__________________________

Guest post by Alex Wilson of Soundfly's Flypaper2019 will be the 20th anniversary of Sam Mendes’ critically acclaimed and controversial film American Beauty. Anyone who saw it back in 1999 will remember the way the storytelling captured one’s imagination with a very intellectual sort of seduction. American Beauty was and still is a filmmaker’s film, yet for those of us who care about film music, it was an utter game changer.You might be wondering why we’re examining a 20-year old-score today. Well, Thomas Newman’s music for American Beauty stands the test of time as a masterclass in film composition. It’s unconventional in tone and instrumentation, with its emphasis on tuned percussion having a lasting effect on music made for films, television, and even advertising. Moreover, Newman employs a variety of different compositional approaches to suit the demands of each individual scene while maintaining a sense of unity and emotional impact.This is a great time to mention that Soundfly is currently hard at work developing our own Mainstage course in film score composition, due to launch later this year. If you’re interested in being notified when the course launches, just sign up for our mailing list and you’ll be the first to know. In the mean time, we have loads of other online courses that might suit your interests, as well as a team of Soundfly Mentorsexperienced in composition and arranging!Now, while Newman is not as well known a composer as, say, Hans Zimmer or Ennio Morricone, he is no less a giant of his craft. The Newmans are one of the most accomplished musical families in recent American history. Randy Newman, one of the country’s most beloved singer-songwriters, is Thomas’ cousin and an accomplished film score composer in his own right. Thomas’ father, Alfred, was also a towering figure in early film scoring, cementing a legacy between the 1930s and 1960s that led to him being counted as one of three “Godfathers of film music.” The Newman family also boasts other successful composers in Lionel, Emil, Maria, David, and Joey.It’s probably no surprise, then, that Thomas Newman has been nominated for 14 Best Original Score Oscars, but frustratingly, has yet to land an actual statue. His score for American Beauty suffered the same fate, even as the film cleaned up in several other major categories. The film, which humorously and ruthlessly exposes the emptiness at the heart of America’s suburban dreams, might seem like it needed a score focused around disillusion and loss. But Newman cleverly opted for something a little different. His score is driven by Eastern-tinged tuned percussion, tribal drums, and a unique emotional tone that augments and densifies the film’s socially critical layers of subtext, rather than reinforcing them.Here, we’ll look at three of the most iconic cues from American Beauty, and how Newman subverts our expectations with each to heighten the viewing experience in various ways. There are short clips from the film in each section, but we strongly recommend rewatching the film in its entirety if you can. Newman’s score is so much more effective within the total, fictional world of American Beauty than it is disembodied on the soundtrack release. The basic cue transcriptions here have been lovingly provided by guitarist and composer Filippo Faustini.“Dead Already”

