_______________________________

Guest post by Cherie Hu from Forbes.comIf you are a diehard music fan—spending $120 a year on a streaming service with access to millions of songs, $100 a year on live shows, or $60 on a single sweatshirt emblazoned with the face of your favorite artist—you are arguably a vanity investor. Your primary motive in shelling out your hard-earned money for Spotify, a Coachella ticket or a Chance the Rapper sweater isn’t to make a profit, but rather to attach your name to a particular brand, scene or aesthetic, regardless of its financial viability."what if your spending on music became an investment in the traditional sense…"

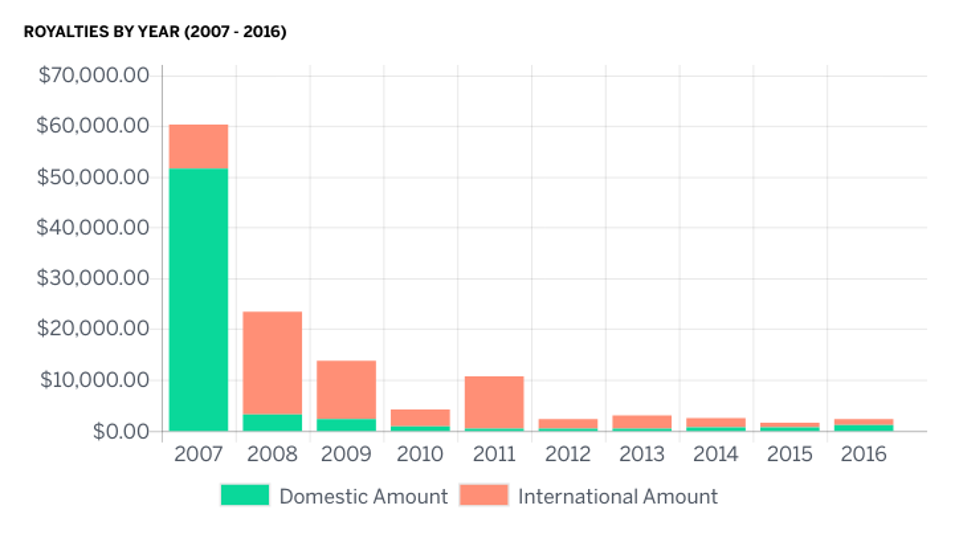

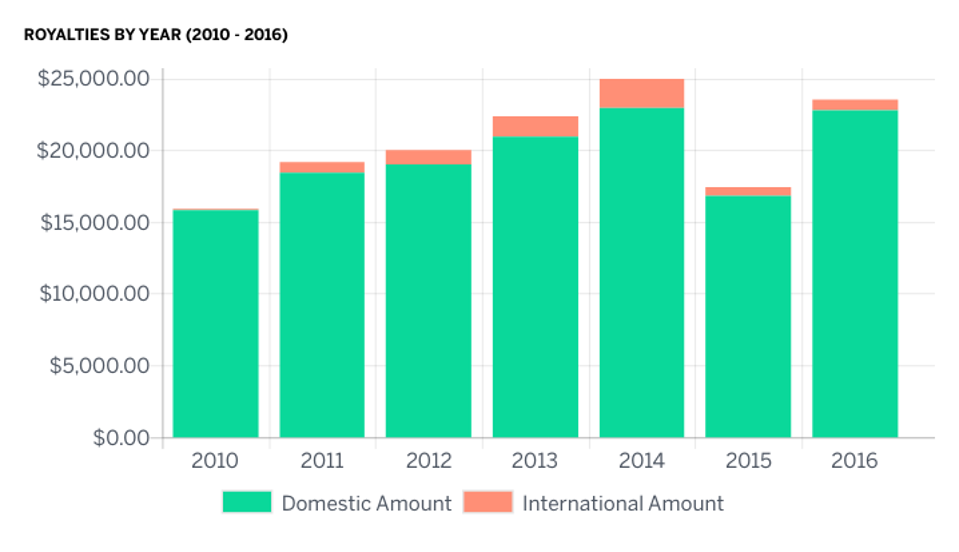

But what if your spending on music became an investment in the traditional sense: putting money into artists’ careers with the deliberate intention of receiving returns on their royalties and other revenue streams? Record labels already build their entire business models around this premise, but what if you could do the same as an average fan? Would it still be an act of vanity? More importantly, would it actually make you any money?Historically, the music business and the financial community have not been comfortable partners. Creativity happens on its own timeline, and is difficult to align with a system that expects consistent returns. Yet, an increasing number of financial firms are forming alternative investment funds that frame independent and emerging artists as the next lucrative asset class, such as BlackRock’s Alignment Artist Capital and AGI Partners’ Unison Fund. As paid streaming subscriptions continue to drive aggregate growth in recorded music revenues, industry insiders are cashing in specifically on performance royalties, which are paid to songwriters and composers every time their work is “broadcast” in public (including on streaming services). Within the music industry, publishers like Concord Music Group and Round Hill Music are acquiring legacy catalogs for unprecedented, multimillion-dollar prices. According to Billboard, a songwriter’s catalog typically sells for 10 times its net publishing share (NPS), but that multiple has increased to 12x or even 16x in recent years amidst a seller’s market.IPOs For Song RoyaltiesIn response, some companies are even trying to launch IPOs for song royalties. The Hipgnosis Songs Fund, a music IP investment company co-founded by veteran artist manager Merck Mercuriadis (previous clients include Iron Maiden, Elton John, Macy Gray and Mary J. Blige), is planning a £200 million listing on the London Stock Exchange later this year. Music production duo F.B.T. Productions is selling off up to 25 percent of their royalty share from rapper Eminem’s pre-2013 catalog, and online royalty marketplace Royalty Exchange is helping to raise anywhere from US$11 million to $50 million to list the income stream directly to NASDAQ, under the moniker Royalty Flow. Notably, Royalty Exchange is leveraging Regulation A+ of the JOBS Act for an equity campaign in which any private investor, accredited or otherwise, can participate, with a minimum buy-in of $2,250 for 150 shares of Class A common stock.Interestingly, however, Hipgnosis and Royalty Exchange are making fundamentally contradictory arguments for why you should invest in music royalties. Hipgnosis’ intention-to-float filing with the LSE claims that royalties generate attractive returns because they are “driven by consumer spending and listening habits which are uncorrelated to capital markets.” In other words, songs are evergreen investments and, with streaming, their