________________________

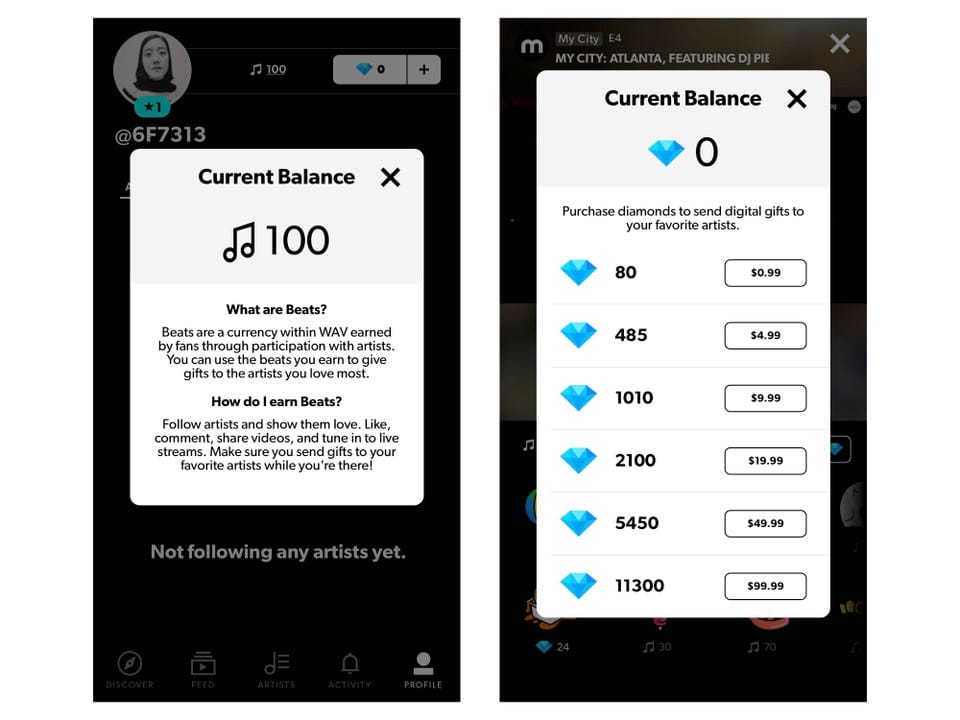

By Cheri Hu. This first appeared on Forbes.Speaking at the Cardozo School of Law on December 5, 2018, YouTube’s Global Head of Music Lyor Cohen made an argument that initially seemed frivolous, but actually rings with a deeper truth:“The music business used to be an audio business, and then it became an audiovisual business. Now, I think it’s going to become a visual audiobusiness.”Cohen didn't just switch around the words “audio” and “visual” for fun: the new economics of digital music and media arguably demand it.During its heyday in the '90s, MTV provided a valuable channel for major labels to shape the visual appeal of its biggest stars, from Michael Jackson to Madonna, but nailing that video placement was always secondary to driving record sales. Overall, during the "golden age" of recorded music in the last two decades of the 20th century, videos and live tours were often treated as advertisements for albums—prioritizing the commercial performance of the audio over that of the visual.Nowadays, it's the other way around. The margins on streaming are much lower than on physical purchases, and while major playlist placement can give featured tracks up to six figures of additional revenue, many in the industry have expressed disillusionment around the strategy's efficacy for long-term fan development. As a result, artists are increasingly incorporating video and other visuals not just into their creative processes, but also into their business models from the very beginning of a project, turning to captive audiences on the likes of Instagram, YouTube, TikTok and even Netflix for support.“Even though there’s nothing like MTV now, videos today are more important than ever, because everyone’s holding a smartphone," Dre London, manager of Post Malone and founder of London Entertainment, told me. “Most people worldwide immediately go to YouTube as soon as they hear a song they like. Videos get to show artists in a different light from a live show. And you have to capture it right, or else you end up having the wrong look out on the internet forever.”In fact, music plays a crucial role in convincing venture capitalists about video's potential for growing consumer businesses across the board. For instance, in a recent blog post about the future of consumer startups, Andrew Chen, General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz, writes that video is “the new technology at scale." To back up his point, he appropriately cites the fact that while it took the 2012 video for Psy’s “Gangnam Style” almost five years to reach three billion views, the 2017 video for Latin crossover hit “Despacito” accomplished the same feat in just one year.As the video-tech landscape continues to evolve and scale in 2019, so will the creative benefits and challenges it offers to the music industry. Below are four ways that the business of music videos will change this year, along the axes of aesthetics, delivery and monetization—with specific examples of artists who are already moving the needle.1. They will be livestreamed.At its most powerful, music fosters shared, emotional connections—whether virtually between an artist and a fan on a streaming platform, or in person between a full stage production and tens of thousands of fans in a stadium. For many artists, live events also comprise a more profitable revenue source than recorded music, as it can take a song up to a few years to recoup on its expenses in a streaming-first landscape (if it does at all).A-list artists are repeatedly making the case that their fans crave these shared events virtually as much as in person, especially if the artists themselves are in command of the execution. Kanye West used a relatively small live-streaming app called WAV to broadcast the release party for his album Ye, which catapulted WAV to the top of the Music charts in the iOS App Store. Ariana