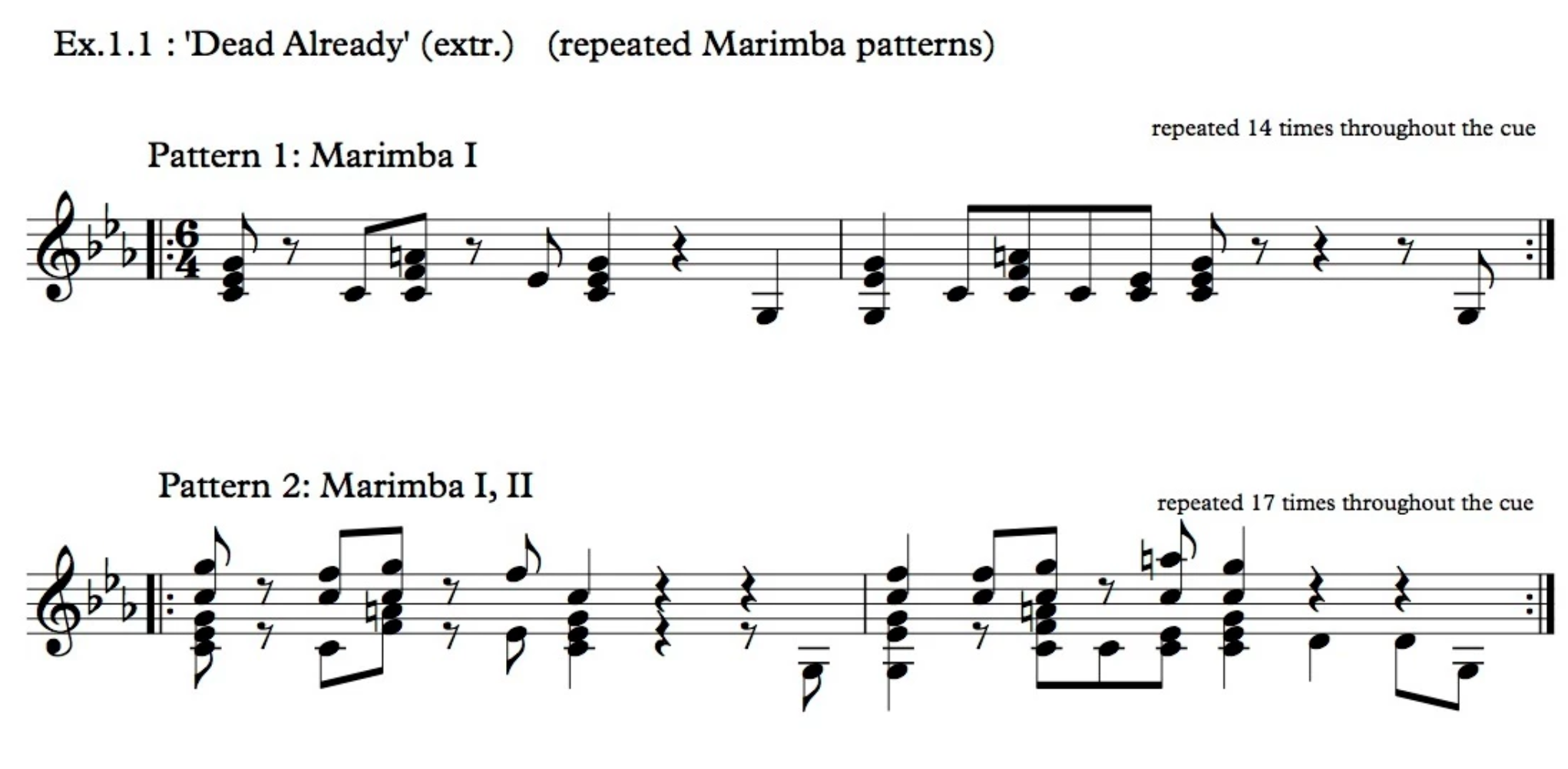

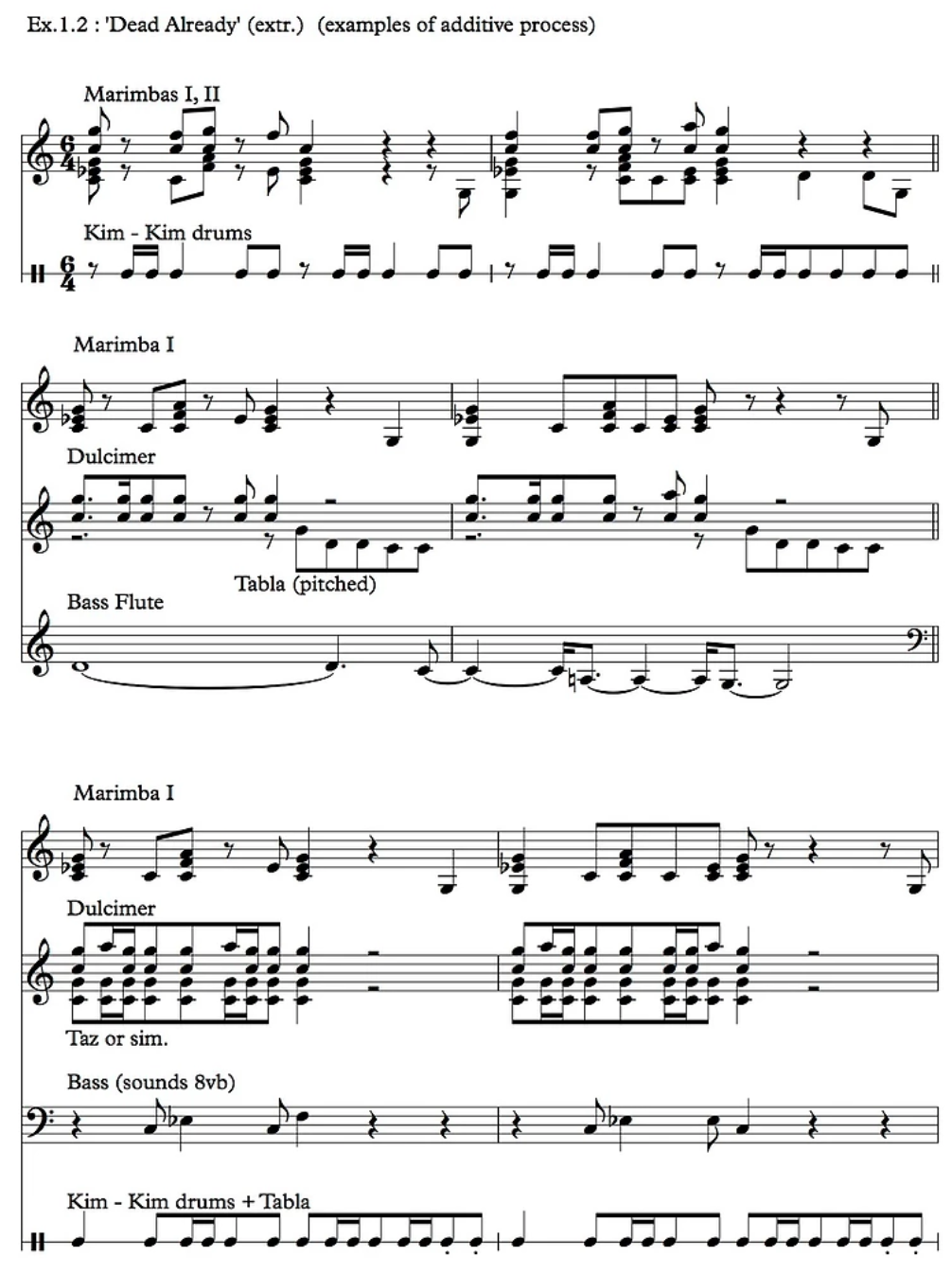

One of the first things you’ll notice is how the name of this cue seems to contradict the lightweight, sunny feel of the music. Its optimistic tuned percussion contrasts with the depressed monologue of protagonist Lester Burnham, yet it sets the scene perfectly alongside the brightly colored roses scattered around the frame. As we’re drawn deeper into his bleak outlook, “Dead Already” intensifies its jauntiness. Acoustic guitar strums, small drums, and some well-placed bass guitar notes only highlight the distance between Lester’s actual existence and the implied American dream that he should be living, which reveals itself as a sinister anxiety just beneath the surface.

“On Broadway”/“Root Beer”

