In an effort to assess how different labels fared during the industry transition to streaming, the good people at Chartmetric breakdown different trends of music from the past three years across seventeen different markets.

________________________________

Guest post by Josh Hayes of Chartmetric

To vet how labels fared through the streaming transition, we tracked the trends of chart-topping tracks over the past 3-years and across 17 music markets. Below we discuss the most interesting, and most informative, results.

“Man the walls! The waves of the digital streaming revolution approacheth!” (Photo Credit: Giuseppe Famiani)

To wrap up the decade, many of us at Chartmetric have spent time looking back at the whirlwind that the music industry just went through. The 2010s saw radical growth in the revenue and membership of music streaming platforms. In turn, that has changed how music is made, marketed, and consumed.

The growth in streaming has allowed the major labels to bring in massive amounts of revenue, but their growth seems to be slowing.

But as big as they are, the Western recorded music industry is much more than Universal, Sony and Warner. There have always been huge independents like 300, Concord and Beggars Group operating in the space. WINTEL’s 2018 report, a product of MIDiA and Music Ally, showed the independent sector gaining much ground (and asking the key question of whether industry analysis should count ownership or distribution revenue as the basis of evaluation).

To vet how either fared through the streaming transition, we tracked the trends of chart-topping tracks over the past 3-years and across 17 music markets. Below we discuss the most interesting, and most informative, results.

Regional Analyses of Charts

We use the Billboard Hot 100, Spotify Top 200 Daily Chart, and the Apple Music Top 100 Chart as our barometers. We follow the digital charts back to the earliest days of their inception. For Spotify that is in 2016 and for Apple Music that is mid-2018. Billboard only offers a global chart, while both Spotify and Apple have region-specific charts and therefore we can use those to dig into specific countries on those platforms. (Sidenote: If you look at multiple charts per day/week, over a couple years, and across numerous countries it turns out you get to 1.7M data points pretty fast!)

If you’re interested in the methodology, you can click here to zip down to and check out. Here are some crucial points:

- We collapse all tracks into one of two categories: “Major Label” or “Non-Major Label” Major label refers to one of the “Big Three”: Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group.

- We purposefully use the term “Non-Major” as opposed to “Independent/Indie/DIY”, which have each taken on their own definitions, depending on whom you ask. This framework is temporarily created to allow for an easier-to-understand binary analysis, despite acknowledging a far more complex business environment in 2019.

- We include any of Sony/Universal/Warner’s owned and operated companies to be a part of the “Majors.” So a release under Interscope, Columbia, Atlantic, etc. also count as releases by a “major label.”

- For “Majors,” distribution deals don’t count… If an indie artist or label only has a distribution deal through a major label then we call that “Non-Major.”

- …but joint-releases do. The number of differing types of deals negotiated between artists, publishers, rights holders, distributors, and record labels is truly dizzying. If we saw indications that a major label had a “significant” hand in a release, such as a joint-venture between two companies, then we erred on calling it for the “Majors.”

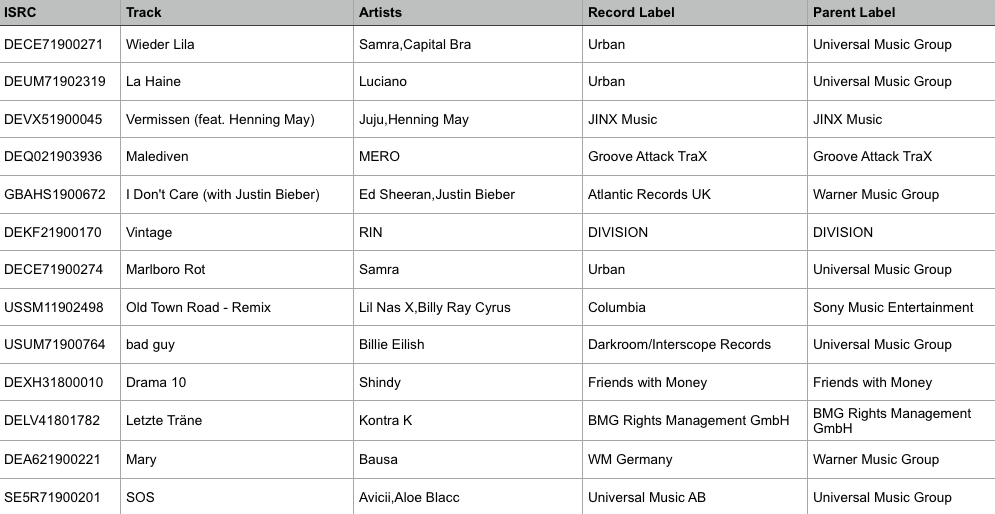

- Multiple releases and meta-data grey areas: Billboard and Apple don’t always offer label information for each track so we had to sync each track with our database. In some cases, a track would have numerous ISRCs which in turn had conflicting metadata. For each song, we gathered all record labels affiliated with that release. If any of the record labels were identified as a major label, then the track was marked as released by a “Major.”

