________________________________

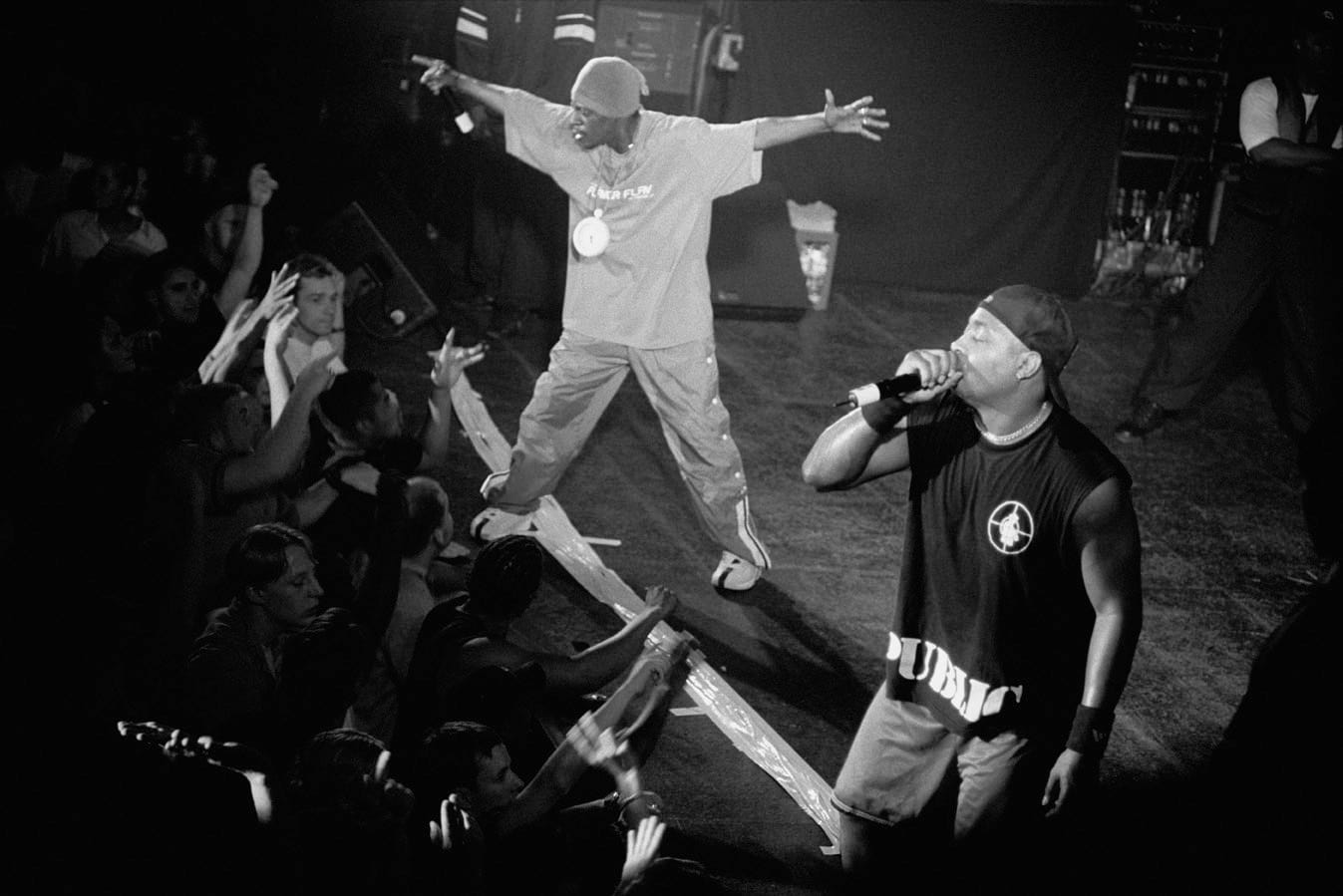

Guest post by Charlotte Yates of Soundfly's FlypaperIn 1990, I had the honor of meeting Chuck D after Public Enemy’s first performance in Wellington. He was tired and jet-lagged but gracious enough to shake hands and chat for a microsecond. It was a privilege to directly congratulate him on the hip-hop group’s groundbreaking second album from 1988, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.Hang on… groundbreaking? I thought debut albums were supposed to “break ground,” and don’t second albums generally end up being career-stalling crowd disappointments? Many times yes; it happens so often in fact that people tend to refer to this phenomenon as “Second Album Syndrome” (SAS).So if SAS is definitely a thing, how do some groups manage to avoid it while others succumb to it?The good thing is that if your first album went relatively unnoticed, you’re not in too much danger for releasing a disappointing second. But artists whose debut albums were met with wide praise and excitement have a slightly harder time. The generally accepted scenario is that you have your entire life to make your hugely successful first album, but only a short couple of years to release your follow-up. But why is this so complicated?Well, the more attention your debut album gets, the more jam-packed your schedule gets; with touring in support of the music and endless promotional demands. The resultant extreme change in lifestyle, combined with pressure from your audience and your industry contacts means that you’re expected to deliver an “as-good-if-not-better” sophomore album, very quickly. And those ingredients tend to cook up a boiling stew of flop. But let’s flip back to Public Enemy for a moment, because how they managed to concoct their sophomore album is worth taking a closer look at!Here’s some insight from the executive producer of It Takes a Nation, Rick Rubin.“At the time Public Enemy came out, they were the least successful group on Def Jam… It wasn’t until the second album when people started accepting him [Chuck D] and got used to it. It was just so radical at first that when people heard it, they didn’t want that. Nation was important in that Public Enemy was the first group to really talk about serious political stuff… They really stepped up, but with that said, I really loved their first album too… But there’s a reference on the second album where Chuck says, ‘Last time you played the music, this time you play the lyrics.'”There are a number of strands at work here including clarity of vision and strength of purpose. Public Enemy had something to say — from day one actually, but by the second album they had learned how to say it. Album two wasn’t just a release for the sake of releasing something, it was a statement unto itself that needed a record to be its envelope. And it was a crank-up.Speaking of the envelope, Public Enemy also changed the way that vision was delivered too. Rubin describes Chuck D’s approach:“He’s like, ‘I’m willing to do it under these terms: It’s called Public Enemy. It’s a group. It’s more like the Clash than a rap group, and it’s me and Flavor Flav, and [Prof] Griff and Hank [Shocklee] are involved.’ And I said, ‘Whatever you want to do is fine.'”Once the message and style of material were clear, the team was eventually solidified. The addition of Rick Rubin as executive producer and the Bomb Squad “edge-of-panic” production team who knitted sirens, squeals, funk, and quirk with Chuck D’s polemic fused lyrics meant all were swimming in one stream. Making new work in this stage means being open to collaborators of equal, but different strengths who can realize an overarching style and vision, supported by experimentation and innovation in the studio.

- Nirvana – Nevermind

- Van Morrison – Astral Weeks

- TLC – CrazySexyCool

- Joni Mitchell – Clouds

- Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

- Anita Baker – Rapture

- Lou Reed – Transformer

- Simon & Garfunkel – Sounds of Silence

- The Pogues – Rum, Sodomy and the Lash

- Rickie Lee Jones – Pirates