Grande attracted up to a record-breaking 829,000 simultaneous viewers to the live premiere of her music video for “thank u, next,” which she and her team orchestrated using YouTube's Premiere feature.One of the biggest opportunities in live-streaming revolves around the derivative ecosystem of content that can come from a given broadcast. In his blog post, Chen emphasizes the potential of “video-native” products, which he defines as “any product that automatically generates video when users engage.” Minimizing the amount of friction to video creation can encourage “more video-sharing activity, thus more viral acquisition and engagement,” writes Chen.Esports is a perfect example of a “video-native” product, in large part because of its vibrant livestreaming culture on platforms like Twitch and, increasingly, YouTube and Facebook. It’s no coincidence that a growing number of artists and record labels are partnering with esports companies to cash in on these naturally viral dynamics.Of course, music videos are by default "video-native"—and, at their best, highly meme-able—yet they have intersected surprisingly little with livestreaming to date, perhaps because the business model around the format remains relatively unsettled for the long tail of artists. While brands seem comfortable with one-off sponsorship opportunities for livestreams of larger events like Coachella and California Roots, the market for dynamic advertising against livestreams from more emerging artists and personalities is still relatively more freeform, even on the biggest platforms like Twitch.Aside from ads, another source of potential revenue in livestreaming involves direct contributions from users, in the form of pay-what-you-want donations or "tips"—a model that is already being normalized in some non-Western markets, and which is discussed in the next section.2. They will enable more financial support directly from fans.Crowdsourcing funds for music videos is nothing new. Platforms like Patreon allow artists to set up pay-what-you-want crowdfunding structures on a project-by-project basis, such that fans can contribute anywhere from $1 to $100 for each video an artist releases (see Amanda Palmer and Peter Hollensfor key examples).What is relatively newer in the music world is the concept of micropayments for videos, both during and after their release.When Chinese music giant Tencent Music filed to go public on the New York Stock Exchange, the company's financial statements revealed a surprising alternative business model compared to that of a standard Western streaming platform. Tencent made over 70% of its music revenue in Q2 2018 not from audio streaming, but rather from “social entertainment services,” including in-app monetary “tips” and other virtual gifts that users could send to each other. Many digital influencers across Asia and around the world treat these micropayments as a core income stream, potentially earning as much as 50,000 yuan per month from tips alone.On Western platforms, the micropayment economy is still young, and is often tied closely to live-streaming. Twitch viewers can purchase virtual gifts known as "Bits" for their favorite streamers, while select YouTube users can pay to highlight their messages during a given channel's livestreams (which includes the Premiere function that Ariana Grande used for "thank u, next") by purchasing "Super Chats."WAV is also experimenting with in-app currencies named Beats and Diamonds that fans can either purchase immediately or earn over time through social participation, then gift to their favorite artists regardless of whether or not they are livestreaming (screencaps below). Importantly, several music magazines, including Mixmag and The FADER, also maintain their own video accounts on WAV, and can attract financial support through these same micropayment mechanisms—a model that could be potentially game-changing for the future of music journalism.