Overall Global Trends

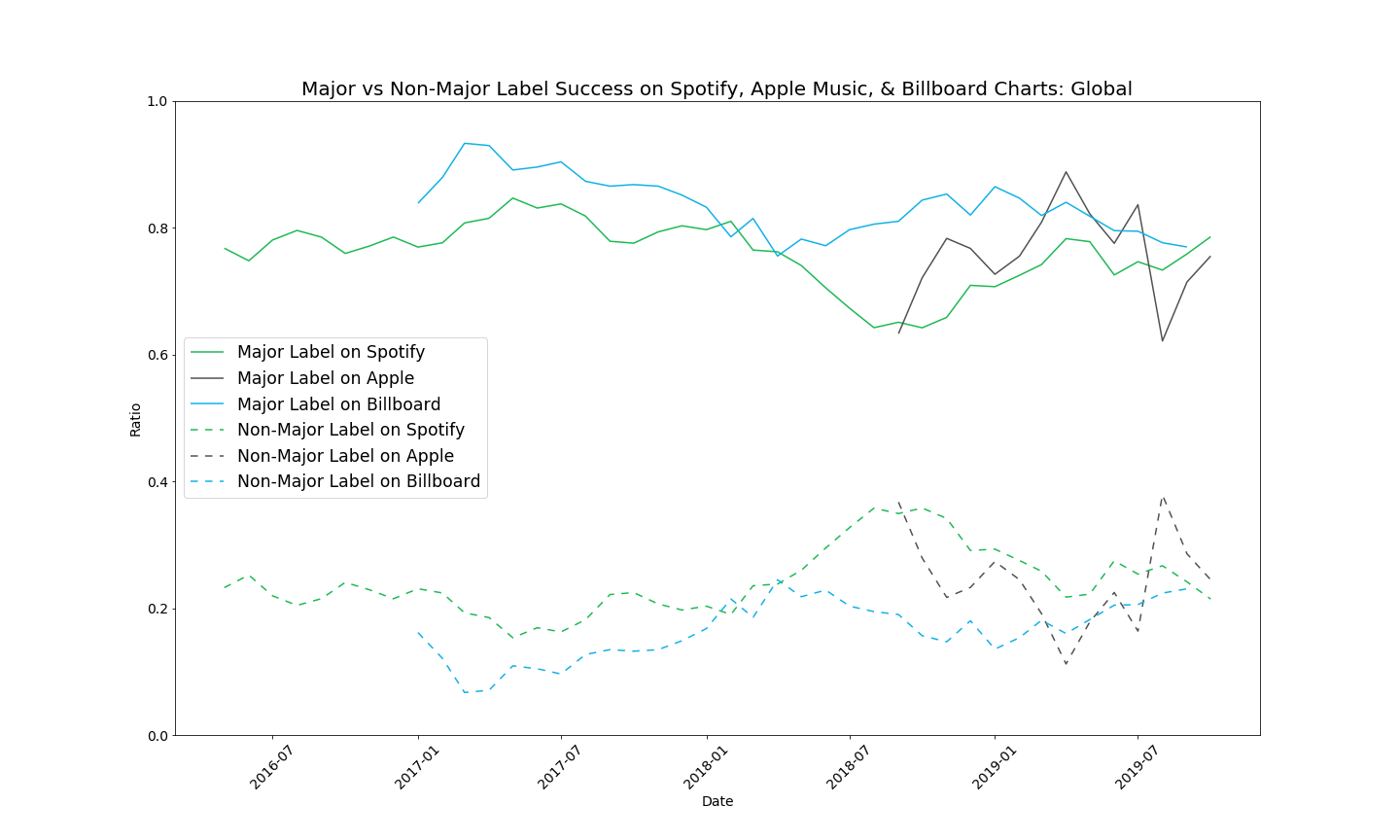

Billboard Hot 100 offers a weekly global chart while Spotify and Apple Music offer daily charts. We collapsed each chart into its corresponding month for comparison. Because Spotify is out of 200, and Billboard/Apple out of 100, we convert the data from absolute counts of chart-occurrences into the ratio of slots.

There is a lot to consider in the above graph. Here are a few of our key take-aways:

- If you were watching the Spotify charts in late 2018, you’d think the sky was falling for Majors. Non-Majors gained a lot of successes in a short amount of time.

- Billboard and Apple Music’s charts tend to favor the Majors more than Spotify’s charts.