earnings potential now spans decades rather than years.In contrast, Royalty Exchange is relying heavily on capital market trends to validate its business. The company’s investor deck and Facebook ads cite Goldman Sachs’ recent report that paid music streaming revenue will grow 833% by 2030 (a projection that industry insiders have already criticized as inaccurate and self-serving). “After a 15-year-slump, the introduction of streaming is giving the music industry new life” and “directly benefiting royalty owners,” reads one Royalty Exchange ad on Facebook. “We believe the music industry is on the verge of a massive bull market – Invest in Royalty Flow Today,” reads another.There is some validity to Royalty Exchange’s stance. As Spotify itself plans to go public this quarter, and as smart devices like the Amazon Echo become more instrumental in music discovery, the music business will be clinging tightly onto tech stock performance like never before. Plus, two of the three major record labels are subsidiaries of publicly-traded corporations (Universal Music Group under Vivendi, and Sony Music Entertainment under Sony Corporation; Warner Music Group is owned by private holding company Access Industries).But there is also a serious false equivalency at play here: buying Spotify stocks is not the same thing as buying stocks of songs that happen to be available on Spotify. While streaming is the dominant form of music consumption, music is still largely a copyright business at the end of the day, which thrives on active pursuit of licensing opportunities, not on passive observation of the public markets.What’s more, both Hipgnosis and Royalty Exchange are fully transparent about the risks of investing in music IP. The Hipgnosis prospectus claims that songs are difficult to price because “the valuation method is inherently retrospective, in an industry which is undergoing rapid change affecting future revenues.” Despite all the hype, Royalty Exchange also warns on its website that investment in the Royalty Flow IPO “will be suitable only for persons who can afford to lose their entire investment.”All of this sends a mixed message that should make any investor wary.TECHNOLOGY HAS DEMOCRATIZED MUSIC INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES…Beyond music, entrepreneurs in industries ranging from sports to food & beverage and precious metals have tried to launch their own royalty marketplaces and IPOs, all touting the same benefits such as greater diversification for investors and the opportunity for fans to own a stake in their favorite brands or athletes. Most of these projects, however, have failed to deliver on their promises. In fact, one of the most highly-funded such projects—athlete stock exchange Fantex, which raised over $70 million across multiple funding rounds from investors including Duncan Niederauer, the former head of the New York Stock Exchange—shut down in April 2017 due to low trading volumes.But that hasn’t stopped similar founders from tackling the music industry in droves. Interestingly, most of these founders are trying to translate the vanity investment of music fandom into cryptocurrency—such as Vezt, which launched an Initial Song Offering (ISO) for royalties from Drake’s “Jodeci Freestyle” on the Ethereum blockchain; Choon, which aims to tokenize the entire music streaming and discovery experience; and startups like Ujo Music, Fanmob and SingularDTV that are working to tokenize the artists themselves.Royalty Exchange has not integrated any cryptocurrency capabilities into its platform, focusing instead on an overall streamlining of the royalty-selling