cinema, get up close to the most influential paintings, visit architectural landmarks.”

Why should we do this? Rubin writes, “Broadening our practice of awareness is a choice we can make at any moment… To learn, and to be fascinated and surprised on a continual basis.”

It’s a way to fill up our creative well.

Of course, what you consider a masterpiece is up to you: “There’s no standard list; no one has the same measures of greatness. The ‘canon’ is continually changing, across time and space.”

And Rubin writes about another effect: “The objective is not to learn to mimic greatness, but to calibrate our internal meter for greatness. So we can better make the thousands of choices that might ultimately lead to our own great work.”

This is similar to the concept of the artist date, which I wrote about in my post on The Artist’s Way.

One thing I would love to know, regardless of your art form — have you found a way to get yourself into an objective state, similar to how I described using cleaning as a distraction when I’m listening to a song I’m working on?

Release Your Song is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.