Mexico, the new music landscape, is highly contested

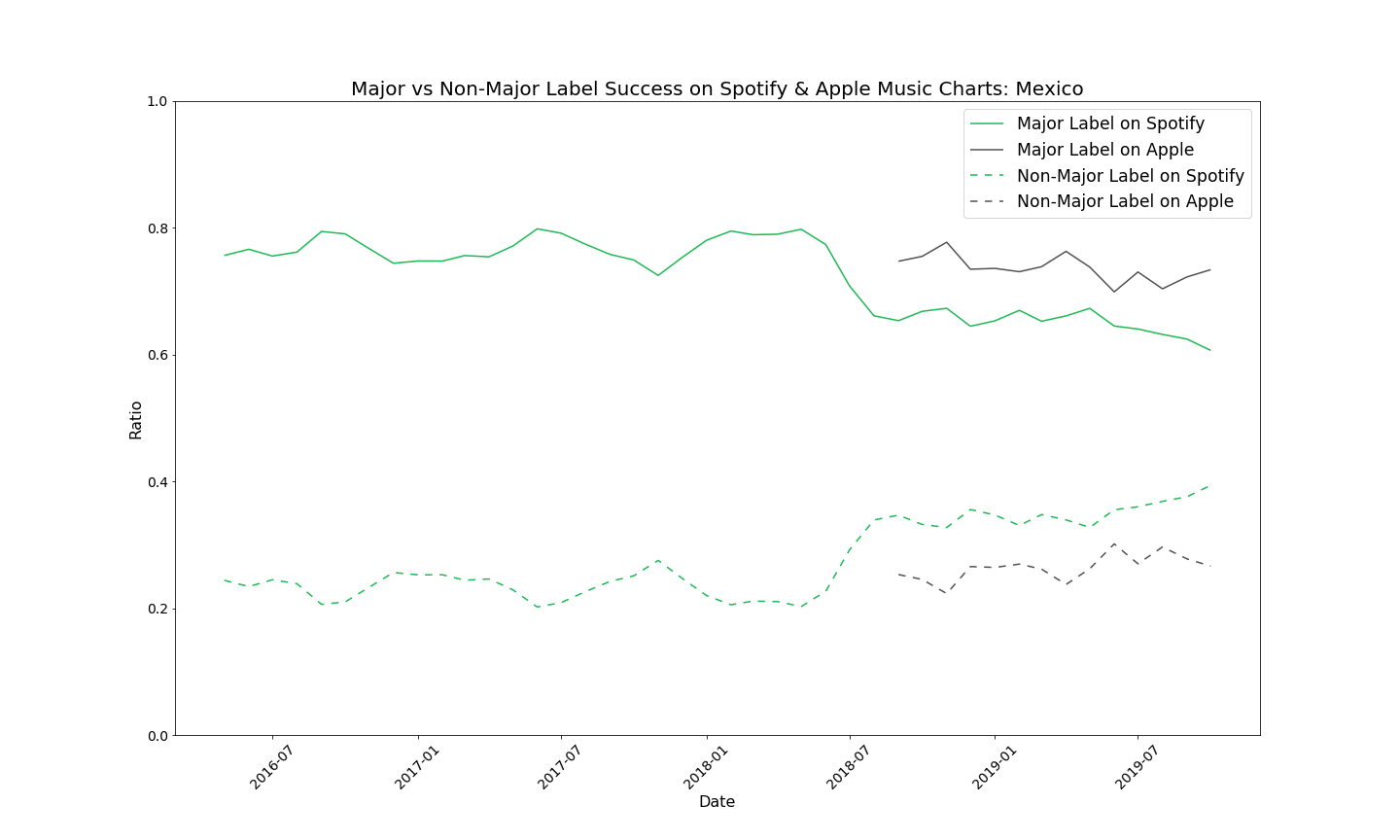

To get a general sense of how the regional-success of labels differs, one of the best examples is Mexico. Mexico only comes in as the 18th largest music market by generated revenue, so you might initially doubt it as the go-to example.

But don’t be fooled.

We’ve explained before that Mexico is a powerhouse of a music market and Spotify knows that Mexico City is the World’s Music-Streaming Mecca. Additionally, Latin America has shown the highest regional growth for four years in a row according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI).

While Mexico isn’t the most lucrative market, it may be the most responsive to, and indicative of, the changes of the new music-era.

So, let’s look at how much of the top charts have gone to Majors and Non-Majors, and then, we’ll go over a few takeaways:

Some things to notice:

- The trends seem pretty stable up until 2018, there is a period of significant change, and then the trends become stable again by 2019.

- Over the past three years, the proportion of chart slots that have belonged to Non-Major labels has increased from 24.4 percent to 39.4 percent. That’s more than a 60 percent increase in just three years. That is pretty significant.

- Apple Music charts reliably skew more towards major label releases than Spotify charts.

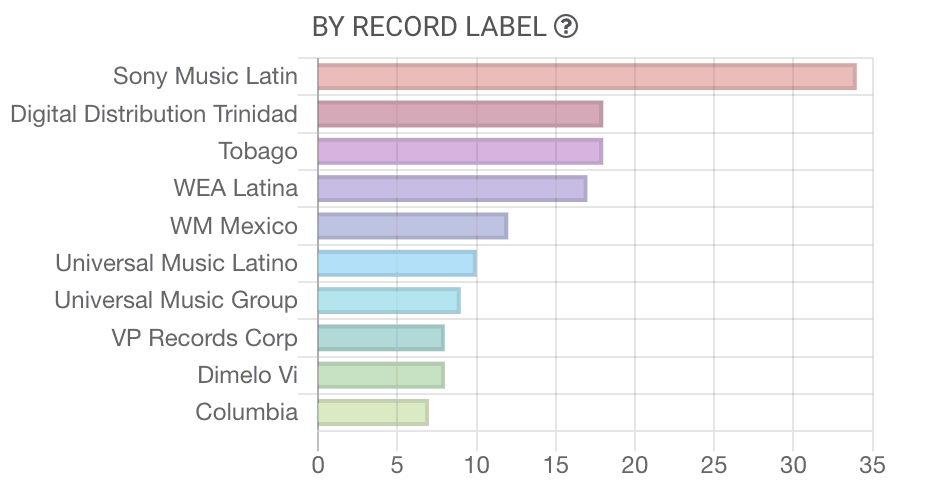

From June to December of 2018, the number of major label releases on the Spotify Chart dropped from 78.5% down to 63.5% – a full 15-points. By December, more and more charts spots were being claimed by Anuel AA, VP Records Corp, DEL Records, Banda MS, and Lizos Music which is “one of the most successful regional Mexican labels on the market today.“

But even by early-2019 the gains by Non-Majors seem to have stabilized. Furthermore, those gains seemed largely restricted to Spotify’s platform only. Apple Music has been less tumultuous in Mexico. It is worth noting that the stability on Apple might just be because that chart is younger and thus the platform missed out on the radical industry changes going on in 2018.

Comparing the trends on Spotify/Apple Music in Mexico is a little like a Rorschach Test for your own perspective on the music industry. That is, you can interpret it whatever way you want. There is not a singular, obvious story.

Mexico seems like it could go either way at this point: continue shifting in the favor of Non-Majors, or stabilizing with the Majors still in the favorable position. So what actually is going to come next? Our best bet is to look at other music markets and try to get some more context.