process for both investors and artists. “Most of the artists we work with are actually the ones behind the major performing acts,” Matt Smith, CEO of Royalty Exchange, told me. “There are hundreds of thousands of different creators in an ecosystem who support an A-list artist, but who might not have the same financing and capital-raising options that the latter might have.”If these companies are claiming that royalties are so valuable, though, why should rights owners even sell? The reality is that many artists, especially in indie and DIY communities, are constantly strapped for cash to purchase new equipment or software, finance tours, film music videos, or engage in any other project that might advance their careers. Royalty Exchange aims to help these artists use their older work to fund new ventures, through a more flexible arrangement than a traditional publishing or label contract.“Having enormous value in the long run doesn’t preclude you from a disproportionate amount of cash having a significant impact on your life today,” said Smith. “If you get $50,000 today, that might empower you to avoid a bad publishing deal in which you would otherwise need to promise to deliver a body of work over a certain period of time. None of our deals involve that—we have nothing to do with the typical ‘go-forward’ agreements in publishing contracts. We’re only looking at partial, passive interest in back catalog, not at controlling stakes in future copyrights.”“As someone who’s spent 35 years working as an artist advocate, I’m very cognizant of the fact that buying writers’ or artists’ assets may be incongruous with artist advocacy,” Mercuriadis told me ahead of his talk at FastForward London in September. “But I’m very clear about what I’m buying, and I’m also making it clear that people shouldn’t sell, because I believe these assets will triple in value over the next several years. The only reason you should sell [to Hipgnosis] is if you think a $20- to $40-million check makes such a difference in your career right now that it’s worth giving up that potential upside.”…BUT IN THE STREAMING ERA, NOT ALL MUSIC IS CREATED EQUALSo we have this incredible opportunity for artists to receive no-strings-attached advances on future royalties, but is there anything beneficial for the investor? Mercuriadis thinks so—arguing that the music industry's current financial inflection point is unrepeatable, and that those who invest in royalties today will see unparalleled returns further down the line. “The assets are always going to be great investments, and they’re always going to spit out that predictable reliable income,” he told me. “But you’re never going to see another opportunity to buy them at these kinds of prices.”Yet, not all music catalogs perform equally well in the age of streaming—and, ironically, the best proof for this argument lies in the myriad of data available on Royalty Exchange. Every single auction listing on the platform comes with an historical, granular earnings report, shining a fascinating window into what types of music catalogs might generate more reliable revenue than others in the streaming age.For instance, songwriter Anthony Keith Lawson recently sold 100% of his share of public performance royalties from Akon's 2006 hit single "Don't Matter" on Royalty Exchange. Lawson’s share generated $2,302 in royalties over the previous 12 months, and the winning bid came in at $28,000—a bullish 12x multiple. Yet, the revenue that Lawson’s share generated over the past several years actually paints far from the continued, predictable, sustained picture that investors typically want to see: