Much has been written recently about how new music is being crowded out by older music. Radio guru Fred Jacobs digs deep into the problem and some possible solutions if anyone is brave enough to try.

By Fred Jacobs of Jacobs Media.

My recent blog post stirred up the expected conversation about the music industry and radio. Like the debates about guns, abortions, vaccines, and masks, everyone has an opinion. In fact, most of them are fervent.

The post focused around a opinion piece in The Atlantic penned by Ted Gioia, declaring – for all intents and purposes – that new music has seen better days. Gioia pulled data from different sources to make his point that the record labels have all but thrown in the towel on discovering new artists and groups, instead focusing on the green pastures of catalog music. [MORE: Is old new music REALLY crowding out new music?]

Some of you took exception to his analysis, pointing to everything from misreading the charts, how “new music” is categorized (18 months old or newer) to overemphasizing falling Grammy Award ratings.

I get it. I had some of the same visceral reactions to Gioin’s piece the first time I read it. And then I re-read it, and started thinking about the bizarre collaboration between the music industry and radio broadcasters to essentially do very little to expose the world to new music with the effort and force of past decades. Ironically over the past couple decades, consensus about anything between “radio and records” has been nonexistent. In fact, the two industries have been locked up in a Holy War over royalties and compensation to a point where they have each devalued the other’s contributions.

“to get behind new music is a bad model”

But the one thing they both apparently agree on is that to get behind new music is a bad model. As Gioia points out, the labels have done very little to discover “what’s next?” opting instead to focus on the profitability of vinyl, catalog sales, and recently publishing rights negotiated with some of the industry’s biggest and most successful artists.

Radio, in the meantime, once a true reflection of music and talk tastes that appealed to people from 12 years-old to death, has instead been playing it safe for decades, choosing to play the 25-54 game, the “sweet spot’ where most agency ad buys are centered. AM and FM radio stations were once the bastions of new music discovery, eager to expose and champion new music – and the teens and twentysomethings who couldn’t get enough of it. And in many cases, record companies and concert promoters supported these efforts with ad buys, promotions, interviews, and appearances.

“no single source of music exposure can truly carry the weight”