From Germany to Argentina: Indie Artists and Labels Are Making Major In-Roads

Germany

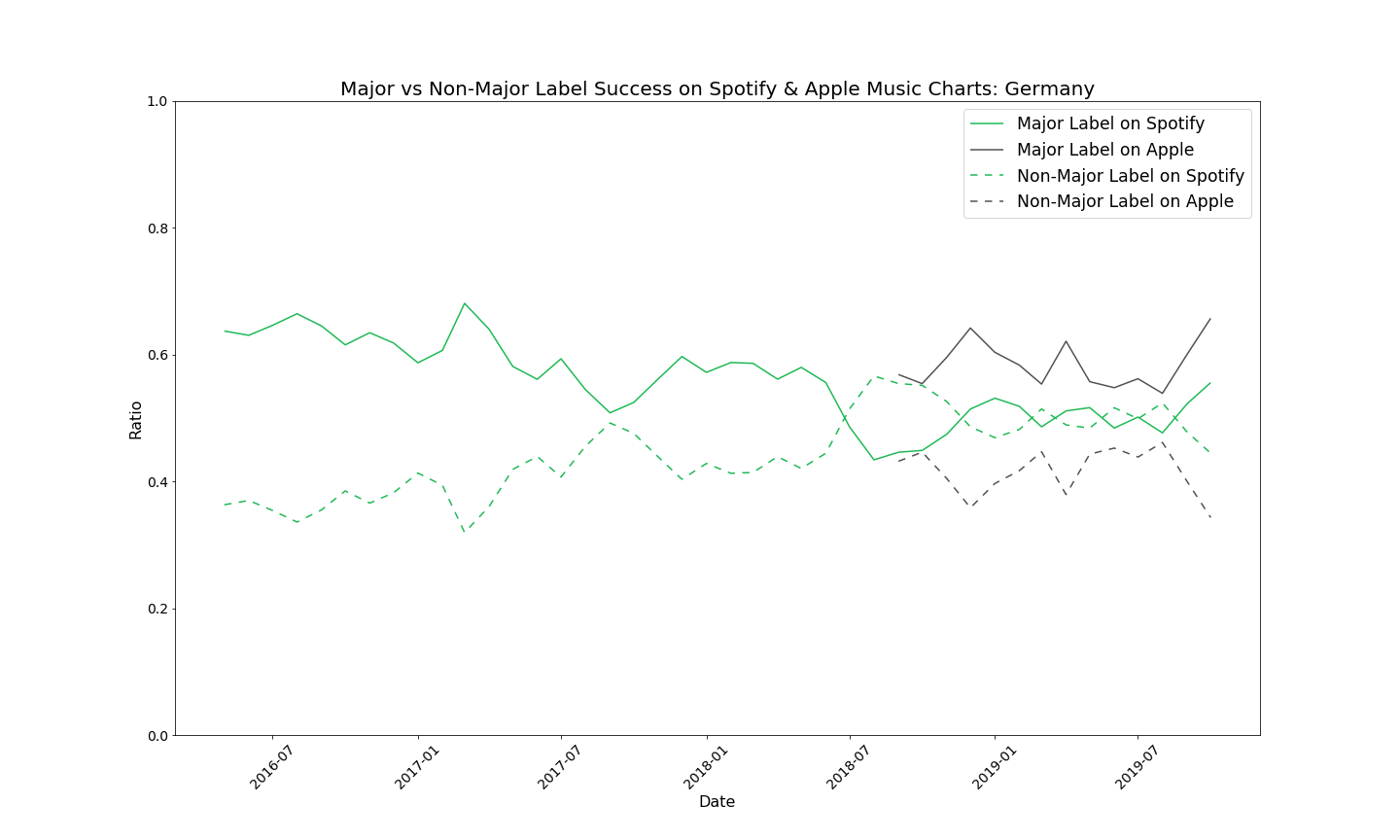

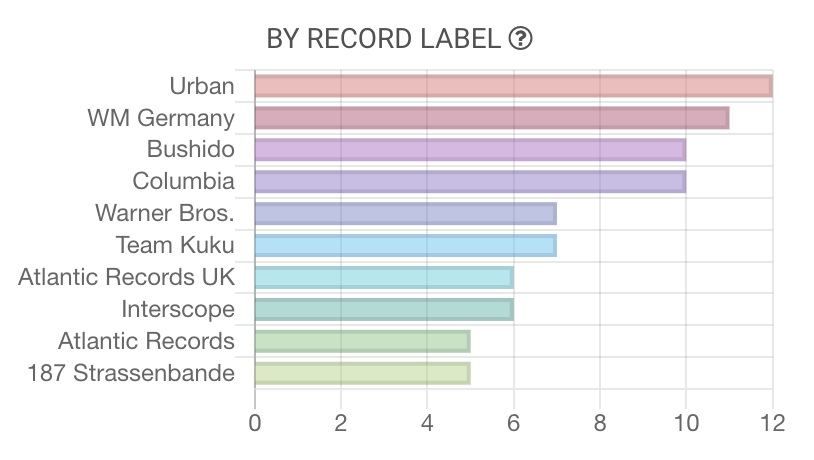

There are many markets where Non-Major labels are rolling up their sleeves and more than standing their ground versus the Majors. Currently, the most contentious arena we found is in Germany.

Compared to the global trends, the charts in Germany are much more evenly split between Majors and Non-Majors. On Spotify, there are even times when Non-Majors out-weigh Majors. Consistent with what we’ve already seen, listeners on Apple Music tend to favor artists on major labels compared to Spotify. However, Germany is the music market where the Apple Music ratio most closely becomes even.

Germany is the No. 4 music market in 2018, according to the IFPI, and one of the areas where Majors are most established, active, and dedicated. So, to see evidence of so much progress by Non-Majors there is quite staggering.

In one of the months where Non-Majors overtook Majors, the Majors still took the most slots on a label-by-label basis. But an increasing number of smaller organizations and artists combined together to end up turning the tide overall.

In Germany, Artists and labels such as RAF Camora, Capital Bra, Bushido, Team Kuku, AUF!KEINEN!FALL!, and JINX are able to climb onto the charts while engaging on projects that decline to officially sign with a major label.