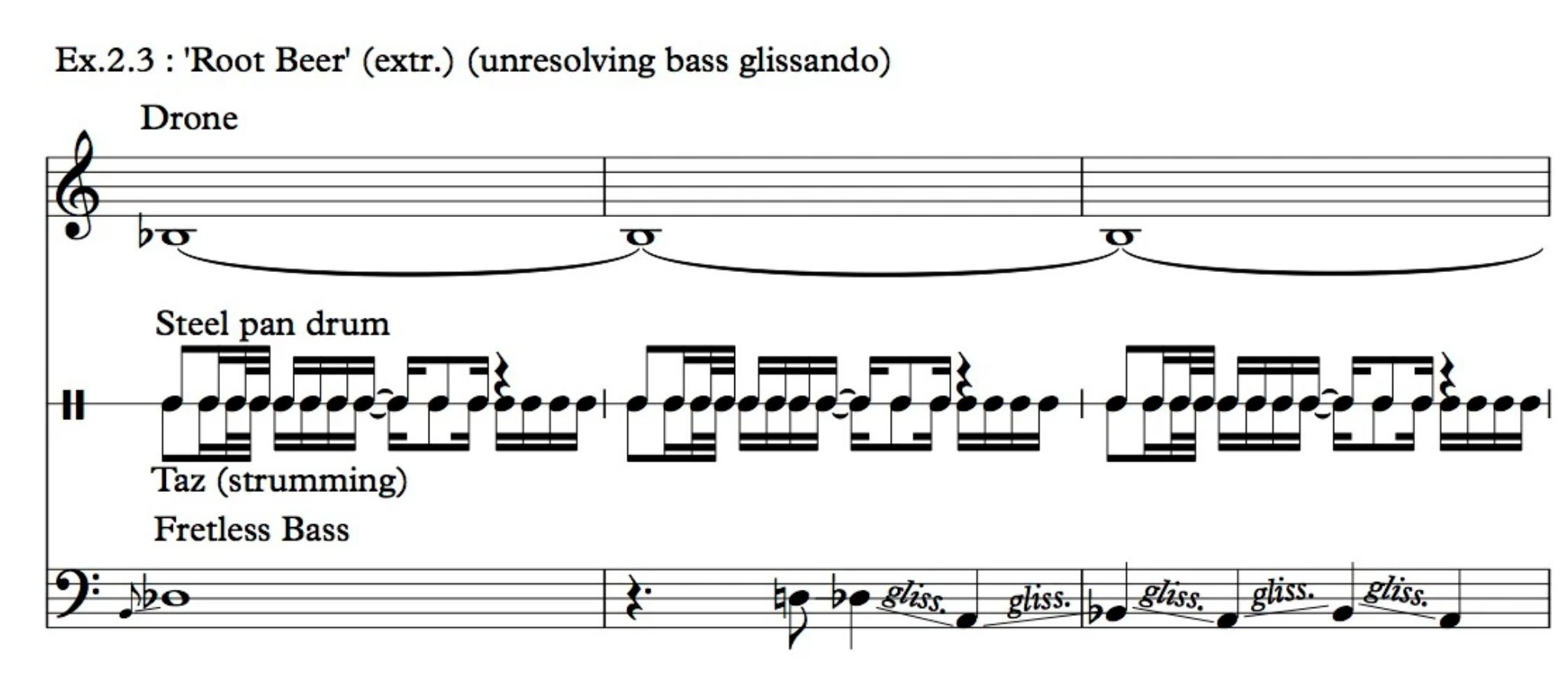

Now, here’s an example of a musical contribution from Newman that opts to stay closer to the surface. His cue, “Root Beer,” weaving in and out of the 1960s standard “On Broadway,” feels more like sound design than straight musical composition, per se. He employs frantic tribal percussion and atonal ambient noises to evoke the lustful dreamscape of Lester’s mind.What’s fascinating about this cue is the way that it structures the sense of time within the film world. One of the key concepts in film is diegesis. Any sound or music that occurs in the world inside the film, that the characters can likely hear themselves, is diegetic, while music and sound that is used as part of the decorative telling of the story, and which is therefore not heard or experienced by the characters, is non-diegetic. Most film music is non-diegetic (e.g., if you’re out on a boat hunting a giant shark, you’re probably not hearing a string ensemble).Yet this cue blurs those lines. “On Broadway” is most certainly being performed within the film world, but when we fully enter into Lester’s own consciousness, that music fades away and is replaced by the sensual, exotic sonic oasis of his fantasy. We follow Lester as he leaves his bodily reality in the gymnasium, and journeys to a wholly other mental reality with a new set of contours. What counts as diegetic and non-diegetic here is purely subjective based on which character’s perspective we choose to occupy.

“American Beauty”

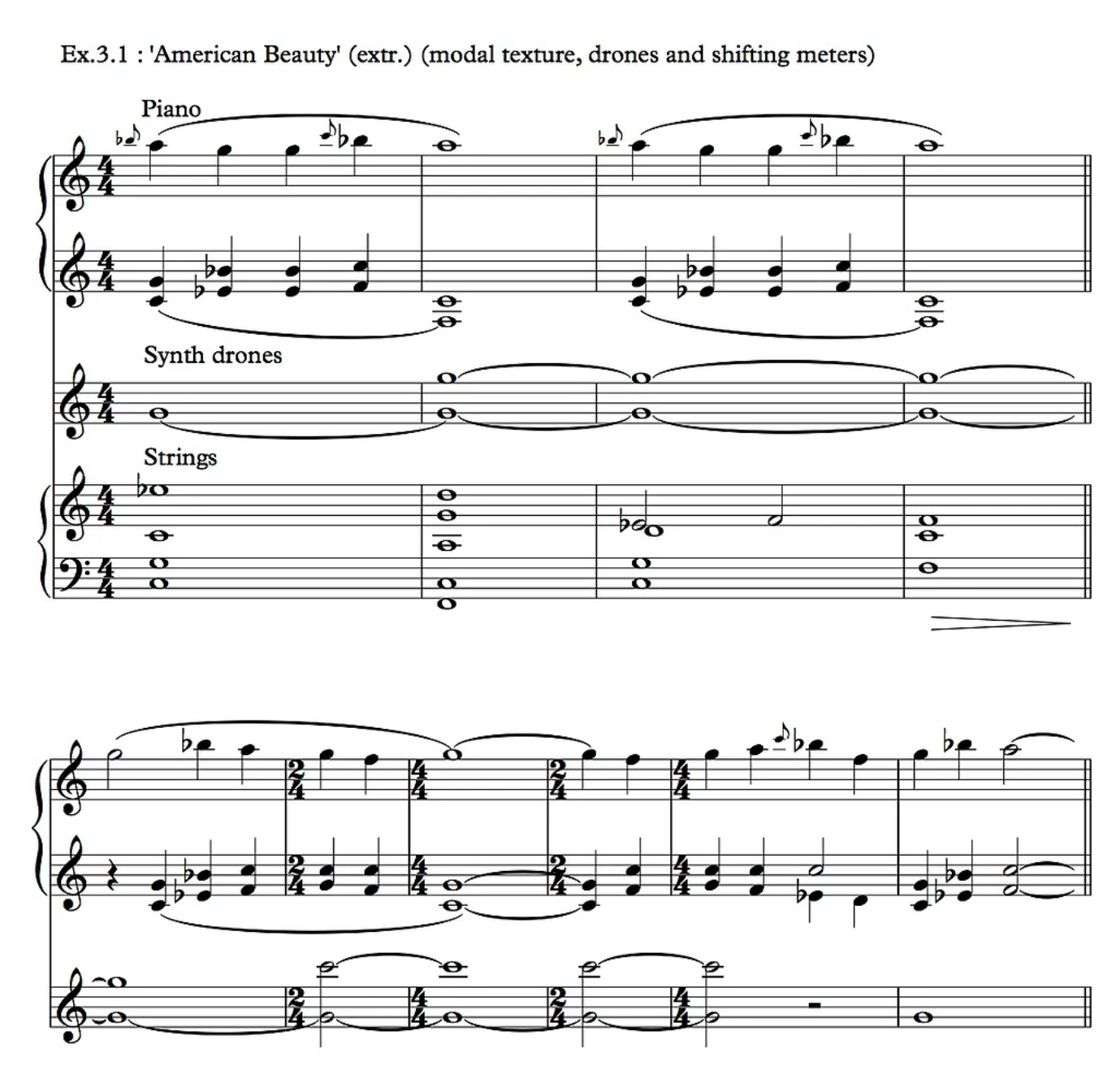

Of all the cues here, “American Beauty” (reprised at the film’s end as “No Other Name”) stands on its own, without explanation. It’s the most famous cue from the film and a gorgeous piece of music in its own right. The unresolved melodicism of its gentle piano recalls the work of minimalist composers like Brian Eno and Arvo Pärt, while the gentle bed of synths borrows from the best of the new-age color tone palette.