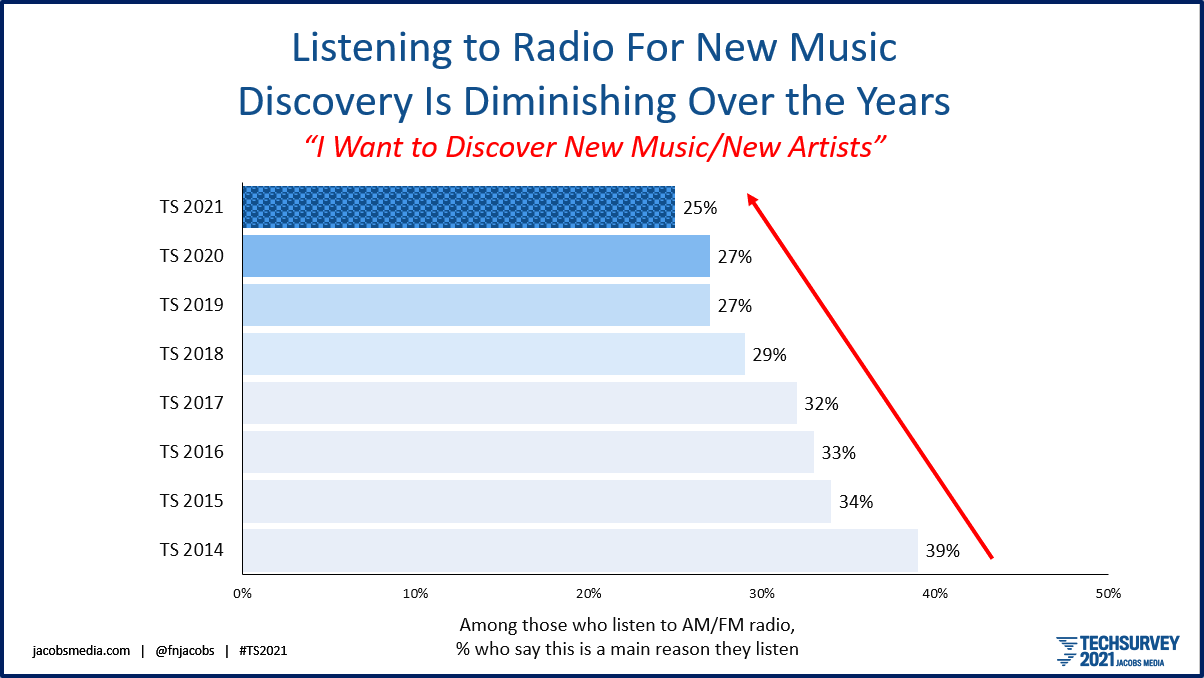

And the fruits of radio’s efforts to narrow its focus – or more to the point, its stagnation – has produced an odd effect where no single source of music exposure can truly carry the weight. We track the percentage of Techsurvey respondents who tell us a main reason they listen to broadcast radio is to discover new music and new artists. Like many of Gioia’s charts, it tells a story:

Yes, our sample is comprised primarily of radio fans. And yes, they are aging. But the trajectory here is unmistakable. Broadcast radio has many great qualities and discernable assets. Unfortunately, playing and exposing new music is rapidly becoming a non-factor in the platform’s appeal. Radio has abdicated that role, and has seemingly little desire to win it back.

As I was writing yesterday’s post (on Monday), a tweet came flying in from Abbey Minke, a radio personality in St. Cloud, Minnesota. And it lit up my Twitter feed:

it spurred a long discussion about drawing the lines of nostalgia – where they begin and where they end, what IS classic?, and when and if the 2000s will spur a new format aimed at those who grew up 20 years ago, ready to enjoy the music they grew up with. Others talked about a theme Ted Gioia addressed as well – the quality of new music coming out today.

Abbey, a challenge with architecting a new radio format that focuses on that decade circles back to the highly fragmented ways in which Millennials were exposed to that music in the first place. If you’re a Millennial, you grew up with iPods, video games, Pandora and Spotify, TV and movie soundtracks, and untold other sources of music. And yes, radio, too.

In the aughts, as it is today, everyone’s experience with new music was unique. Building a 2000’s-era music format designed to cater to a broad coalition of fans is fraught with challenges. In retrospect, creating formats like Oldies and Classic Rock was relatively easy because everyone’s first exposure to the music from those respective eras and genres was the same – on the radio.

“Today’s means of discovering new music is splintered into hundreds of media points”

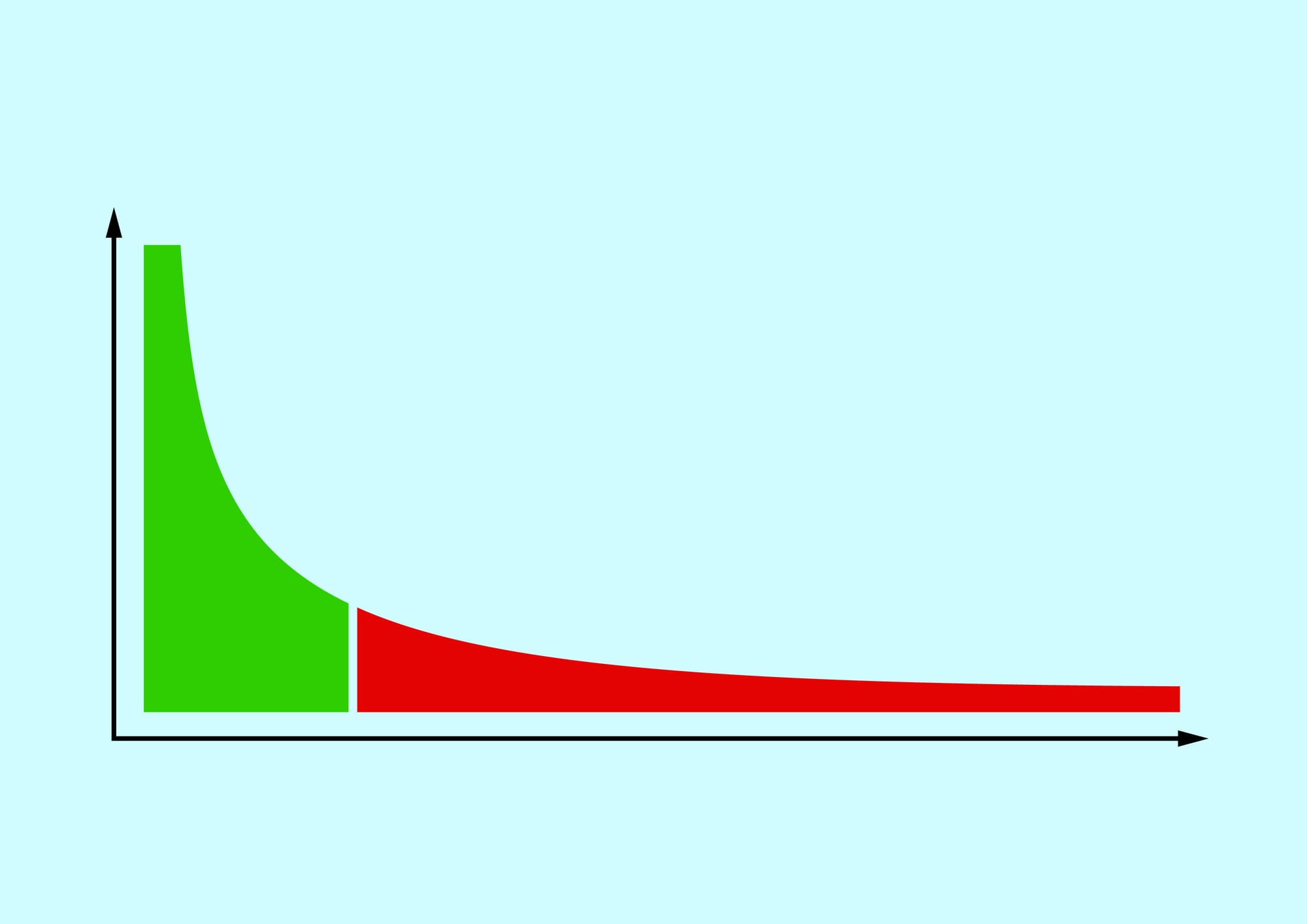

Today’s means of discovering new music is splintered into hundreds of media points – a long tail of outlets where one can hear any variation of new music. And none of these has an audience “mass” enough to truly shape tastes – like radio did.

It’s the story of “the long tail,” a concept developed and defined by Wired’s Chris Anderson nearly two decades ago that explains, in large part, why our music world is devoid of big, mass appeal hits. Come to think of it, with the exception of anomalies like the Super Bowl, smash successes in the worlds of movies, TV shows, books, and other cultural outlets are few and far between. Even though the population has grown and media access has exponentially improved, we’re all watching and listening to different stuff. Better put, we are our own programmers – and distributors.

Here’s how Anderson put it back in 2004:

“Up until now, the focus has been on dozens of markets of millions, instead of millions of markets of dozens.”

Yes, that’s AM/FM radio in green: a lot of exposure for a finite number of songs, heard again and again on hundreds (and even thousands) of radio stations. That’s how you “make” hits – playing great songs with force and yes, repetition. And when those songs are played on multiple outlets in a metro – and eventually, in cities and towns all over the country – you have smash hits.

And then there’s red part, the “long tail” of today – a splintered environment of music of eclecticism and personalization across numerous outlets, gadgets, and platforms. The proliferation of radio stations across all those outlets has democratized music, while diluting to a point where big hits are few and far between.

In his Atlantic article, Gioia expresses the hope that when “the next big thing” comes along, we’ll know it. But that’s like waiting to win the lottery. And while artists the caliber of Sinatra, Elvis, the Beatles, and Michael Jackson may never come along again (I don’t believe that, by the way), responses to Abbey’s tweet and yesterday’s post suggest many of you believe great new music is “out there.”