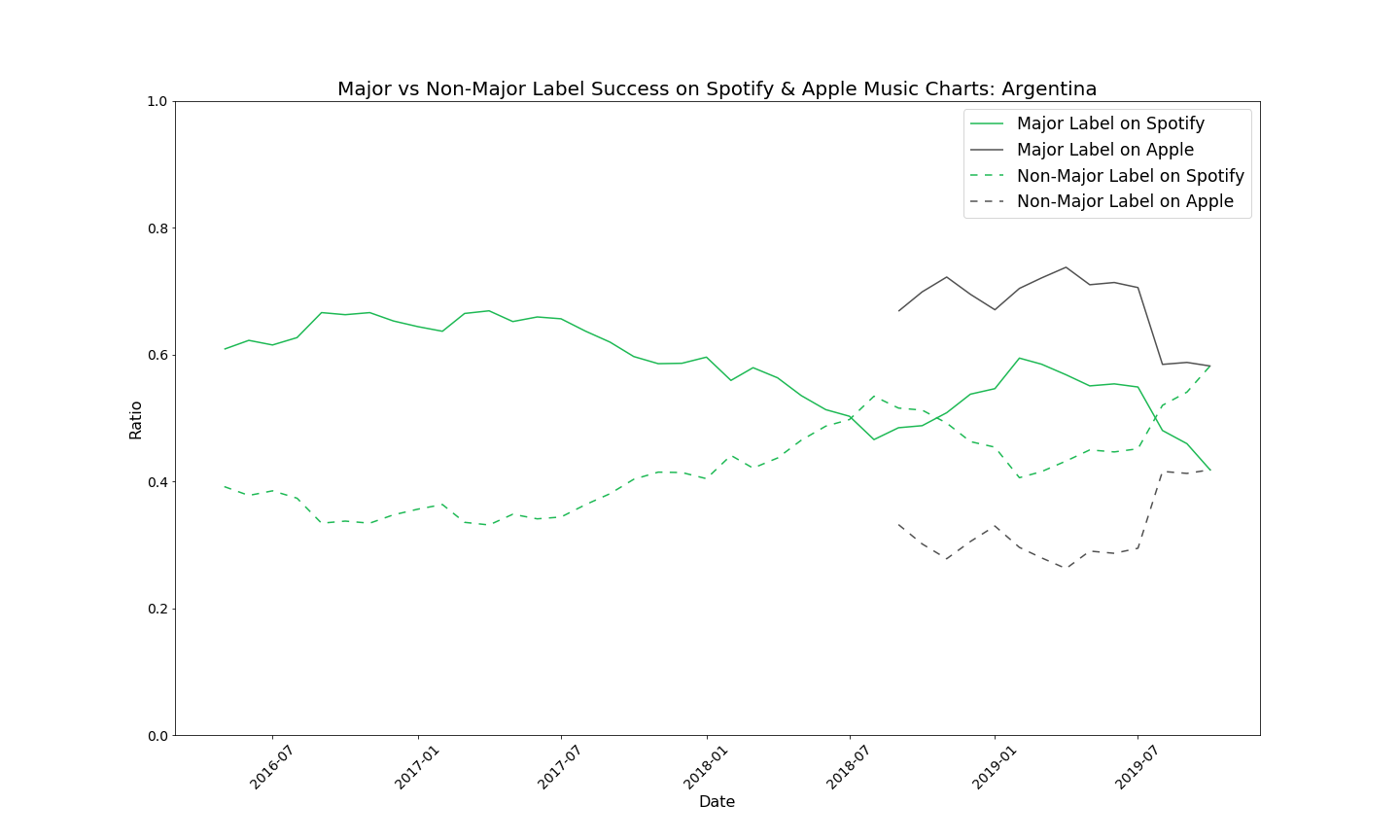

Argentina

Germany and Argentina are separated by an ocean, more than 7.6K miles (or 12K kilometers if you insist on using a measurement system that makes sense), and they have huge divergences in their chart-topping artists. Yet Argentina and Germany are both great places for artists looking to make a break outside of the confines of the major labels.

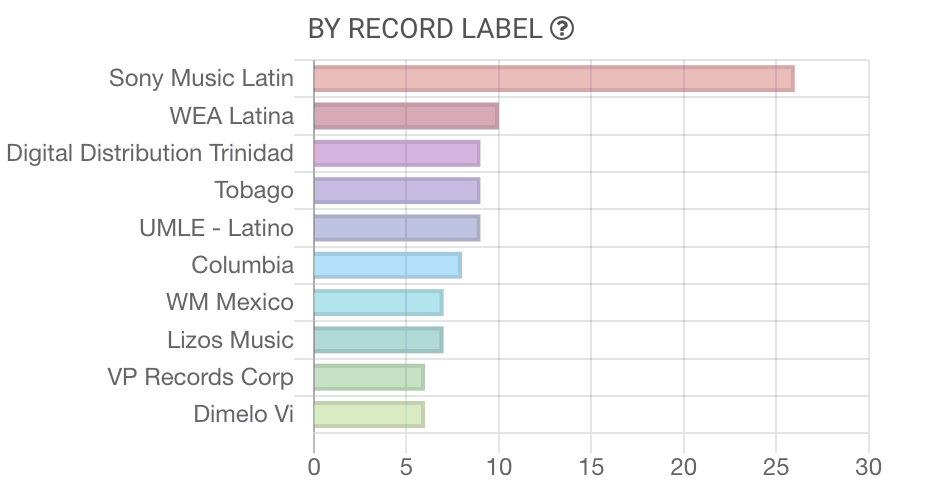

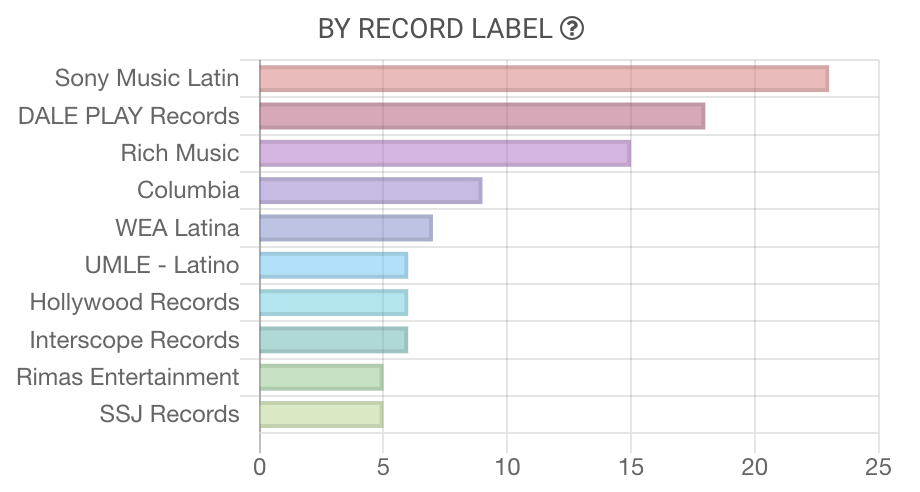

Argentina has similar trends to Germany. It is one of the markets where Majors and Non-Majors are most neck-and-neck. Non-Major artist Duki has made great strides with SSJ Records/DALE PLAY Records. Non-Major label Rich Music and Rimas Entertainment have deftly cut paths onto the charts by working with artists such as Bad Bunny and Anuel AA.

The back-and-forth trend visible in Argentina’s graph above reveals a fascinating insight into the music industry. Consider the Washington Post’s provocative declaration that, “Record labels said Latin Trap was ‘going nowhere.’ Billions of YouTube views proved them wrong.”

Well, okay, sure. The Majors maybe did not go all in on Latin Trap from the beginning, but that doesn’t mean that the opportunity to get into a hot music genre is gone. Latin Trap is not a bus that you did, or did not, catch; it’s a style to work within, a direction to channel your resources, skills, and craft.

And sure enough, the Majors are not throwing up their arms in frustration like the person I saw miss the morning train yesterday. They are more like the popular, older kid at the party who sees someone else is starting to be popular too. The Majors seem to have cast a detached glance over to big Latin Trap artists and said, “Oh hey, Latin Trap. That’s cool… Want to hang out with us?”

And successful Trap artists like A. CHAL are saying, “Me? Uh, yeah… sure!“

The back and forth trend on Spotify shows that this type of industry negotiation was not a one-time phenomenon, but is an on-going process.

The Majors Strike Back: Holding Ground in France and the United States

As the Latin Trap example in Argentina shows, the Majors are responsive and resilient. Just because they lost ground at one point doesn’t mean that they can’t adapt and reassert their value to artists.

There are a number of countries where we can see that major labels are holding their own very successfully. Take a look at France and the US – two of the most lucrative recorded music markets in the world.