And that’s why I end up back where we started from – radio. In Gioia’s analysis, he is generally dismissive of radio, describing it as only a small part of the problem:

“Radio stations are contributing to the stagnation, putting fewer new songs into their rotation, or – judging by the offerings on my satellite-radio lineup—completely ignoring new music in favor of old hits.”

Technology may have changed the way we discover new music (or don’t), but radio has been an active co-conspirator by failing to wave the new music flag. Like in Ted Gioia’s essay, most music observers write off radio as a medium of the past that “no one listens to today.”

But the fact is, radio is the last mass reach audio platform left. For all the gains amassed over the past decade or so by SiriusXM and Spotify, their “cumes” are still dwarfed by radio. And even if they were able to engineer a growth spurt, they are, by definition, fragmented to begin with – hundreds of channels, millions of playlists – the long tail.

I am often asked why Classic Rock worked. And while the planets lined up perfectly in the early 80’s when I was launching the format, America was ready to hear music from the 60’s and 70’s. When WMMQ in Lansing hit the airwaves 37 years ago this spring, the radio airwaves were loaded with “Hot Hits” – new music in rock, pop, and other genres. MTV had recently debuted, putting the focus on new and now.

When the pop culture world gravitates to one end of the spectrum, there is often a lot of shares available on the other end of the spectrum. That was the audience “real estate” Classic Rock quickly captured. And in typical radio fashion, success in one market always spawns imitation and duplication in other places. By the end of 1986, there were Classic Rock stations in D.C., Boston, Atlanta, L.A., Detroit, Chicago, and many other cities and towns all over the U.S.

I’m a believer a radio company dedicated to trying something different with a perennial loser could launch a new station that plays nothing but new music. I don’t know what this station would sound like, but it could take advantage of the crowd-sourced, voting, and exposure elements that are now easily accessible parts of the digital took kit. It would have to have a strong video component, maybe a concurrent stream.

I do know it wouldn’t be programmed by a bunch of old radio souls, but should clearly be the province of a new generation of programmers – just like many of us where back in the 70’s and 80’s.

Could a radio station today ever be as influential today as KHJ, CKLW, WMMS, or WBCN were “back in the day?”

Not a chance. Too much of the media landscape has changed – forever.

But in a world where consumers are looking for something new to embrace and radios are still front and center in most cars, radio still has a voice. The question is, does it have anything left to say?

For those of you scoffing at the idea that radio could be an integral part of the solution, think about the assent and resurrection of vinyl – another old, tired music format that has achieved new levels of popularity – especially among younger generations unaware of terms like “B-sides” or “cue burn.”

Of course, this requires an owner ready to try something unique, different enough to capture attention and generate some buzz. It must be a broadcaster who still believes in the power of radio as an influential, taste-making medium, and not just a megaphone to drive ears to podcasts and landing pages. And it would, by definition, just play new stuff, without fear of alienating “the adult demos.”

Could it happen?

Is there anyone bold enough to design and launch a radio spaceship in 2022 that could go the distance?

Is there enough great new music out there to power this experiment?

And will there be sufficient audience in our A.D.D. world to even give it a listen?

Would the music industry step up and support it?

Just like “the next big thing” in music, the “next big thing” in radio won’t sound like a radio station we’ve already heard.

That’s OK.

We’re all tired of the same old thing.

MORE: Is old new music REALLY crowding out new music? [Fred Jacobs]

Fred Jacobs founded Jacobs Media in 1983, and quickly became known for the creation of the Classic Rock radio format. Jacobs Media has consistently walked the walk in the digital space, providing insights and guidance through its well-read national Techsurveys. In 2008, jacapps was launched – a mobile apps company that has designed and built more than 1,300 apps for both the Apple and Android platforms. In 2013, the DASH Conference was created – a mashup of radio and automotive, designed to foster better understanding of the “connected car” and its impact. Along with providing the creative and intellectual direction for the company, Fred consults many of Jacobs Media’s commercial and public radio clients, in addition to media brands looking to thrive in the rapidly changing tech environment. Fred was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2018.