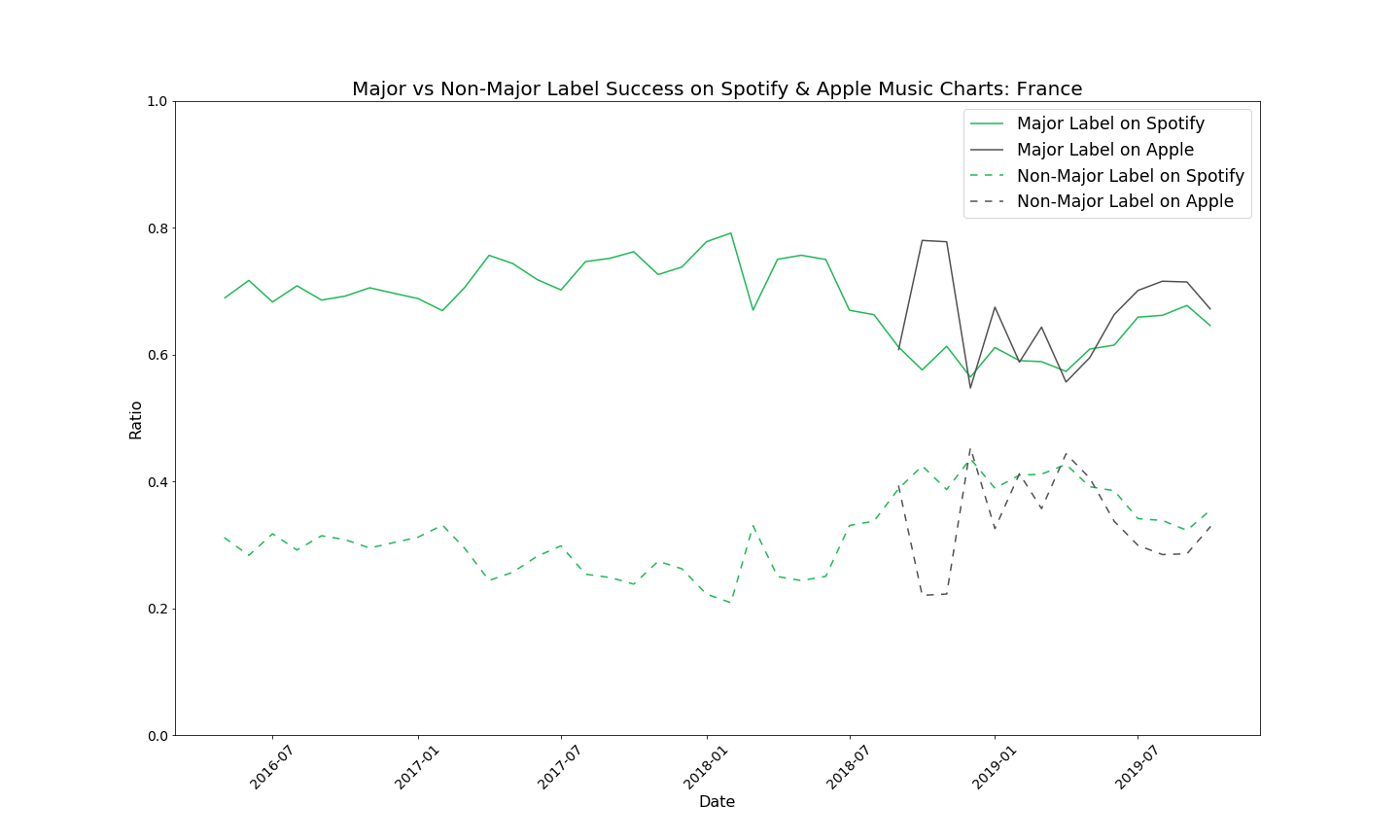

France

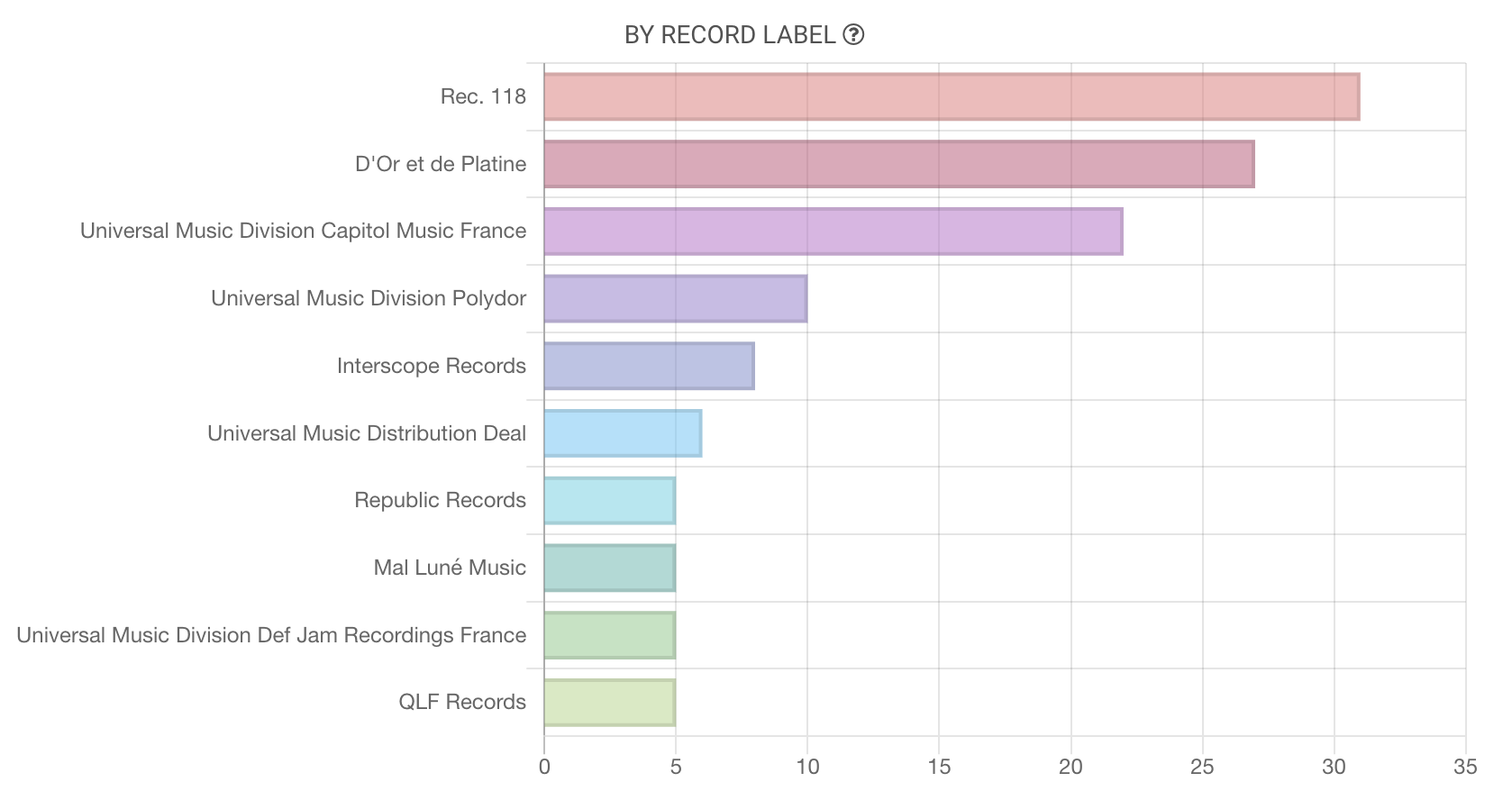

On the Non-Major side, Jul is holding on to a ton of chart positions with his own company D’Or et de Platine. PANENKA, QLF Records, and AllPoints are also quite successful. But even taken together, those are not enough to upset the Majors’ grip on the charts. Warner is the engine behind both Rec. 118 and Mal Luné Music, and unlike Argentina, there just aren’t enough other individual Non-Majors to compete.

In France, the 2018-crunch did hit the major labels but they have managed to rally themselves and are re-taking more chart slots.

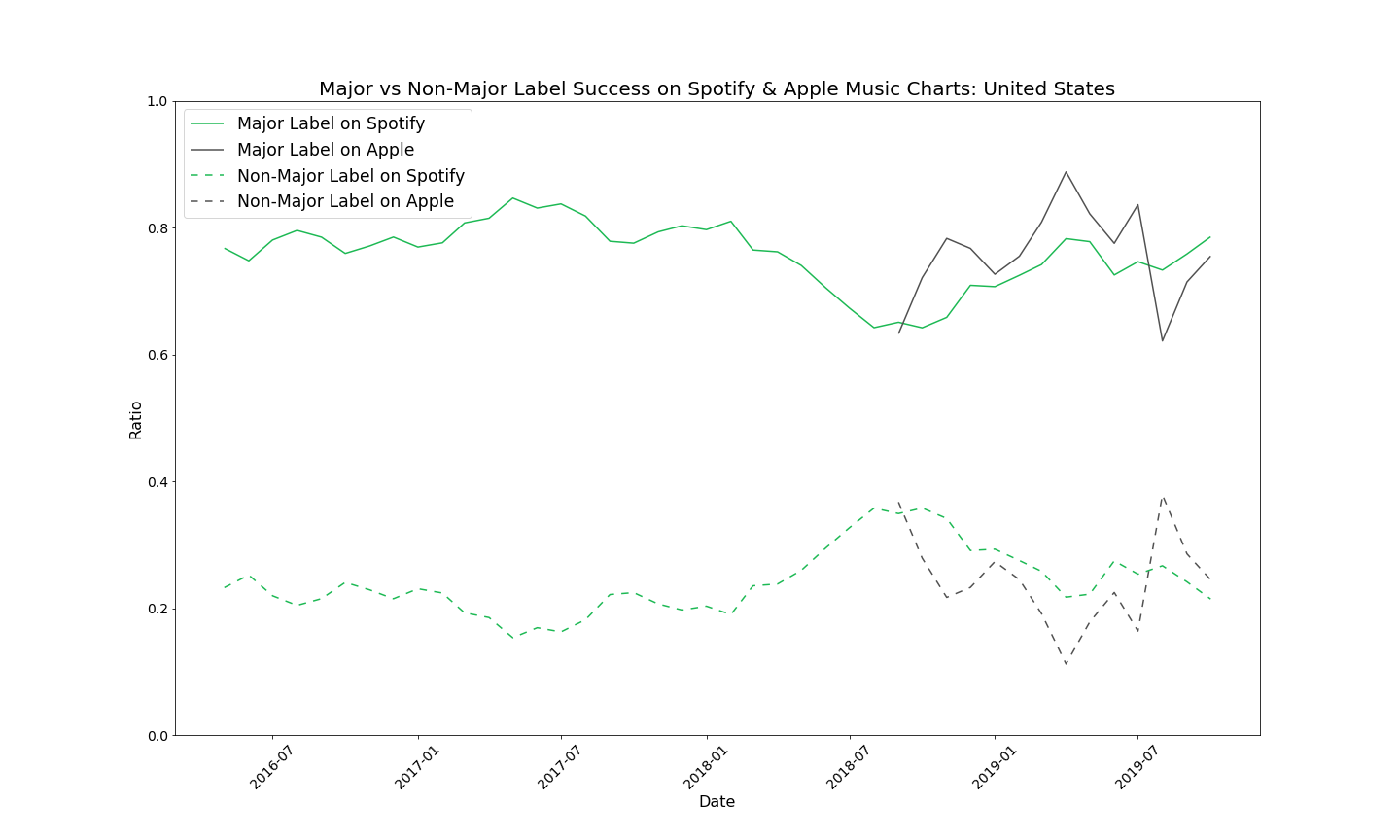

The United States

The American recorded music market makes the most revenue globally. That means it’s probably fair to say that it is also the music market where the Majors are dedicating the most resources and effort. It’s where they have the most to gain financially, and success stateside arguably garners cascading influence throughout the world.

So, how’d they fair over the past few years?

Like in France, Non-Major labels gained some serious ground starting around late-2017 to late 2018. However, the majors have resurged – perhaps absorbing some of their competitors. The balance of power has shifted, but not so much as to indicate that a completely new day were on the horizon.

This is the only market we saw where Non-Majors have outperformed on the Apple Music charts compared to their Spotify charts positions. Though it is probably worth mentioning for Spotify the U.S. chart is one of the lowest performances by Non-Majors across the globe.

So it may not be so much that Apple is more geared towards Non-Majors in the US, than majors just have the US market on lockdown–even on Spotify. It is fairly rare for Non-Majors to make grab one of the chart slots in the U.S. However, some artists and their labels like Kevin Gates/Bread Winners’ Association and YoungBoy Never Broke Again/Grade A Production still manage to break through.

Conclusion: The Majors’ Throne was Challenged but Intact…For Now

Speaking of YoungBoy NBA, he is a great example of the larger state of the industry and the relationship between Majors and Non-Majors. YoungBoy NBA is an artist who has released with Atlantic Records in the past but more recently has chart-toppers that are either 1) an independent release or 2) a collaboration alongside Juice WRLD that has exclusive licensing with Interscope. One cannot just ask whether a track by YoungBoy Never Broke Again is a “Major” or “Non-Major” release. It depends… and sometimes it can be complicated.

Anuel AA’s career is another microcosm of the blurring distinction between “Major” and “Non-Major.” Anuel AA is staying indie, but he has major collaborations with artists signed with Sony or Universal, and he distributes through The Orchard.

Anuel AA and YoungBoy Never Broke Again are just two examples among dozens, perhaps hundreds, of complex relationships between the Majors and artists creating their own unique business networks. The challenges of conducting this analysis are more than just a vexing analytical challenge, it is an insight into the shifting landscape of the music industry.

In the cases of collaborations between multiple artists, joint-deals, and distribution deals, the distinction between the two concepts of “Majors” and “Non-Majors” becomes fuzzy, at best. At worst, it ranges into misleading or even irrelevant.

Thinking beyond just chart-slots, and considering the monetization of music, the Majors have some solid strategies. Even when Non-Majors get momentum, they often end up distributing through a major label. Drake’s mega-album Scorpion was released through Young Money/Cash Money Records, but the exact relationship with that album, and those labels, to major record labels is…well, complicated. Universal receives distribution fees from Cash Money, cannot claim ownership, but can claim Cash Money as part of its empire in market share calculations. This unique relationship reflects a larger trend of Majors maintaining purse power even without rights ownership.

The streaming revolution may have changed how money is made in music, but it hasn’t revolutionized the chart territory held by the Majors. In the past few years, some Non-Majors have made big headway. Especially on Spotify, which seems to be a platform where listeners are more willing to embrace a wider range of music. But the gains by those artists are hard-won, and major labels are actively working to regain their control. But as the music landscape shifts and everyone is working to survive in a bold new music-world, more focus will likely need to be given to the myriad ways that artists and labels work together.

Methodology

All data for this analysis was drawn from the Chartmetric database. Chart-tracks were categorized programmatically based on the track meta-data and sub-string matching. Data accuracy was verified through numerous stages: manual review of the string mapping logic, manual review of the resulting categories by frequency count as well as by random sampling, and finally by randomly selecting combinations of chart/day/region and comparing the programmatic results to manual coding.

We conducted over-time analysis on 17 countries across a range of major music markets. We selected the countries that exhibited the general trends most clearly for presentation in this article.

We considered the Big Three to be the major labels Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment as well as any of their subsidiaries. For example, Interscope and Republic are counted as Universal. Atlantic and Spinnin’ are a part of Warner. Columbia and RCA are a part of Sony. Consequently, we counted any albums or singles released by any of these organizations was counted as a “Major” release.

We categorized any record label not openly affiliated with one of the three major labels into the “Non-Major” group. Some examples of independent labels are 300 Entertainment, Rich Music, VP Records Corp, Rimas Entertainment, and eOne Music. The majority of “Non-Major” record labels tend to be “Independent” labels that are smaller in size. However, some of the companies in this category are large corporations in themselves: Big Machine and Disney, for example, are considered “Non-Major” despite their formidable size and industry significance. We ran our analyses while excluding labels like Big Machine and Disney but the major trends between the Big Three and the rest of the industry did not change substantially.

If we found evidence of an album having a licensing deal or a joint-agreement with a major label, then we counted it as a release by a Major. However, we counted any album that had recording rights exclusively with a Non-Major and distribution rights with a Major as “Non-Major”.

You can click here to head back up to the start of the article.